|

Posted 3/19/22

A SHOW-STOPPER FOR SHOT-SPOTTER?

Gunshot detection technology leads progressives to cry foul

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Nowadays accusations of racially-biased policing seem commonplace. Problem is, law enforcement has always been an incubator of conflict. Given the complexities of policing, why officers sometimes act imprudently can be difficult to pin down. So when a respected organization such as the ACLU claims that a popular and supposedly objective law enforcement tool can make things worse one must simply have a look.

We’re talking gunshot detection. A comprehensive report by Chicago’s Inspector General focuses on ShotSpotter, whose sensors are at work in over one-hundred American cities. In Chicago they cover about half of the city’s police districts. Alerts don’t go directly to CPD. Instead, they’re electronically transmitted to ShotSpotter, where analysts work around the clock to filter out fireworks and non-firearm noises “and publish confirmed gunshots to police.”

According to the MacArthur Center, though, Chicago’s deployment of ShotSpotter – it’s at work in twelve of twenty-two districts – does no good. Instead, it “tracks and exacerbates Chicago’s racial divide”:

The Chicago Police Department has a long history of excessive force, illegal and discriminatory stop-and-frisk, and other abusive policies and practices. ShotSpotter is a tool and tactic that contributes to these problems. It exacerbates police bias towards marginalized communities and foments distrust and fear among residents.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

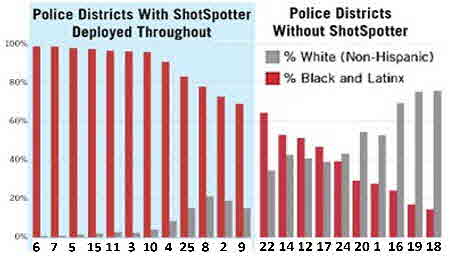

In a recent court filing the Center submitted the above graphic (we slightly tweaked it to fit). As they point out, it illustrates that sensors are only located in police districts that are predominantly populated by persons of color.

Of course, if ShotSpotter worked as advertised, its deployment would be welcomed by everyone but criminals. MacArthur, though, insists that the technology is fundamentally defective. Chicago P.D. officers reportedly answered 46,743 ShotSpotter alerts between July 1, 2019 and April 14, 2021. But in only 5,114 instances – 10.9% – did cops confirm that a gun-related event actually took place. (And in only 14 percent that a crime even occurred.) Bottom line: “There is no good evidence that ShotSpotter can reliably distinguish the sound of gunfire from other loud, impulsive noises.”

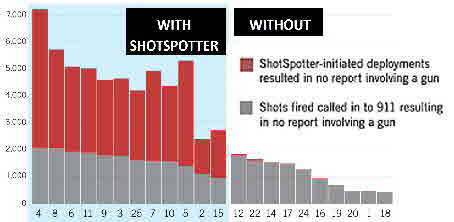

MacArthur’s filing includes a second image (see below) that depicts unverified gunfire alerts from both ShotSpotter and citizen 911 calls. It supposedly illustrates how Chicago uses exaggerated accounts of gunplay in areas predominantly populated by persons of color to justify “racialized and oppressive patters of policing” (i.e., intensive enforcement, stop-and-frisk, etc.)

MacArthur’s analysis was triggered by an actual killing, which is discussed below. But first, what should count? Considering the realities of the urban environment, the Center’s insistence that reports of gunfire are meaningless unless they’re confirmed seems unrealistic. If there are no suspects at hand and no one got hurt, expecting busy cops to, say, scour sidewalks and streets for bullet casings seems a stretch.

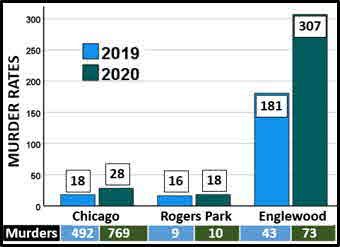

That Chicago singled out twelve districts is not in doubt. What is in question is why. And we have a pretty good idea. Our “Neighborhoods” essays have consistently demonstrated that poverty, which disproportionately burdens persons of color, is strongly associated with violence. This image from “The Usual Victims” contrasts murders and murder rates for two Chicago neighborhoods, Rogers Park (24th. police district, no ShotSpotter) and Englewood (7th. police district, with ShotSpotter). Rogers Park, pop. 51,270, is 41.9% White and its poverty level is 26.3%. Englewood, pop. 26,025, is 95% Black and its poverty level is 46.3%. That Chicago singled out twelve districts is not in doubt. What is in question is why. And we have a pretty good idea. Our “Neighborhoods” essays have consistently demonstrated that poverty, which disproportionately burdens persons of color, is strongly associated with violence. This image from “The Usual Victims” contrasts murders and murder rates for two Chicago neighborhoods, Rogers Park (24th. police district, no ShotSpotter) and Englewood (7th. police district, with ShotSpotter). Rogers Park, pop. 51,270, is 41.9% White and its poverty level is 26.3%. Englewood, pop. 26,025, is 95% Black and its poverty level is 46.3%.

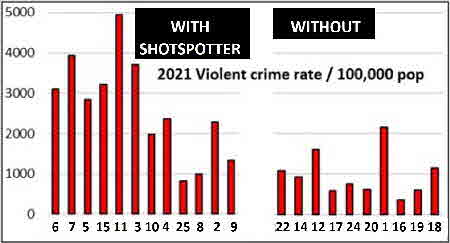

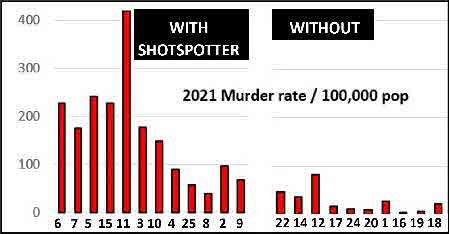

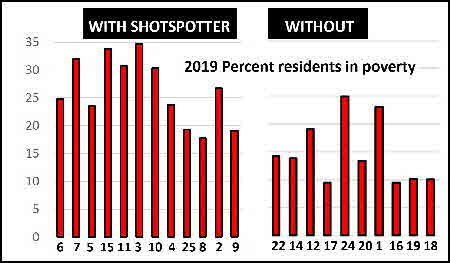

Our present inquiry uses Chicago PD crime data to probe poverty and violence in the precincts identified by MacArthur. Since police district and neighborhood boundaries differ, police district populations are from johnkeefe.net. His tallies reflect the 2010 census but remain useful for comparison. Our graphs follow MacArthur’s format, with the twelve police districts that deploy ShotSpotter on the left, and the ten that don’t on the right.

It takes only a glance to confirm that ShotSpotter deployment is biased towards the high-violence precincts. As for the link with economic conditions, the below graph reports percentage of residents in poverty at each precinct’s ZIP from the 2019 ACS.

As one would expect, higher-violence precincts tend to be substantially poorer. Such as the 10th., where nearly one in three live in poverty. That’s where a ShotSpotter device reported gunfire during the early morning hours of March 29, 2021. As police arrived an adult male and his 13-year old companion, Adam Toledo, ran off. Toledo had a gun, and within moments an officer reportedly mistook a gesture as a lethal threat and shot the teen dead. (For more about the encounter see “Regulate. Don’t Obfuscate.” For a recent news article about the episode click here.)

Responses to reports of gunfire can place cops and citizens – both innocent and not-so-innocent – at considerable risk. But until recently we didn’t know that a ShotSpotter alert – again, in Chicago – supposedly led to a wrongful arrest for murder. On May 31, 2020, Chicago resident Michael Williams, 64 brought Safarain Herring, 25 to an emergency room. Herring had been shot dead. Williams told police he was giving Herring a ride when gunfire rang out from a passing vehicle. But video from the gunshot location identified by ShotSpotter showed Williams’ car. And it was parked.

There was apparently little other evidence. Williams’s criminal history – he had served prison terms for attempted murder, robbery and a gun crime – may have sealed his fate. He was arrested and jailed pending trial. Months later public defenders submitted an elaborate Frye motion that criticized ShotSpotter’s technical claims as “unscientific and reckless.” What’s more, ShotSpotter employees were accused of purposely changing the location of the gunfire to where the video depicted Williams’ vehicle had parked. MacArthur lawyers joined in with a motion contending that ShotSpotter grossly exaggerates how much gunfire actually takes place.

Vice Media quickly posted the juiciest parts of the damning assessments online. The Associated Press followed up with a major investigative piece that blasted ShotSpotter. Its work was picked up by news outlets throughout the U.S.

Alas, the Frye motions on which the newsies relied weren’t totally accurate. Among other things, ShotSpotter employees didn’t change the location of the gunfire: they had always mapped it at the same intersection. The original street address was incorrect, though, so that was (innocently) changed. ShotSpotter demanded retractions; ultimately, every outlet but Vice apparently complied. (Scroll to the end of AP’s news piece to read its correction.) As for Vice, ShotSpotter’s suing. Still, the ruckus didn’t help the criminal case. In February 2022, after Williams had spent nearly one year locked up, prosecutors dismissed the case for lack of evidence.

Chicago’s contract with ShotSpotter runs through August 2023. Two years earlier, only five days after AP’s original blast, the city’s Inspector General issued a report report disparaging the technology’s usefulness. In line with MacArthur’s findings, the IG suggested that ShotSpotter was actually making things worse:

CPD responses to ShotSpotter alerts rarely produce evidence of a gun-related crime, rarely give rise to investigatory stops, and even less frequently lead to the recovery of gun crime-related evidence during an investigatory stop...Additionally, from qualitative review of ISR narratives, OIG found evidence that CPD members’ generalized perceptions of the frequency of ShotSpotter alerts in a given area may be substantively changing policing behavior.

However, the door was left somewhat open. After all, poor police recordkeeping (meaning, about the circumstances of ShotSpotter calls) could be “obstructing a meaningful analysis of the effectiveness of the technology.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Academic reviews of ShotSpotter’s usefulness are decidedly mixed. An early (1998) study of gunshot detection technology (GDT) reported that it “accurately detected” 80 percent of test shots and accurately placed 72 percent. While GDT seemed to work well for pistols and shotguns, though, it was stumped by an MP-5 assault rifle. A study of a selected neighborhood also revealed that police were responding somewhat less quickly to GDT alerts than to citizen calls. Most importantly, there were nearly three times as many of the former. Whether that reflected GDT’s technical failings or citizen underreporting of gunfire couldn’t be determined. But GDT caused officer workloads to skyrocket. Two decades later, though, a DOJ-funded evaluation of ShotSpotter in Denver, Milwaukee and Richmond (Calif.) concluded that GDT actually reduced response times:

Evaluation findings suggest that GDT [gunshot detection technology] is generally but not consistently associated with faster response times and more evidence collection, with impact on crime more uneven but generally cost-beneficial. We also conclude that agencies should implement GDT sensors strategically, train officers thoroughly, ensure that GDT data are used and integrated with other systems, and engage with community members early and often.

In the end, there is little to suggest that gunshot detection technology can lessen firearms violence. A study of gun homicides in 68 “large metropolitan counties” between 1999-2016 reported that ShotSpotter “has no significant impact on firearm-related homicides or arrest outcomes.” Really, expecting a narrow technical approach to ameliorate the consequences of America’s murderous affair with the gun seems a stretch. Being promptly alerted to gunfire seems like a good idea. But doing it right can require a large police force and prove very expensive, to say nothing of intrusive. In this highly fraught, post-George Floyd era, we might do better by keeping things at a lower key and investing in human capital.

You know, our neighborhoods. And their cops.

UPDATES (scroll)

6/24/25 Just passed by the House, H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act would (among many other things) Federally deregulate silencers. At present, they require special vetting and the payment of a $200 fee. Senate bill 1162, the SHORT Act would remove similar requirements (pre-approval and a

fee) that apply to “short-barreled firearms” (rifles with barrels under 16” and shotguns with barrels under 18”.) Instead, they would be

considered ordinary firearms. Gun enthusiasts say they favor silencers because they protect hearing; skeptics fear they would make it harder for police and citizens to react to shootings.

12/12/24 Phillipsburg, New Jersey (pop. 15,000) reportedly suffered five shootings in the last decade where someone was wounded or killed. But last year it used $297,000 in COVID-19 funds to install ShotSpotter. Many other small cities with few shootings have done likewise. As criticisms of ShotSpotter’s effectiveness has moved large cities to question its use, ShotSpotter has been aggressively marketed to small places. And their assessment of its usefulness has been largely positive.

11/13/24 A newly-published study evaluates the effects of gunshot detection technology (ShotSpotter) in Kansas City between its implementation in 2012 and September 2019. Comparing ShotSpotter and non-ShotSpotter areas, it concludes that ShotSpotter significantly increased the number of gun recoveries and decreased “shots fired calls for service.” However, ShotSpotter had no observable effects on the frequency of fatal and non-fatal shootings, or on the number of assaults or robberies committed with a firearm. It concludes that given its considerable costs, ShotSpotter’s benefits were questionable.

11/11/24 Shot-spotter and license plate readers helped lead Berkeley, Calif. police to San Francisco resident Jeffrey Darren Hue. According to police, Hue staged a series of shootings near the UC Berkeley campus during the late evening hours of October 26. A search warrant at his residence uncovered a veritable arsenal of assault weapons, handguns, magazines and ammunition. Arrested for a string of felonies, Hue is being held on $80,000 bond. BPD news release

10/7/24 In an editorial entitled “Two weeks and too many bodies on the streets,” the editors of the Chicago Tribune implore Mayor Brandon Johnson to reinstate ShotSpotter. Its absence, they write, has already led to six instances of bodies lying on the streets for extended periods after shots are fired and no one calls 9-1-1. An alderman complained that a 14-year old’s body wasn’t found for an hour. “An ambulance could have been dispatched within minutes, but instead a young man bled out on the street.”

9/25/24 Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson followed through on his pledge to let the contract expire. And forty minutes after ShotSpotter ceased operating, the city suffered its first shooting not picked up by the device. Although aldermen “overwhelmingly” voted to keep ShotSpotter, and many community members agreed the technology made them feet safer, the mayor opted to seek out supposedly better and less costly means to promptly alert authorities to gunfire. ShotSpotter indicated it will re-apply.

9/13/24 ShotSpotter has drawn negative reviews for false alarms. And for “over-aggressive” police responses. But the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab points to a potentially major benefit: quicker, possibly life-saving aid to gunfire victims. Its study reveals that when ShotSpotter goes “live,” fatality rates drop by four percentage points. Chicago’s overall gunshot fatality rate is 17 percent, so ShotSpotter can reduce the odds of death by one-quarter. There’s “a 3-in-4 chance that the technology saves about 85 lives per year.” If true, that seems very significant.

7/24/24 Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s promise to end the contract with ShotSpotter is applauded by progressives, who blame the technology for false alerts that lead to over-policing minority areas. But the aldermen who represent those Districts largely favor the technology. So they voted to empower the City Council to decide whether the contract will be renewed. That sets up a clash whose resolution is uncertain. Meanwhile a ShotSpotter alert on July 10 summoned officers to the crime-impacted Grand Crossing neighborhood, where they found a 15-year with a gunshot wound to the head. He later died.

6/21/24 Since 2015 New York City has spent “more than $45 million” on ShotSpotter. But the City Controller calls it a waste of money. According to an audit, even when Shot Spotter is supposedly working well, only twenty percent of its alerts correctly identify shootings. Meanwhile numerous real shootings go undetected. So the Controller wants to terminate its contract with the operator, SoundThinking, when it comes up for renewal in December. But NYPD insists that a shutdown would create a “less safe working environment for officers and an increased chance of violent encounters for all New Yorkers.”

2/14/24 Chicago’s progressives are applauding Mayor Brandon Johnson’s decision to carry through on his promise to cancel the contract with ShotSpotter, whose gunshot detection sensors are deployed in some of the city’s most violent sectors. But with nearly 3,000 shootings in Chicago last year, his move, which will take effect in October, is opposed by law enforcement, which values the instant notifications that the sensors can bring, independently of 9-1-1. (See 4/5/23 update)

11/16/23 Does implementing gunshot detection technology (GDT) reduce shootings? An academic study of its effects in Kansas City revealed that its presence led to the recovery of more guns and ballistic evidence and fewer shots fired calls for service. But the actual number of gun-involved criminal incidents (aggravated assaults, robberies, etc.) with actual or intended human victims remained unaffected. Researchers suggest that reducing these might best be accomplished though other approaches.

4/5/23 Elected by a slim margin, Brandon Johnson, Chicago’s progressive new Mayor, faces the city’s seemingly intractable problem of gun violence, with murder counts exceeding more populous Los Angeles and New York City. Johnson has “walked back” promises to cut police. But his plans to replace vacant officer slots with community workers, to increase detectives by cutting patrol, and to remove Shot Spotter gunfire detectors because they can cause dangerous encounters remain on the table. (See 2/14/24 update)

8/8/22 A mid-afternoon Shot-Spotter alert led officers in Chicago’s poor, violence-wracked Englewood area to a parked minivan. Nearby stood Alexander Podgorny, 29. He had a loaded handgun in his pockets. A loaded shotgun, a loaded AR-15 rifle, two handguns and writings containing “incoherent rants and references to mass shooting events” were in the front seat. A video from a nearby camera depicted a shotgun being fired into a park. Podgorny was arrested on weapons charges and a high bail was set.

7/19/22 An official Portland group formally recommended the adoption of ShotSpotter. It’s estimated that 84 percent of gunfire in the city goes unreported, and advocates feel that prompt notifications could help reduce violence. Opponents worry that the technology “will lead to over-policing in low-income and marginalized neighborhoods” and distract an understaffed police force. In response, boosters say that ShotSpotter would especially benefit low-income neighborhoods as they are the most impacted by crime.

4/15/22 Screening towers manufactured by Evolv that use sensors and AI to detect guns, knives and other weapons on pedestrians who pass through the devices are in use at many venues, including New York City’s Lincoln Center. They’re now being considered for the subways. But cost is a factor.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Neighborhoods special topic

The Usual Victims Regulate. Don’t “Obfuscate.” Mission Impossible? Location, Location, Location

Role Reversal

|