|

Posted 11/29/23

WARNING: (FRAIL) HUMANS AT WORK

Amid chaos and uncertainty, the presence of a gun can prove lethal

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Adrian Abelar concedes that he had a pistol in hand when he stepped out of his vehicle on that fateful day in September 2021. But his lawsuit against the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department insists that his intentions were actually benign:

As plaintiff complied with Deputy 1’s direction to exit, he discarded a handgun, tossing it away from himself and the Mazda. (pg. 4)

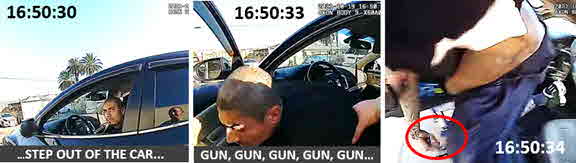

Alas, that’s definitely not how the deputies saw it. According to the video compilation posted by the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, Deputy #1 ordered Abelar out of the car. And when he saw that the man had a gun in hand, the deputy frantically (and repeatedly) yelled “gun!”:

Deputy #1 and his partner (Deputy #2) instantly wrestled Abelar to the ground. Deputy #3 (identified by the Sheriff and in the lawsuit as Deputy Yen Liu) then fired once. Discharged about six seconds after Deputy #1 yelled “gun”, her bullet struck Abelar, who was lying on his stomach, in the back. Thankfully, the wound wasn’t fatal.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Should Deputy Liu have fired? We’ll come to that later. First, let’s explore what brought the deputies to the auto body shop where the encounter took place. According to the Sheriff’s video compilation and “transparency summary”, the shop’s owner had telephoned the sheriff’s station to report that a man, later identified as Abelar, brought in his car and demanded it be promptly repaired because he was wanted for murder:

…Alright, I got a body shop. I got a guy on my property who’s telling me fix his car right away because he’s up for attempted murder, and the cops are chasing him all over the neighborhood. He just pulled into the back of my shop a half hour ago, needs wheel bearings and I just want him out of here because I just had a “Redacted”, and so if you guys could just roll by he’s in a 2009 Black Mazda 4-door, he’s about 6-2, about 110 pounds, very very light skin with a tank top his girlfriend is in his car; get them off my property please…

The deputies’ response was delayed, and the shop owner called back to complain. When the badge-wearers finally arrived, they found Abelar and his girlfriend seated in a car that was clearly undergoing repairs. Its left front wheel was gone and the front end was jacked up.

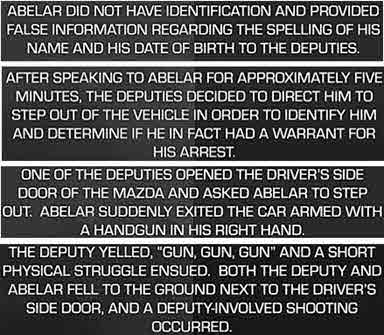

Deputy #1 spoke with Abelar. During their interaction, which  went on for about five minutes, Abelar was evasive throughout. He purposely misspelled his last name (“v” instead of “b”), furnished an incorrect birth-date, and falsely asserted that the shop had his driver license. That caused a brief delay as deputies confirmed that no, it didn’t. went on for about five minutes, Abelar was evasive throughout. He purposely misspelled his last name (“v” instead of “b”), furnished an incorrect birth-date, and falsely asserted that the shop had his driver license. That caused a brief delay as deputies confirmed that no, it didn’t.

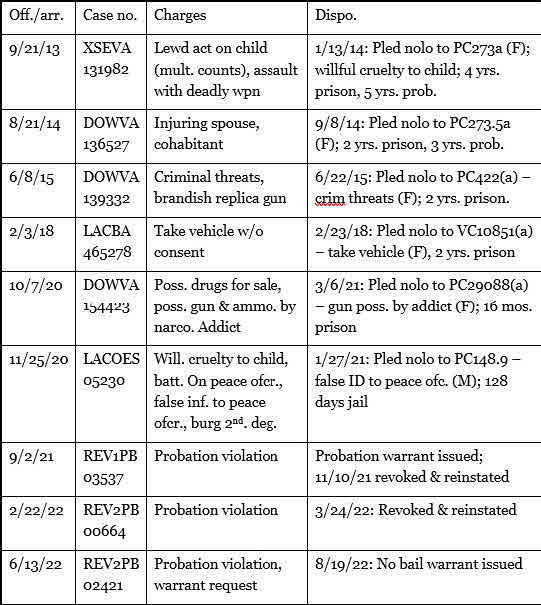

Why was Abelar deceptive? Here’s a summary of his Los Angeles Superior Court cases, which we gathered through a paid online search:

Abelar was a convicted felon. His 2014 conviction for felony child cruelty would prohibit his possession of a firearm. Six years later he was convicted of gun possession by an addict. And while he wasn’t wanted for “murder,” he was wanted for violating the term of probation that was imposed after a 2020 conviction for furnishing false ID to police. Abelar was a convicted felon. His 2014 conviction for felony child cruelty would prohibit his possession of a firearm. Six years later he was convicted of gun possession by an addict. And while he wasn’t wanted for “murder,” he was wanted for violating the term of probation that was imposed after a 2020 conviction for furnishing false ID to police.

During Abelar’s most recent tangle, the three deputies who responded didn’t know who Abelar really was, nor that he was armed with the pistol depicted above until it was literally too late. Their subject’s deceptive demeanor, though, seemed clear from the start. Here’s how the Sheriff’s video set out the initial five-minute encounter:

At the end of those five minutes, Deputy #1 ordered Abelar out of the car. As Abelar began to exit, the deputy realized that the man was gripping a gun in his lowered right hand. Deputy #1 instantly began yelling “gun!” and took Abelar to the ground. Deputy #2 jumped in to help. During this process, which took all of five seconds, Abelar’s pistol fell away. Deputy #3, however, was a few steps off. She may have never seen the gun. But what she knew for sure was what Deputy #1’s “gun, gun, gun” alert forcefully conveyed six seconds earlier: that deceitful, violent man who told the body shop owner that he was wanted for murder was armed. At the end of those five minutes, Deputy #1 ordered Abelar out of the car. As Abelar began to exit, the deputy realized that the man was gripping a gun in his lowered right hand. Deputy #1 instantly began yelling “gun!” and took Abelar to the ground. Deputy #2 jumped in to help. During this process, which took all of five seconds, Abelar’s pistol fell away. Deputy #3, however, was a few steps off. She may have never seen the gun. But what she knew for sure was what Deputy #1’s “gun, gun, gun” alert forcefully conveyed six seconds earlier: that deceitful, violent man who told the body shop owner that he was wanted for murder was armed.

If so, would her ostensibly defensible reason for shooting Abelar overcome the fact that he had, seconds earlier, been disarmed?

Adrian Abelar survived his wound. Alas, uses of force gone astray often prove needlessly lethal. An instance that stands out for its tactical complexity is the 2020 killing of Breonna Taylor by Louisville police officers who were serving a no-knock search warrant at the apartment she shared with her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker. As it turns out, the warrant was, evidence-wise, deeply flawed. But our attention here is on the situation officers encountered when, seconds after making entry, they were fired on by Mr. Walker, who said he thought they were intruders. His bullet struck an officer in the leg. Police unleashed a barrage of return fire. Their shots missed Mr. Walker but fatally wounded Ms. Taylor, who was unarmed but had appeared alongside him. Shots fired by Detective Brett Hankinson entered an adjoining apartment. Although they struck no one, he wound up being the only officer prosecuted in this case.

As one might expect, ordinary citizens were stymied by the unforgiving circumstances that Detective Hankinson and his colleagues had faced. Hankinson was acquitted of state endangerment charges, and his Federal trial for civil rights violations recently ended with a hung jury.

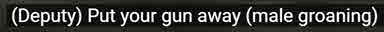

Back to Abelar. Deputy #3 seemingly got caught up in a complex, life-threatening situation not unlike what the Louisville cops faced. But there’s a hitch. Check out the voice-over caption that accompanies the 12:06 frame of the sheriff’s video (its accompanying background image was purposely blurred out):

“Put your gun away” was rapidly uttered by a male. It seems that seconds after Deputy #3 fired, one of her colleagues told her to holster her pistol. His comments carried a clear implication of disapproval.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

To be sure, another deputy might have handled things differently. From the beginning (see, for example, “When Cops Kill”) we’ve emphasized that differences in personality, experience and training greatly affect how officers react. What’s more, even “routine” policing is packed with chaos and citizen noncompliance. And while the post-Floyd era has led agencies to try to “fix” things by fashioning ever-more-complex rules to guide the police response, what the deputies faced on September 21, 2021 was decidedly extreme. We thus struggle to come up with a procedural “fix” that would have guaranteed a chronically misbehaving gunslinger came out unscathed.

Well, there is one approach. Set rule-making aside. Make in-depth, broadly-based, no-holds-barred discussions of the unforgiving circumstances that officers often encounter a major component of training and, as well, a routine part of every roll-call. Be sure to throw everything into the mix, including the foibles of citizens and cops. And by all means, don’t feel compelled to preordain (or even offer) “solutions.” You see, it’s precisely the “unsolvable” that we must squarely face.

UPDATES (scroll)

12/21/23 A Texas grand jury indicted suspended Austin police officer David

Sanchez with “felony deadly conduct” for killing Rajan Moonesinghe one year ago. Police responded to a

911 call about a man firing a rifle into their home. Officer Sanchez was first on scene. He saw Moonesinghe holding

a rifle, told him to drop it, and promptly opened fire, killing him. Security camera video depicts Moonesinghe

yelling into his home at an “intruder” (there was none), then firing two shots. D.A. Jose Garza, who is

at odds with the police, criticized the chief’s support of Officer Sanchez. Videos:

Bodycam Security camera

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Craft of Policing special topic

R.I.P. Proactive Policing? Routinely Chaotic Speed Kills When Cops Kill

Posted 9/5/23

WHEN (VERY) HARD HEADS COLLIDE (II)

What should cops do when miscreants refuse to comply?

Refuse to comply?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Other than depicting a police officer’s backside, what else is unusual about this picture? Look closely. That shiny Lexus two Ohio cops tangled with on August 24 lacks a rear license plate. According to Blendon Township police Chief John Belford, it lacked a front license plate as well (click here for his video statement and here for our transcript). Indeed, the vehicle was probably unregistered. According to police accounts and records we dug up in municipal court files – we’ll get into that below – its driver and sole occupant, twenty-one year old Ta’Kiya Young, was likely unlicensed.

But first, let’s examine the circumstances that led to the ultimately tragic encounter (click here for the police chief’s initial Facebook statement, posted one day after the event, and here for his follow-up account.) Blendon Township, a prosperous community of about 10,000 residents, lies about sixteen miles northeast of Columbus, the state capital. Blendon’s smallish, full-service police department employs seventeen sworn officers, including two detectives and eleven patrol officers. Chief Belford reported that immediately preceding their contact with Ms. Young, two patrol officers were in the Kroger parking lot, helping a locked-out citizen get back into their car. That’s when a Kroger employee ran up and informed them that Ms. Young, who was walking up to her nearby Lexus (it was parked in a handicapped slot) stole liquor from the store. She had supposedly been in the company of other shoplifters, but they already fled.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

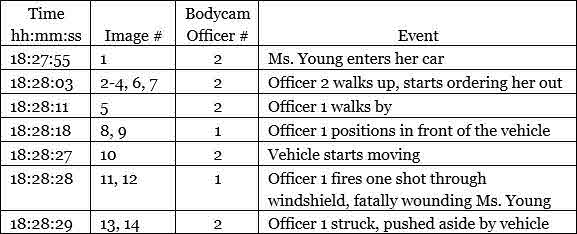

So the cops shifted their attention. Here’s a sequence of images from their bodycams:

Things happened very quickly. Eight seconds after Officer 2 began ordering Ms. Young to exit her vehicle, Officer 1 walked by and planted himself in front of the car (a clearly poor move that we’ll come to later). Only nine seconds after that, the car began to move. Veering sharply to the right, it knocked Officer 1 aside. Having already unholstered his gun, he instantly fired. His round penetrated the windshield (images 11 and 12) and fatally wounded Ms. Young. Even so, she managed to safely steer the car to the shopping center’s walkway and, as the officers ran alongside, bring it to a halt. Ms. Young was locked inside, so the cops broke in to render aid. Alas, it proved too late.

Police haven’t mentioned finding any ill-gotten merchandise in Ms. Young’s car. According to her lawyer, there was none, as she had been observed leaving the liquor in the store. Her decision to do so may have been spurred by employee reaction to the large-scale shoplift in which she allegedly participated. But the absence of loot certainly provides grist for the lawsuit being filed by her family.

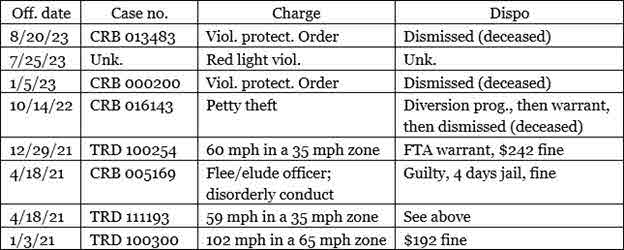

Ms. Young did refuse to cooperate with police. Her flight also placed Officer 1 at great risk. Had she decisively stepped on the gas or failed to swing the vehicle away, he might have been killed. Her reckless behavior reflects an unfortunate pattern of conduct that’s been documented in the municipal courts of Franklin and Sandusky counties:

We’ve often cautioned about the chaotic nature of police-citizen encounters (see, for example, “Routinely Chaotic”). Ditto, citizens’ frequent reluctance to peacefully comply (“Fair but Firm”). Ditto, the risk that rushed responses might cause needless harm. (“Speed Kills”). Here, all three concerns seem to apply. Still, the circumstances that Officers 1 and 2 faced were unforgiving from the start. An alleged participant in a major shoplift episode was about to drive away. Worse still, neither officer had apparently connected with Ms. Young in the past, and her vehicle’s lack of license plates deprived them of some potentially very useful information.

Even so, Officer 2 (their names have not as yet been released) didn't treat the situation as a dangerous felony stop. He hurried to the driver's door and, without drawing his gun, ordered Ms. Young from the vehicle. But she refused to exit. And kept refusing. Officer 2 apparently tried to open the car’s door (see images 7-9 above). But it was locked.

Officer 1 noticed. Perhaps to emphasize the seriousness of the situation, or simply as a bully tactic, he placed himself in front of the vehicle and drew his pistol. As one might expect, police trainers have condemned his approach. While drawing a gun might be justified, accepted practices clearly rule out standing in front of a suspect’s car. (Imagine what would have happened had Ms. Young really stepped on the gas.) Still, once the vehicle began to move and he got bumped, firing a shot could be justified as self-defense. Blendon PD’s relevant use of force rules are typical for the genre. Here’s an extract:

An officer should only discharge a firearm at a moving vehicle or its occupants when the officer reasonably believes there are no other reasonable means available to avert the imminent threat of the vehicle, or if deadly force other than the vehicle is directed at the officer or others.

A horrific outcome had been eminently avoidable. That it wasn’t can be attributed to the unholy combination of two very hard heads: one a citizen’s; the other a cop’s. We wrote about a like pair fourteen years ago (“When Very Hard Heads Collide”). But for a notorious recent example there’s the paradigm-shifting episode involving Minneapolis cops and George Floyd (“Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job”). It started out in a similar fashion, with officers responding to a call about a shoplifter who wouldn’t give things back. Rookie cop Thomas Lane, the first officer on scene (he’s now in Federal prison) managed to get Mr. Floyd out of his car and onto the sidewalk, no harm done. Unfortunately, Mr. Floyd (he had a substantial criminal record) soon stopped playing nice. That frustrated a senior cop (Derek Chauvin, now also imprisoned). So he came up with a “better idea.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

What’s the fix? Three years ago our Police Chief op-ed “Why do Officers Succeed?” pointed out that cops successfully handle fraught situations involving misbehaving citizens every minute of every day. While tactical blunders do happen (our Strategy & Tactics essays are riddled with examples) Officer 1’s purposeful, obviously dangerous positioning seemed clearly intended to convey a message. And to the cop’s likely dismay, his challenge was accepted. But there’s no need to craft yet another elaborate set of rules. The solution is really quite straightforward. Impress on our public servants that society can’t afford non-compliance with accepted procedures, and especially by its badge-wearers. In the fraught atmosphere that characterizes present-day America, their blunders truly are an invitation to disaster.

UPDATES (scroll)

8/14/24 In August 2023 two Blendon Township, Ohio police officers tried to detain Ta’Kiya Young, 21 as she set to drive off from a Kroger store with allegedly shoplifted liquor. As one officer ordered her out of the car, his partner, Connor Grub, positioned himself in front of the vehicle, blocking it with his body. Ms. Young then eased the car forward. Officer Grubb opened fire, killing the expectant mother and her unborn baby. He has just been indicted for murder, involuntary manslaughter and felony assault in connection with their deaths.

6/4/24 In January Minneapolis D.A Mary Moriarty charged State Trooper Ryan Londregan with murder for fatally shooting Ricky Cobb II as he tried to drive away from a July 2023 traffic stop. But “new evidence” just led her to drop all charges. Londregan, she said, would testify that he fired because Cobb reached for a handgun (Cobb’s criminal record prohibited him from having guns, and one was found). A trainer would also testify that Londregan was never instructed not to fire into a moving vehicle. Governor Tim Waltz, who had opposed charging the trooper, applauded the decision. But a lawyer for Cobb’s survivors (they have sued in Federal court) bitterly criticized the D.A.’s change of heart.

1/25/24 Elected in 2022 on a promise of “sweeping changes” after the George Floyd episode, Minneapolis D.A Mary Moriarty filed murder and other charges against State Trooper Ryan Londregan for the July 2023 shooting of Ricky Cobb II. Trooper Londregan fired when Mr. Cobb, a Black man, tried to drive away from a traffic stop after troopers discovered he had a warrant and ordered him to step out. A gun (which Mr. Cobb was prohibited to possess because of a prior conviction) was later found in his car.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED ARTICLES

Why do Officers Succeed?

RELATED POSTS

Craft of Policing special topic

Point of View Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job Fair but Firm Speed Kills Routinely Chaotic

When Very Hard Heads Collide

Posted 1/9/23

RACE AND ETHNICITY AREN’T PASS/FAIL

DOJ quashes an attempt to obstruct rentals to Blacks and Hispanics

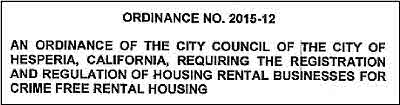

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. After a decade-and-a-half of trawling for juicy crime and justice developments on which to expound, it’s not often that we’re (totally) surprised. But that December 14 piece in the Los Angeles Times was definitely a head-snapper. It wasn’t just the headline: “Accused of illegally evicting Black and Latino renters, SoCal city, sheriff to pay $1 million.” After all, concerns about racial bias are part of everyday discourse. Instead, it was the reveal that a community of about 100,000 middle-and-upper working class residents got so upset about crime that its leadership enacted an ordinance, effective January 1, 2016, requiring that prospective occupants of rental property pass criminal background checks and thereafter stay out of trouble.

That’s right: obtaining and retaining permission to live in a rental was contingent on approval by the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, which runs Hesperia’s police. Cops notified landlords when tenants stepped out of line. And there were penalties for property owners who failed to heed official “requests” to evict.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Actually, running checks on would-be tenants isn’t anything new. Based on a concept developed by the International Crime-Free Association, “crime-free rental housing” programs are in force at scores of communities across the U.S., including “more than a quarter of all the local governments” in California. Their implementation varies. Kansas City landlords conduct criminal background checks on prospective tenants and must take the “frequency, recentness, and severity” of their criminal history into account when deciding whether to rent. Police promptly inform owners about tenants’ criminal activity, arrests and drug use, and may “actively push” for eviction. However, that decision is supposedly left for landlords to make. KCPD’s online guide describes the program as “designed to help keep illegal activity off rental property” and provides contact information for the officers who administer it at each patrol division.n of strategy and tactics essays

Problem is, some cities have apparently gone well beyond “pushing” for eviction. Hesperia’s law, for example, flat-out prohibited renting or leasing properties to persons with criminal records. What’s more, once individuals were housed, landlords were required to evict persons who cops said had misbehaved. These mandates, and many others, formed a comprehensive, twelve-page ordinance signed by Mayor Eric Schmidt in November 2015. Property owners had to register rental properties with the city, pay an annual fee, and comply with a host of to-do’s. Landlords were required to collect personal identifying information from every prospective adult occupant (not just the person signing a lease) and pay to have each one checked for arrests and such by a commercial service. Rental agreements had to include warnings that entire households would be evicted should any member commit a crime in or near their abode. And the threat had to be carried through. Problem is, some cities have apparently gone well beyond “pushing” for eviction. Hesperia’s law, for example, flat-out prohibited renting or leasing properties to persons with criminal records. What’s more, once individuals were housed, landlords were required to evict persons who cops said had misbehaved. These mandates, and many others, formed a comprehensive, twelve-page ordinance signed by Mayor Eric Schmidt in November 2015. Property owners had to register rental properties with the city, pay an annual fee, and comply with a host of to-do’s. Landlords were required to collect personal identifying information from every prospective adult occupant (not just the person signing a lease) and pay to have each one checked for arrests and such by a commercial service. Rental agreements had to include warnings that entire households would be evicted should any member commit a crime in or near their abode. And the threat had to be carried through.

Hesperia jusified the move by claiming that there was a “connection between rental properties and increased illegal activity and law enforcement calls for service.” But the Feds insist that was merely a smokescreen. What did they think was the real motive? According to DOJ’s lawsuit, “statements by City and Sheriff’s Department officials indicate that the ordinance was enacted with discriminatory intent and with the purpose of evicting and deterring African American and Latino renters from living in Hesperia.” Their data indicated that Black and Hispanic persons were far more likely than Whites to be denied housing, and once housed to be kicked out. HUD reported that “African American renters were almost four times as likely as non-Hispanic white renters to be evicted because of the ordinance, and Latino renters were 29% more likely than non-Hispanic white renters to be evicted.” Nearly everyone that got booted – 96.3% of individuals and 96.9% of households – lived in a Census block whose majority population was non-White. Yet “only 79% of rental households in Hesperia are located in majority-minority Census blocks.”

DOJ backed its claims of discriminatory intent with extracts from comments voiced by city council members and police managers during the hearings that preceded the law’s enactment (see link, pages 6-10). For example:

City Councilmember Russ Blewett: “the purpose of the ordinance was “to correct a demographical problem.” City Councilmember Russ Blewett: “the purpose of the ordinance was “to correct a demographical problem.”

- Mayor Eric Schmidt: “I can’t get over the fact that we’re allowing . . . people from LA County to ‘mov[e] into our neighborhoods because it’s a cheap place to live and it’s a place to hide’ and ‘the people that aggravate us aren’t from here,’ and that they ‘come from somewhere else with their tainted history’.”

- Sheriff’s Captain (and future City Manager) Nils Bentsen: “[Bentsen] compared the ordinance to his previous efforts evicting people in ‘a Section 8 house’ where ‘it took us years to ... find some criminal charges [and] arrest the people’.”

DOJ also heavily criticized the law’s alleged impact on innocents:

- A Black female householder’s repeated calls about an abusive boyfriend got her and her three children kicked out. Unable to afford other housing, they were forced to move “across the country.”

- A man’s “mental health crisis” led the expulsion of the householder, a Hispanic female, and forced her to relocate to a motel.

- A Black mother’s call for help led to the eviction of the whole family. Unable to secure a replacement rental, they moved away, leaving a teen daughter behind so she could complete high school.

Bottom line: Hesperia recently settled. While it will continue to regulate rentals, the Sheriff’s Department is out of the picture and the “crime-free” ordinance is no more. Hesperia has agreed to pay a $100,000 fine and is allocating nearly a million bucks to compensate the afflicted and fund projects intended to eliminate housing discrimination. “Civil rights coordinators” will be trained to assess progress during the five-year period that the consent decree is scheduled to run. Bottom line: Hesperia recently settled. While it will continue to regulate rentals, the Sheriff’s Department is out of the picture and the “crime-free” ordinance is no more. Hesperia has agreed to pay a $100,000 fine and is allocating nearly a million bucks to compensate the afflicted and fund projects intended to eliminate housing discrimination. “Civil rights coordinators” will be trained to assess progress during the five-year period that the consent decree is scheduled to run.

According to the Feds, the disparate outcomes and instances of individual harm weren’t by accident but stemmed from animosity towards Blacks and Hispanics. Bigotry, plain and simple. Neither the Complaint nor DOJ’s weighty, self-congratulatory press release indicated that the city might have had any legitimate reason whatsoever for making decisions that wound up falling hardest on Blacks and Hispanics. Consequently there was no need to address the factors that our Neighborhoods essays point out are associated with crime. Nor any need to mention the well-known path to a solution. For the record, let’s self-plagiarize:

…no matter how well it’s done, policing is clearly not the ultimate solution. Preventing violence is a task for society. As we’ve repeatedly pitched, a concerted effort to provide poverty-stricken individuals and families with child care, tutoring, educational opportunities, language skills, job training, summer jobs, apprenticeships, health services and – yes – adequate housing could yield vast benefits.

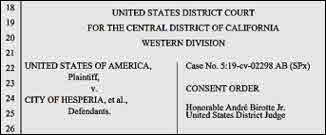

So was anything beyond racial animus at work? There was one intriguing hint. During hearings for the proposed ordinance, witnesses repeatedly blamed Hesperia’s crime on persons who relocated from Los Angeles. Mayor Eric Schmidt complained that “I can’t get over the fact that we’re allowing…people from LA County” to “mov[e] into our neighborhoods because it’s a cheap place to live and it’s a place to hide…[they] come from somewhere else with their tainted history.” And while DOJ’s Complaint didn’t get into causes beyond bias, it pointed out (by way of disagreeing with that shot at L.A.) that “approximately three-quarters of new Hesperia residents between 2012 and 2016 moved there from other parts of San Bernardino County.” Well, here’s a map:

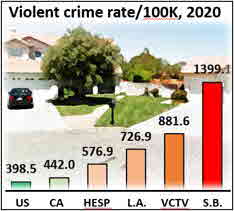

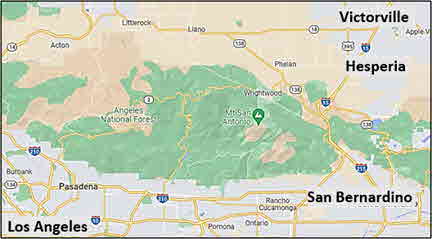

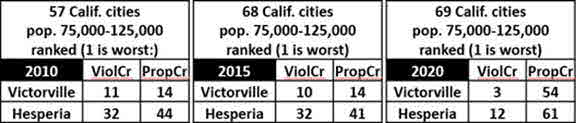

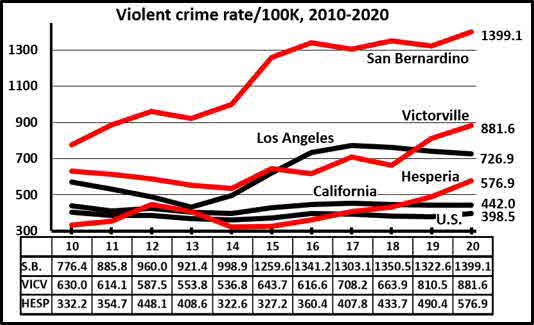

Hesperia (2020 pop. 95,163) has two sister cities, San Bernardino (pop. 216,784) and Victorville (pop. 122,958). Rating sites are lukewarm about each community. Niche awards Hesperia a “C” overall and a “C” for crime. Victorville and San Bernardino earn C-minuses for both. As usual, we turned to the FBI. Our top graph indicates that Hesperia’s 2020 violent crime rate fell between California’s overall and L.A.’s. Victorville’s rate came in considerably higher, and San Bernardino’s was simply appalling. These tables depict the outcome of rank-ordering the violent and property crime rates of all California cities. Remember, these are ranks, so #1 is worst:

Here’s how Hesperia and Victorville compared with other California cities of similar population size:

Both sets of tables suggest that San Bernardino and Victorville have developed a serious violent crime problem, and that Hesperia seems to be trying to catch up. Their deteriorating positions are evident in this graph, which depicts violent crime trends for the U.S., California, Hesperia, Victorville and San Bernardino over the full decade:

Check out those red trend lines. From about 2015 on, Hesperia, Victorville and San Bernardino seemed essentially on the same track. We computed r (correlation) scores. These can range from zero, meaning no relationship, to one, denoting a perfect relationship. Between 2015-2020 the correlation between Hesperia’s rates and Victorville’s was a sky-high .94, and between Hesperia’s and San Bernardino’s a slightly lower but still robust .79.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

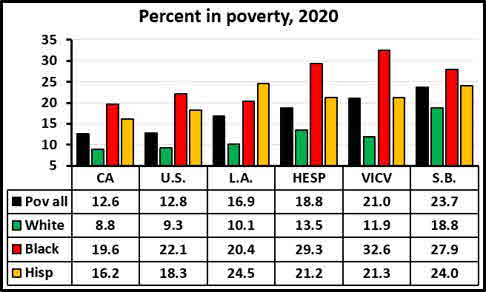

Crime aside, what about economic conditions? Hesperia was never an affluent place. Still, 2020 Census data reveals that its economy is in considerably better shape than Victorville’s or San Bernardino’s:

Yet in Hesperia as elsewhere, the burden of poverty falls far most heavily on Blacks and Hispanics. But there’s not a hint that economic inequality came up during debate. Instead, Hesperia’s officials took a conceptual shortcut. Equating crime with race and ethnicity, they sought to prevent the former by reapportioning the latter. Consider, for example, councilmember Russ Blewett’s shameful comments:

…Russ Blewett stated the purpose of the ordinance was “to correct a demographical problem.” He stated he “could care less” that landlords and organizations…disagreed with him about the ordinance, and stated that the City needed to “improve our demographic.” Blewett also stated that “those kind of people” the ordinance would target were “no addition and of no value to this community, period,” and that he wanted to “get them the hell out of our town.”

In the end, it wasn’t criminal record checks that brought DOJ’s reproach. Whether or not everyone who voted for the ordinance suffered from racial animus, its odor suffused the proceedings. And the consequences could make it even tougher for well-intentioned efforts to improve economically-challenged, violence-stressed neighborhoods to take hold.

UPDATES (scroll)

10/15/24 A Missouri apartment management firm has been sued by DOJ for violating the Fair Housing Act by categorically banning prospective tenants “with any past felony conviction and certain other criminal histories,” no matter the nature of the crime nor when it occurred. Doing so, according to DOJ, unlawfully discriminates against persons of color. Although criminal histories “are known to have significant racial disparities”, they’re not considered to accurately depict current conduct or predict future behavior.

8/16/24 “Crime-free” housing programs which deny rentals to persons with criminal arrests or convictions supposedly enhance community safety. But the U.S. Justice Dept. just placed local governments on notice that there is “no evidence” that these programs have a beneficial effect. Instead, they “disrupt lives, force families into homelessness and result in loss of jobs, schooling and opportunities for people who are disproportionately low-income people of color – all in violation of federal law.”

12/28/23 California Assembly Bill 1418 bars localities from enacting “crime-free policies” that forbid rentals to persons with prior criminal convictions. It will take effect on January 1st. Opponents of these laws point to research by RAND Corp. that found “no statistically meaningful relationship” between such laws and local crime rates. However, landlords will be allowed, should they wish, to check the records of prospective tenants and act on what they find (see 2/28/23 update). AB 1418 RAND study

11/27/23 Passed in 2018, California’s “Fair Chance” Act prohibits firms with five or more employees from asking about applicant criminal histories before they extend a “conditional” job offer. They can then inquire, but the circumstances that allow them to deny jobs are limited. Even so, a review of the Act’s efficacy reveals that it’s mostly benefited persons who perform unskilled labor and don’t directly interact with customers. Most employers otherwise continue looking into criminal histories in advance, and persons with convictions are unlikely to prevail even if they appeal.

7/21/23 Does having a criminal record make it much more likely that a prospective landlord will turn you down? Is that problem even worse for Blacks and Hispanics? A study of responses by Ohio landlords to applications submitted by experimenters through an online rental website says absolutely, yes. And the problem was worse for gentrifying neighborhoods. Half the inquiries indicated that applicants had a criminal record, and race and gender were conveyed through the applicants’ (fictitious) names.

5/10/23 An academic study based on 2016-2018 data that focused on Milwaukee’s assault “hot spots” concludes that landlords contribute to the persistence of crime in poor neighborhoods by neglecting their properties, failing to properly screen tenants, and relying on evictions, thus creating a cycle that leads to more crime.

2/28/23 A bill introduced in the California State Assembly would bar localities from enacting “crime-free policies” that require landlords to conduct criminal background checks on prospective tenants and prohibit rentals should a would-be tenant or occupant have a prior criminal conviction. Evictions of current renters or household members would also be barred unless they are convicted of a felony. But landlords continue to be free to devise and enforce background check and eviction policies on their own (see 12/28/23 update).

1/10/23 DOJ has filed a motion in support of a lawsuit against a Massachusetts rental housing firm that uses SafeRent, a commercial algorithm which evaluates the likelihood that prospective tenants might default. According to the suit, which alleges Federal civil rights violations, SafeRent discriminates against Blacks and Hispanics. Although they often do have lower credit scores, DOJ argues that they’re also more likely to use housing vouchers, which affords the means to pay rent. DOJ Motion

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Neighborhoods essays

What’s Up? Violence. Where? Where Else? Fix Those Neighborhoods!

|