|

Posted 9/5/10

PREDICTIVE POLICING: RHETORIC OR REALITY?

New data-mining techniques promise to reinvent policing. Again.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Are we doing anything new or innovative with this data or are we just doing it better and quicker?” Lincoln police chief Tom Casady’s remarks probably led to a few gasps. Still, as the plain-spoken Nebraska native pointed out at a National Institute of Justice symposium last November, its focal topic was nothing new: “It is a coalescing of interrelated police strategies and tactics that were already around, like intelligence-led policing and problem solving. This just brings them all under the umbrella of predictive policing.”

Indeed, the strategy’s core concern – officer deployment – has its roots in the lowly pin map, a low-tech but remarkably versatile technique that was used to distribute officers and create beats well into the 1960’s. To be sure, pin maps had their limitations. Some variables weren’t easy to depict, and the process was clumsy, requiring constant attention and presenting the ever-present risk of getting poked. Computers soon stepped in, allowing managers to print detailed reports denoting the nature, incidence and distribution of crime for any area or time period that they wished.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

In the 1990’s police departments and academics formed alliances to solicit Federal funding for innovative crime-fighting programs. Notable initiatives of the era include Boston’s Operation Ceasefire, a juvenile violence reduction program, Richmond’s Project Exile, a hard-edged effort to incarcerate armed felons, and directed-patrol experiments targeting illegal gun possession in Kansas City and Indianapolis. Evaluations revealed that just like cops had always insisted, focused enforcement can have a measurable effect on crime and violence.

Academics also came to another conclusion long accepted by police, that crime and place were interconnected. “Hot spot” theory became the rage. Using probability statistics to distinguish hot spots from background noise, sophisticated software such as CrimeStat promised more efficient and effective officer deployment. It’s an approach that fit in well with Compstat, an NYPD innovation that uses crime data to hold precinct commanders accountable for identifying and responding to localized crime problems.

In 2009 NIJ jumped in, awarding predictive policing grants to Boston, Chicago, Shreveport, District of Columbia, the Maryland State Police, New York City and Los Angeles. Los Angeles, Bratton’s most recent fiefdom (he left earlier this year after completing his second and, by law, final five-year term) intends to go beyond crime data, gathering non-crime information from a variety of sources; for example, by extensively debriefing arrestees about their friends and associates. It’s not unlike the approach that fell flat in New York City, where police were until recently entering all sorts of information from stop and frisks into the department’s forbiddingly entitled “data warehouse.” (Complaints from civil-rights groups and privacy advocates recently led the governor to sign a state law that prohibits computerizing information about persons who aren’t arrested. Keeping paper records is still OK, though.)

And that’s not all. In an application for a second predictive policing grant LAPD proposes to generate daily crime forecasts using probability statistics. Police managers would apply the information to make deployment decisions, with predictions streamed to patrol cars and displayed on computer screens. One can hear the conversations now: “Hey, partner, what do you say we hit sector eight? It’s forty-percent certain that they’ll have a burg in the next thirty days!”

Yet whether a Jetsons approach can distribute cops more efficiently is doubtful. Impossibly spread out and with only half the per capita staffing of New York City, L.A. ‘s patrol coverage is so thin that there may be precious little left to calibrate. One can’t deploy fractions of a squad car, while diverting officers because computer models predict that the chances of crime are higher in one place than another is asking for trouble. Such predictions are subject to considerable error, and should the unexpected happen unprotected victims may be left wondering why they’re paying taxes. As for roving task forces, they’ve long been placed where crime is rampant, so more number crunching is unlikely to yield substantial additional benefits. (To read more about LAPD staffing click here and here.)

Really, it’s not as though crime analysts have been sitting on their keyboards waiting for a new paradigm to come along. Police computers have been churning data for decades. A few years ago your blogger, working as a consultant, developed a computerized system for generating gun trafficking leads from ATF tracing data. While it seemed to work well enough, there are never enough variables in the mix, or in the right weights or order, to escape uncertainty. Printouts can’t arrest anyone, and it takes plenty of shoe leather to sort through even the most fine-grained information, select likely targets and build a criminal case. At least to this observer, hopes that automation will substitute for cops are a pipe dream.

There are other concerns. At a time when many police departments are so beset with conduct, use of force, corruption and personnel issues that they’re on the verge of nervous breakdowns (think, for example, Denver, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Tulsa and North Carolina), obsessing over data may be a needless distraction. Measures can easily displace goals. Just ask cops in New York City, where more than a few are complaining that pressures from Compstat force them to make needless stops and unworthy arrests. Two well known academics (one is a former NYPD crime analyst) agree.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Alas, no grants are in the offing for rediscovering the craft of policing. Meanwhile, Bill Bratton, Compstat’s indefatigable booster, has left government service. Now a top security executive, he continues peddling his theories, albeit under the more expansive label of “predictive policing”:

“I predict [that in] the next five to ten years that predictive policing, we’ll be in a position with the information that creates the intelligence that will be available to us that we will be like a doctor, we’ll be working increasingly with the diagnostic skills of the various machines they get to work with, the tests they get to do, that is the next era.”

UPDATES (scroll)

3/7/25 In Glendale, AZ, patrol officers need not wait for dispatch to send them on a call. New technology allows them to set their patrol car’s GPS so they can listen in, live, to all 911 calls that originate within one-half to three miles away. That enables catching evildoers literally “in the act.” In one example, a nearby cop’s near-instant response to a 911 call about a man trying to burglarize vehicles led to his arrest well before the officers actually dispatched on the call arrived.

4/1/22 The officers who searched Breonna Taylor’s apartment were members of a team that was pioneering Louisville PD’s application of the “place network investigations” approach to combating crime in chronically beset areas. That strategy, which grew from academic research, is in use at a handful of cities, including Las Vegas, Dallas, Philadelphia and Tucson. A “holistic” version of “hot spots,” it also derives from the “PIVOT” approach developed and used in Cincinnati. But Louisville has dropped it.

2/4/22 During 2015-2016 Philadelphia police conducted a Predictive Policing experiment that focused extra police resources, including marked and unmarked patrol, on data-identified crime “hot spots.” An academic study of its effects recently led OJP’s Crime Solutions to assign the practice a “No Effects” grade. While an increase in marked patrol was associated with a reduction in property crime, violent crime significantly increased. Unmarked patrol demonstrated no effect on either crime type.

6/26/20 Santa Cruz, Calif., an early adapter of Predictive Policing, has banned it because it biases police attention towards areas populated by persons of color. Its use was suspended by a new police chief in 2017 because doing “purely enforcement” caused inevitable problems with the community. Santa Cruz also banned facial recognition software because of its racially-biased inaccuracies.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Cops Aren’t Free Agents Role Reversal Liars Figure Thin Blue Line Cops Matter

A Larger Force

Posted 7/11/10

THE KILLERS OF L.A.

DNA nabs three serial killers in four years, most recently through a familial search

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. From all the hoopla surrounding the arrest of the “Grim Sleeper” (so dubbed because after an unexplained hiatus he supposedly rose to kill again) one would think it marks the end of a decades-long quest to capture the city’s most murderous evildoer. Well, think again. Thanks to DNA, LAPD detectives have arrested three – that’s right, three – serial killers in the last four years, and Lonnie Franklin isn’t necessarily the most prolific.

April 30, 2007 was the day that society finally washed its hands of Chester Turner. Convicted of raping and strangling ten women and causing the death of a viable fetus, the middle-aged crack dealer had passed the final two decades of the twentieth century preying on prostitutes in the poverty-stricken neighborhoods that image-conscious politicians recently christened South Los Angeles but locals still call south-central.

In 2002 Turner’s imprisonment on a rape conviction led authorities to place his DNA profile in the state databank. One year later an LAPD cold-case detective matched DNA from a 1998 south-central murder to Turner. Assembling profiles from dozens of similar killings, the detective matched Turner to nine more. But there was a glitch. You see, three had already been “solved” with the 1995 conviction of another Los Angeles man, David Allen Jones.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

A mentally retarded janitor in jail for raping a prostitute, Jones initially denied killing anyone. Detectives finally badgered him into making incriminating statements in three cases. Only problem was, as the D.A. later conceded, his blood type didn’t match biological evidence recovered from his alleged victims. But prostitutes have complicated sex lives, so prosecutors convinced the jury that this apparent inconsistency wasn’t definitive.

Jones was exonerated and freed in March 2004. He was compensated $800,000 for his eleven years in prison.

Well, Turner’s DNA was present. At trial his attorney argued that it only proved that his client had sex with the women, not that he killed them. Jurors were unswayed. Turner is presently on death row awaiting execution.

During the mid-1970’s someone was raping and killing elderly white women in southwest Los Angeles county. After subsiding for a few years the murders resumed nearly forty miles to the east, in the Claremont area. By 2009 there were two dozen, all unsolved.

Meanwhile, back in south-central, detectives were still on the trail of one or more killers, as many more prostitutes were slain than could be attributed to Turner. Finally in 2002 Chief Bratton ordered his troops to form a cold-case squad. Detectives began comparing biological evidence from unsolved cases in south-central to the DNA profiles of sex-crime registrants. One of these was John Thomas, 72, a parolee who had been imprisoned for rape in 1978. Although his DNA didn’t match any of the south-central killings, it matched at least two of the southwest homicides. His time in prison also coincided with the interval between the waves of murder, and he was paroled to Chino, not far from Claremont.

Thomas was arrested in April 2009. After more DNA testing he faces trial in seven killings. Detectives think that he is responsible for others as well.

By 2008 the south-central investigation was stalled. All remaining crime-scene DNA had been compared to the DNA profiles of convicted felons in state and federal DNA databanks, without further success. Then, only two weeks ago, detectives received startling news: California’s DNA database had a partial match.

DNA identification focuses on thirteen known locations, or “loci,” in the human genome. Each contains chemical sequences that are inherited from one’s parents. The FBI considers it a match if crime scene DNA and suspect DNA have identical sequences at no less than ten loci, and there are no dissimilarities. Some analysts and state labs accept fewer. Now, unrelated persons will frequently match at one, two or even three loci, but the odds that they will share chemical sequences at, say, five or more loci are very low. (For more about DNA identification click here.)

A year ago California DOJ launched a familial DNA program, the first in the U.S. California’s DNA repository has DNA profiles for most convicted felons. Until recently the practice has been to report no match with DNA profiles submitted for comparison unless a sufficient number of loci (say, ten) are identical, and there are no dissimilarities. Now, in serious cases, the state will provide the name of any felon in its databank whose DNA profile, although not identical to the submitted DNA(dissimilarities exist at one or more loci) is sufficiently similar to suggest a familial relation. (Pioneered in Great Britain, this procedure has also been adopted by Colorado. It’s under consideration in other states and by the FBI.)

Detectives finally had their break. State analysts reported that a DNA profile from the south-central killings likely belonged to a brother or the father of a felon in the state databank. And it got better: that profile wasn’t from just one killing: it was from ten, seven in the late 1980’s and three between 2002-2007.

Detectives took on the father, who had lived in south-central Los Angeles for decades, as the likely candidate. Learning that he would be attending a birthday party at a restaurant, an undercover officer bussed his plates, utensils and leftovers. One assumes that yielded a complete, thirteen-loci DNA profile. Analysts compared it to the DNA found on the ten murder victims. There was no question: it was a perfect match.

Four days ago LAPD detectives arrested Lonnie Franklin Jr., 57. Although he has an extensive criminal record, including theft, assault, weapons offenses and, as recently as 2003, for car theft, his DNA had never made it into the state database. Without familial DNA, Franklin would have probably never been caught.

Dozens of south-central killings lack DNA and remain uncleared. However, detectives found guns in Franklin’s home, and since some victims were shot they’re hoping that ballistics can help. In any event, police are confident that, like Thomas, Franklin committed many more murders than what they can presently prove.

At last report, they think as many as thirty more.

Not everyone thinks highly of familial DNA. While California Attorney General Jerry Brown and police officials enthusiastically call it a “breakthrough,” the ACLU’s Michael Richter thinks that it could lead innocent persons to be harassed. Winding one’s way through family trees, he worries, “has the potential to invade the privacy of a lot of people.”

Richter’s fears seem overblown. Policing is more likely to threaten privacy interests when physical evidence is lacking. Struggling with its own prostitute serial-killer situation, Daytona Beach recently asked gun stores to identify everyone who bought a certain model of weapon during a two-year period (natch, the NRA is crying foul.) That’s intrusive, perhaps unavoidably so. DNA, including familial DNA, can prevent years of fruitless interviews and unproductive searches, to say nothing of more killings and a wrongful conviction. When properly used it’s everyone’s best friend.

Of course, good detective work is crucial. Every time that a new maniac comes to light there’s a tendency to go “aha!” and attribute all unsolved homicides to them, risking that some culpable parties will go scot-free. Pressures to clear cases have led to wrongful convictions (remember David Allan Jones?) And as we’ve pointed out before, multiple DNA contributors and mixed DNA samples can yield ambiguous, even incorrect results. In the end, CSI can’t do it alone. Proving that Franklin did more than have sex with his victims will require corroboration, either through statements, other physical evidence (like ballistics) or circumstantially, say, through his whereabouts and activities. It will certainly make for a fascinating trial.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

We could also do with a bit of introspection. What in the end detectives skillfully resolved was, for victims and their loved ones, solved far too late. Why did it take until 2002 to mount a cold-case campaign? Would we have responded differently had the victims been different or had the killings occurred in a more affluent area?

And one must wonder. Three killers (one convicted, two alleged) are locked up. Is there a number four?

UPDATES (scroll)

3/30/20 “Grim Sleeper” Lonnie Franklin, one of the first serial killers identified through familial DNA, died of apparently natural causes while awaiting execution. He had been on death row since his 2016 conviction for committing ten murders in South Los Angeles between 1985 and 2007.

2/10/19 Newport Beach (CA) police arrested James Neal, 76, after a familial search of FamilyTreeDNA.com, a consumer DNA, linked him to DNA recovered from the scene of the July, 1973 murder of an 11-year old girl. A positive match was apparently made after Neal was placed under surveillance in Colorado.

1/31/17 And the answer is...yes! Thanks to familial DNA Kenneth Troyer, 29, was identified as the killer of Polly Klaas, a Los Angeles County woman murdered in January 1976. Troyer was shot dead by deputies six years later after escaping from a California prison where he was doing for burglary. Authorities recently matched partial DNA from the murder to two of Troyer’s relatives, then made a positive match to DNA from Troyer that had been kept by the morgue.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Is Your Uncle a Serial Killer? DNA: Proceed With Caution The Ten Deadly Sins

The Usual Suspects Miscarriages of Justice: a Roadmap For Change

Posted 5/2/10

MORE LABS UNDER THE GUN

Resource issues, poor oversight and pressures to produce keep plaguing crime labs

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Thank God it got dropped. Now I can get on with my life.” That’s what a relieved thirty-year old man said last month as he left the San Francisco courthouse, his drug charge dismissed, at least for the time being. He’s one of hundreds of beneficiaries of a scandal at the now-shuttered police drug lab, where a key employee stands accused of stealing cocaine to feed her habit.

Problems surfaced last September when veteran criminalist Deborah Madden’s supervisor and coworkers became concerned about her “erratic behavior.” Madden was frequently absent or tardy, and when present often stuck around after closing hours. She had recently broken into another analyst’s locker and when confronted offered a flimsy excuse. By November her performance had deteriorated to such an extent that prosecutors thought she was purposely sabotaging cases.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

Coincidentally, a team of external auditors was in town to review the SFPD laboratory in connection with its application for accreditation. They weren’t informed that Madden had taken leave to check into an alcohol rehab clinic, nor that her sister told a supervisor that she found cocaine at Madden’s residence, nor that a discreet audit of the drug lab’s books revealed cocaine was missing from at least nine cases. Indeed, a formal criminal investigation wasn’t launched until February, when officers searched Madden’s residence. That turned up a small amount of cocaine and a handgun, which she was barred from having under state law because of a 2008 misdemeanor conviction for domestic abuse.

When interviewed by detectives Madden conceded filching “spilled” cocaine from five evidence samples. But she had an excuse. “I thought that I could control my drinking by using some cocaine.... I don’t think (it) worked.” Madden otherwise held firm, claiming that sloppy handling by lab employees caused “huge” losses in drug weights. “You just have to check weights of a lot of stuff, because you will see discrepancies. That’s all I’m going to say. I mean, I think you want to put everything on me, and you can’t because that’s not right.”

The external reviewers were never told about Madden. Released in March, their report nonetheless chastised the drug lab for being understaffed and poorly managed, with three drug analysts expected to process five to seven times as much evidence as the statewide average, thus affecting the quality of their work. Evidence wasn’t being properly tracked or packaged, precautions weren’t being taken against tampering, and scales and other equipment weren’t being regularly calibrated, making measurements uncertain.

Chief Gasçon shuttered the drug lab March 9, throwing a huge monkey wrench into case processing. That, together with Madden’s alleged wrongdoing, led the D.A. to dismiss hundreds of charges. Dozens more convictions are at risk because Madden’s criminal record was never disclosed to defense lawyers, depriving them of the opportunity to impeach her testimony.

So far Madden hasn’t been charged with stealing drugs from the lab (she’s pled guilty to felony possession of the small amount of cocaine found in her home.) Really, given how poorly the lab was run, figuring out just how much is missing, let alone what’s attributable to theft and what to sloppiness, may be impossible.

In “Labs Under the Gun” we reported on misconduct and carelessness at police crime labs from Detroit to Los Angeles. Here are a few more examples:

- On March 12, 2010 Federal prosecutors revealed that six FBI lab employees may have performed shoddy work or given false or inaccurate testimony on more than 100 cases since the 1970’s. The disclosure was prompted by the exoneration of Donald Gates, who served nearly three decades for rape/murder thanks to testimony by FBI analyst Michael P. Malone that one of Gates’ hairs was found on the victim. Only thing is, the hair wasn’t his, as DNA proved twenty-eight years later.

As it turns out, prosecutors were first alerted to problems with Malone and his coworkers as early as 1997, when the DOJ Inspector General issued a stinging report discrediting analytical work in the Gates case and others. It then took seven years for DOJ to order prosecutors to contact defense lawyers. Even then, nothing happened. “The DOJ directed us to do something in 2004, and nothing was done,” a prosecutor conceded. “This is a tragic case. As a prosecutor it kills you to see this happen.”

Gates was released in December 2009.

- There was good news on February 17, 2010: an innocent person was exonerated. There was also bad news: Greg Taylor, the man being freed, had served 17 years for murder, mostly because of false testimony that blood was found on his truck.

At his trial, jurors weren’t told that the presence of blood was based on a fallible screening test whose results were quickly disproven by more sophisticated analysis. There was no blood – it was a false positive. Yet the examiner who ran the tests, Duane Deaver, never let on. This wasn’t the first time: he had also kept mum about contradictory findings in an earlier case that resulted in the imposition of the death penalty. (That sentence was eventually vacated by a judge who rebuked Deaver for his misleading testimony.) Thousands of cases involving the lab are now being reviewed for similar “mistakes.”

- In December 2009 the New York State Inspector General disclosed that State Crime Lab examiner Garry Veeder had been falsifying findings for a stunning fifteen years. Writing one year after the analyst’s suicide, the IG reported that Veeder made up data “to give the appearance of having conducted an analysis not actually performed.” Veeder, who had conceded being unqualified, said that he relied on “crib sheets,” that others knew it, and that taking shortcuts was commonplace.

- In January 2009 the Los Angeles Times reported that goofs by LAPD fingerprint examiners caused at least two mistaken arrests. Reviews were ordered in nearly 1,000 cases, including two dozen pending trial. Six examiners were taken off the job and one was fired. Blame for the mismatches was attributed to inadequate resources and to lapses in training and procedures.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

In 2009 the National Academy of Sciences issued a blistering report criticizing some forensic science practices as bogus and most others as being far less scientific than what we’ve been led to believe. Virtually every technique short of DNA was said to be infused with subjectivity, from friction ridge analysis (i.e., fingerprint comparison) to the examination of hairs and fibers, bloodstain patterns and questioned documents.

That’s a stunning indictment. If analysts’ conclusions have as much to do with judgment as with (supposedly) infallible science, it’s more critical than ever to give them the training, resources and time they need to do a good job. But if resource-deprived, loosey-goosey, production-oriented environments are what’s considered state of the art, forensic “science” in the U.S. still has a very long way to go.

UPDATES

5/27/22 NIJ just released a major report, “National Best Practices for Improving DNA Laboratory Process Efficiency.” Spanning ninety pages, it covers a gamut of concerns, from selecting good employees to applying the best technologies “to speed the review of allelic ladders, controls, and samples” and “ensure the successful and timely completion of all testing, protocol development, and summarization of the validation work.” Alas, what’s not addressed, at least at any detectable length, is preventing errors of analysis and interpretation that can lead to grave miscarriages of justice.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Damn the Evidence - Full Speed Ahead! People do Forensics Labs Under the Gun

Forensics Under the Gun NAS to CSI: Shape Up!

RELATED ARTICLES AND REPORTS

Washington Post series on problems with forensic analysis

Posted 4/16/10

DNA: PROCEED WITH CAUTION

Subjectivity can affect the interpretation of mixed samples

“It’s an irony that the technique that’s been so useful in convicting the guilty and freeing

the innocent may wind up leading to wrongful convictions in mixture cases, especially

those with very low amounts of starting DNA.”

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Some might consider these words unduly alarmist. After all, no less an authority than the National Academy of Sciences has declared DNA to be the gold standard: “With the exception of nuclear DNA analysis...no forensic method has been rigorously shown to have the capacity to consistently, and with a high degree of certainty, demonstrate a connection between evidence and a specific individual or source.”

Yet for years there have been troubling signs that interpreting mixed DNA – meaning DNA that’s a blend from different contributors – isn’t as straightforward as some forensic “experts” claim. Consider the case of John Puckett, who was mentioned in “Beat the Odds, Go to Jail,” a post about random match probability, the likelihood that a particular DNA match could have happened by chance alone.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

In 2003 a partial DNA profile from an unsolved, decades-old rape/murder was compared against the California DNA database. Although the biological specimen was badly degraded and had fewer than the minimum number of markers the state usually requires to call a “match,” what was there was consistent with the DNA profile of Puckett, a convicted sex offender. Although nothing else connected him to the victim or the crime scene, Puckett was tried and convicted. Jurors said they were swayed by a prosecution expert who testified that the probability that the evidence DNA wasn’t Puckett’s was one in a million. It’s since been suggested that the government’s logic was faulty and that the true chance of a mismatch was actually one in three.

Since then the trustworthiness of the DNA processing has also come under attack. After sitting on a shelf for twenty-one years the biological sample was badly degraded, leaving only a tiny bit of DNA, and that being a mixture from both the victim and perpetrator. A growing chorus of scientists (and even police labs) warn that such factors can introduce dangerous uncertainties into DNA typing, making matching far more subjective that what one would expect.

But let’s turn this over to a real expert. Greg Hampikian, Ph.D (the source of the introductory quote) is professor of biology at Boise State University and director of the Idaho Innocence Project. One of the nation’s foremost authorities on forensic DNA, Dr. Hampikian jets around the globe giving advice and testimony and helping set up innocence projects. He graciously took the time from his busy schedule to give us a primer on DNA and the issues that attend to mixed samples.

An interview with Greg Hampikian, Ph.D.

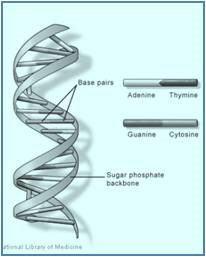

What is DNA?

DNA is the repository of all hereditary information. It provides the recipes for all the proteins that can be made by an organism. A stringy acid, it’s comprised of a chain of subunits or “bases,” the chemicals

Adenine, Guanine, Cytosine and Thymine. These are linked in pairs, with A only binding to T, and G to C.

Nuclear DNA, the kind most often used for identification, is found in twenty-three pairs of chromosomes – one inherited from each parent – that occupy the nucleus of every cell (except mature red blood cells). The complete set of nuclear chromosomes (all 23 pairs) is known as the “genome.” Sperm and egg cells contain only one of each of the 23 chromosomes, and thus have half the DNA of other body cells.

Is the full genome used for identification?

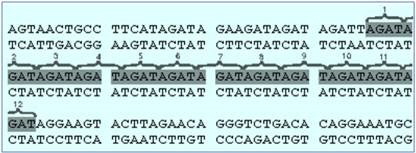

No. A genome is comprised of millions of linked pairs, far too much information to process efficiently. And it’s not necessary. Instead, identification relies on comparing repetitive sequences which can be found at various chromosomal locations, or “loci.” These “short tandem repeats,” or STR’s, can take various forms.

For example, at locus CSF1PO (in chromosome 5) it’s always AGAT. Each locus actually has two STR sequences: one is the “allele” or gene variant contributed by the mother’s chromosome, and one is the allele contributed by the father’s chromosome. In this example, one of the two CSF1PO’s alleles has twelve AGAT repeats. According to population studies alleles at CSF1PO can have between six and sixteen AGAT repeats.

Wouldn’t there be many people who have the same number

of repeats at this locus?

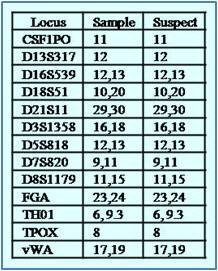

Yes. Numerous persons have the same alleles at one or more loci. But when one compares alleles at thirteen loci, the number required under the FBI’s CODIS system, the probability that a biological sample will be tied to an innocent person (the so-called “random match probability”) is infinitesimally small, far less than one over the population of the Earth.

This example demonstrates a perfect match at each of the thirteen loci used by CODIS. Repeat sizes are reported for both alleles. (If both parents contributed the same number of repeats only a single number appears.)

So this suspect must be the source of the DNA sample.

Yes, most likely, unless they have a twin. Analysts will testify that a match at thirteen loci establishes a positive identification. However, the statistics are less impressive when low amounts of DNA or degradation makes it impossible to type a biological sample at all thirteen loci. CODIS does accept DNA profiles from forensic samples with as few as ten loci, which also yield high match probabilities, but are not unique. Some State systems may allow fewer.

Does subjectivity ever intrude into DNA identification?

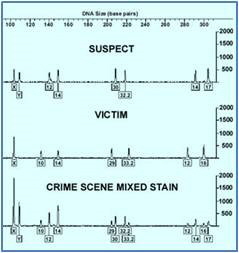

It can. When evidence DNA is from a single source there is general agreement on computing random match probabilities. But interpretation is more difficult when samples are mixed; for example, a rape with multiple assailants. Mixed DNA is like mixing names made with scrabble tiles. For each person you add to the mix, the number of possible names you can pull out soars, so excluding anyone becomes problematic.

Mixture electropherograms, the charts used to detect alleles, can become crowded with peaks, making contributors extremely difficult to distinguish. We know from laboratory studies that an allele may sometimes be undetectable because one contributor’s DNA is in a low concentration and a few alleles have “dropped out.” Other times an allele may be obscured by someone else’s peak. When two people touch an object, one profile might dominate while the other may be completely absent. These difficulties and differences in protocols can lead labs to vary a billion-fold when estimating mixed-sample match probabilities from the same data.

And there’s another problem that becomes more of an issue with mixtures – the possibility of bias. Most labs train analysts not to look at suspect profiles before performing mixture analysis. However, since it’s always easier to traverse a maze backwards, the goal of true blind testing is frequently violated. Analysts who have suspect DNA profiles on hand are susceptible to bias and could be less likely to exclude a suspect in a complicated mixture. Also, while most lab protocols require a second, independent analysis, the second analyst is often a close colleague who may have access to the first analyst’s conclusions.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

What suggestions do you have for the future?

There needs to be a lot more study and experimentation with mixed-sample DNA. There’s no accepted standard for interpreting mixed samples, nor is there general agreement among experts as to when to exclude a suspect. Studies by independent researchers are also needed to help labs avoid bias, and enforcement of true independent analysis should be instituted. Defense lawyers and prosecutors are by and large uninformed about these issues, and courts tend to leave it to jurors to work out any apparent contradictions. It’s an irony that the technique that’s been so useful in convicting the guilty and freeing the innocent may wind up leading to wrongful convictions in mixture cases, especially those with very low amounts of starting DNA.

UPDATES

12/25/20 Developments in “probabilistic genotyping,” which uses software-driven algorithms to estimate a mathematical likelihood that DNA profiles match, are helping analysts deal with complex mixtures. However, not every profile has enough data, and some samples still prove too complex.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Is Your Uncle a Serial Killer? The Killers of L.A.

|