|

Posted 12/18/23

ARE CIVILIANS TOO EASY ON THE POLICE? (II)

Exonerated of murder, but not yet done

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. On Wednesday evening, December 6, one week after opening arguments and “less than two hours” after getting the case, a Prince George’s County, Maryland criminal jury acquitted suspended police officer Michael A. Owen, Jr. of all charges over the January 27, 2020 shooting death of William Howard Green (right-side photo). Owen (left side photo) had been in custody since one day after the shooting. And as the first Prince George’s officer to ever be charged with an on-duty murder, he was denied bail and wound up spending nearly four years behind bars awaiting trial. (Shockingly, he may have another one coming. We’ll get to that later.)

Unlike the gnarly circumstances (i.e., pretextual traffic stops) that underlie many of our posts, the tragic encounter with Mr. Green began as an episode of so-called “routine” policing. Owen was dispatched to the scene of a major traffic wreck. Mr. Green’s car had gone out of control, struck several other vehicles and “crashed into a tree”. Passers-by found him unconscious and called police. And when officers arrived they quickly observed that Mr. Green was deeply intoxicated. As Owen’s prosecutor conceded, Mr. Green “did cause several accidents and was high on PCP or at least had PCP in their system”.

Click here for the complete collection of compliance and force essays

After the officers searched and handcuffed Mr. Green (natch, behind his back) they placed him in the front passenger seat of Owen’s cruiser. Mr. Owen’s colleague stepped away to interact with witnesses and victims. Owen took a seat behind the wheel to watch over Mr. Green and await the arrival of a drug testing unit. Its arrival, though, was delayed. After about twenty minutes Mr. Green said he had to urinate, and the ex-officer’s response supposedly agitated him. Mr. Green reportedly turned violent and a struggle ensued. According to the cop, his prisoner had somehow gotten hold of a gun, and Owen grabbed it and fired in self-defense. Owen insists that he was startled to discover that the pistol was, in fact, his own duty gun. It was fired seven times. Its first shot apparently went astray. But the six bullets that followed struck Mr. Green and inflicted fatal wounds.

Alas, then-cop Owen wasn’t assigned a bodycam. None of what happened was captured on video, so all we “know” is what he said. Instead of just relying on media accounts, let’s turn to his courtroom testimony. It took place on Monday, December 4 (we paid the court reporter for the transcript).

DIRECT EXAMINATION BY OWEN’S LAWYER

Owen testified that he was dispatched to an accident with injuries. On arrival a witness pointed to the vehicle that caused the collision. As he and Corporal Villaflor approached the car they observed Mr. Green inside, “slumped against like the driver side window” and “nonresponsive.” Mr. Green slowly awakened when his partner rubbed his sternum. They physically hauled Mr. Green out of his car and patted him down. It wasn’t a “search”; they didn’t reach into his pockets. That’s when Owen told his partner “I smell PCP.”

Owen feared that Mr. Green could turn violent, so he was handcuffed behind his back. Mr. Green noticeably reacted. “Mr. Green is not resisting per se but he's tensing up. He's pulling away. And so we kind of have to use like joint manipulation just to get him in handcuffs.” Owen then fetched his car and his partner left. Owen placed Mr. Green in the front passenger seat. Policy required it for “single-officer” cars that lack a cage. He then backed the cruiser into a parking space to get it out of the way.

Owen spent the next twenty minutes “doing paperwork on my computer” while “keeping an eye on Mr. Green”. He occasionally asked questions. At first Mr. Green was mostly unresponsive. He dozed on and off. But then things turned in a decidedly negative direction.

Owen: “...as he began to become more lucid…his behavior deteriorates. He starts using vulgar language and begins to tell me he does what he wants, he wants to go to the bathroom, which my response is give me few minutes, sir, and I'll get you to a bathroom as soon as I can. But he becomes more and more agitated as time goes on…”

According to Owen, Mr. Green moved his hands from the side and placed them “behind his back.” He then “begins to reach into the small of his back and it looks like he’s manipulating something”.

Owen: “I grabbed his hands and pulled them back out from behind him and told him don’t do that, leave your hands to the side.”

Q: “And did he comply with that request?”

Owen: “For about like five seconds… and then he goes back and continues to look like he's manipulating something. At this point he actually raises up off his seat, kind of presses feet against the floor board.”

Owen said he reached for the in-car microphone to call for help. But Mr. Green used his left leg to knock it out of his hands.

Owen: “…immediately after that he began thrashing about. I’m still trying to control his hands. And he’s throwing his body weight around, trying to kind of head-butt me and stuff. I’m trying to control him as best I can, but it’s very obvious that he has like superhuman strength.”

Owen said he tried to apply “pain compliance” by twisting the handcuffs, but it didn’t work.

Owen: “…So he's twisting the upper part of his body. His legs are flailing. He's moving from one side to the other. He's generally trying to get away from me…He was calling me all types of names, bitches, pussy ass nigger was one of them…”

And when Owen tried to use his personal radio, Mr. Green “escapes my grasp”.

Owen: “…he hits me very forcefully with all of his body weight pressing me, really slamming me into the B pillar driver’s side of the car… causing me excruciating pain in my torso section.”

Owen then heard “a hollow metallic thud”.

Owen: “I recognized -- I know it’s a gun hitting the center console. No doubt about that in my mind. I fight through the pain and look down in the center console and there is a gun… Mr. Green had his hands on the gun, saw that the gun was pointed at me…”

Owen said that he didn’t run off because he could have been shot in the back. So he grabbed at the gun.

Owen: “We're struggling over it. He's extremely strong…I reached down, grabbed the gun, struggling over it with Mr. Green, trying to, one, you know, turn the muzzle away from me, and, two, get it from him in general…”

Q: “Okay. And what happens next?”

Owen: “As we’re fighting over the gun, a shot is fired…At that point I was able to retrieve the gun and I fired a quick succession of rounds, stopped, re-accessed Mr. Green's behavior at this point, and then was able to safely exit the car based off of his behavior…”

Q: “Okay. And what observations did you make to lead you to the conclusion that he was no longer a threat to you?”

Owen: “He wasn’t moving anymore.”

According to Owen, he didn’t realize that it was his own gun.

Owen: “I knew that it was a black handgun. During that entire interaction I don’t -- I’m not processing these very minute details. And so I look at the gun -- and again this happens extremely quickly -- but I look at the gun, recognize that it is a Smith and Wesson. And when and I look down at my holster, and my jaw just dropped.”

Owen said that Mr. Green’s hands on the gun eliminated less-lethal alternatives, such as a Taser.

Q: “So what I’m talking to you about is when saw the gun, when you looked at it and saw Mr. Green's hand on the gun, was anything in the continuum use of force a possibility aside from deadly force?”

Owen: “No, sir.”

Q: “And is that why you exercised deadly force in this case?”

Owen: “Yes.”

CROSS-EXAMINATION BY STATE’S ATTORNEY

Owen agreed that the original pat-down should have detected a concealed weapon. He said that he again patted down Mr. Green before placing him in his car, but said it wasn’t as thorough. Owen also testified that he did not feel his gun leave its holster. And he insisted that while Mr. Green was handcuffed behind his back, that’s not where his hands wound up:

Owen: “I hear [the gun] hit the center console. When I looked back toward Mr. Green he is no longer making contact with me. He's got his hand on the gun.”

Q: “With his hands still behind his back?”

Owen: “His hands are not behind his back, they're off to the side, he's handcuffed behind his back, but his hands are off to the side and kind of turning a little bit away from me…He's got the gun pointed at me with his hands.”

Owen rejected the prosecutor’s implied criticism of his gunfire.

Q: “After firing shot number two, did you reassess the threat?”

Owen: “Sir, these shots are happening extremely quickly. I think we heard witnesses testimony say sound like a machine gun. So –"

Q: “You have to pull the trigger intentionally each time, correct?”

Owen: “Yes, but all of these happened together. There is not -- extremely quickly. There is not a lot of time for -- I think like I’m going to die, sir…”

But when pressed about why he didn’t get out of the car after the first shot, Owen said that Mr. Green might have had another gun and shot him in the back.

Q: “So, when after -- once you got control of the gun, you fired the other six shots because you believed that he still was in possession of a gun, correct?”

Owen: “Yes.”

Q: “And ultimately you realized that he didn't -- there was no other gun in the vehicle, other than your gun, correct?”

Owen: “I believe that if I turned to exit the vehicle that it was possible that Mr. Green, because of his movements, had another weapon and might use it, and might use it against me.”

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION BY OWEN’S LAWYER

Owen’s lawyer promptly honed in on the basics:

Q: “When you looked and saw the gun on the center console with Mr. Green’s hand on it, pointing at you, what did you think?”

Owen: “I thought I was going to die.”

Q: “Is that why you reacted the way you reacted?”

Owen: “Yes.”

STATE’S ATTORNEY: “I have no officer questions.”

JUDGE: “You may step down.”

Prince George’s County State’s Attorney Aisha Braveboy disparaged the suspended officer’s testimony as “outrageous” and “certainly implausible”. Naturally, she was gravely disappointed by the verdict:

We believe that Cpl. Owen committed a crime that night, and he did in fact murder William Green. However, the burden is on the state, and it is a very high burden. There were only two people in the vehicle that night that could tell us what happened, and unfortunately one of them is no longer with us.

Throughout the trial, she battled the notion that Owen had faced a real threat. So what drove him to kill? In her closing remarks, she suggested that the cop got mad because Mr. Green urinated in his patrol car. That’s admittedly a big leap. Still, she needed something. Local residents (even some judges) had long displayed a reluctance to sanction cops who tangled with misbehaving souls. For example, in 2005 jurors acquitted a Prince George’s cop of assaulting a suspect who had stolen a van “at gunpoint,” then crashed it when pursued. Video depicts the officer (like Owen, a corporal) repeatedly kneeing and whacking the man even after he’s handcuffed and on the ground. State’s attorney Glenn Ivey, who had two years on the job, was disappointed in the outcome. Still, as he well knew, his predecessor had prosecuted eleven officers for misconduct in eight years but failed to gain a single conviction.

Natch, it’s not just Prince George’s. In an unforgettable 2015 episode, Baltimore police arrested Freddie Gray. His behavior had drawn the attention of bicycle cops, and in the ensuing struggle they found a switchblade in his pockets. Mr. Gray was arrested, hog-tied and shoved into a paddy wagon. Alas, no one had belted him into a seat, and he suffered fatal injuries while bouncing around during transport. Six officers (including a Lieutenant) were charged with murder and manslaughter. Each was acquitted, and the Feds refused to bring charges. Natch, it’s not just Prince George’s. In an unforgettable 2015 episode, Baltimore police arrested Freddie Gray. His behavior had drawn the attention of bicycle cops, and in the ensuing struggle they found a switchblade in his pockets. Mr. Gray was arrested, hog-tied and shoved into a paddy wagon. Alas, no one had belted him into a seat, and he suffered fatal injuries while bouncing around during transport. Six officers (including a Lieutenant) were charged with murder and manslaughter. Each was acquitted, and the Feds refused to bring charges.

Indeed, as we reported in Part I and its updates, citizens are reluctant to convict cops who tangle with palpably naughty characters. That’s frustrated the progressive, reform-minded prosecutors who came aboard post-George Floyd. Last year, the office of then-San Francisco D.A. Chesa Boudin (he’s since been recalled for being too soft on crime) prosecuted “the first excessive-force trial for an on-duty officer in the city’s history.” And as usual, jurors returned a “not guilty” verdict. In your writer’s own stomping grounds, a jury recently acquitted two former Long Beach, Calif. police officers of perjury for accusing the wrong parolee (two were detained) of possessing a gun. In 2018, when the stop occurred, the then-D.A. chalked the cops’ faux-pas as an honest (if unfortunate) mistake. But when reformist D.A. George Gascon took the helm in 2020, things changed.

Cops know that citizens are likely to grant them a “pass”. That’s why LAPD’s rank-and-file championed the 2019 city ordinance that currently lets officers choose all-civilian panels to rule over the Chief’s decisions to fire. Naturally, Chief Michel Moore thinks that was a very bad move. Here’s an extract from his December 7, 2022 memorandum to the Police Commission:

The Department has observed that all-civilian Boards are resulting in an increased frequency in which sworn employees who have committed serious misconduct are not being removed from their positions. Similarly, all-civilian Boards are proving substantially more lenient reducing every recommended penalty in each Board completed this year.

Would it have helped Owen’s prosecutor if she could have brought up his prior disciplinary record? According to the Washington Post, his ten years on the job were sprinkled with controversy. Here’s a summary:

- November 11, 2010: Shortly after graduating from the academy, Owen exchanged gunfire with a would-be mugger while off-duty. No one was struck.

- December 17, 2011: Owen shot and killed an apparently intoxicated man who was lying on the grass and allegedly pointed a gun. A loaded gun was found, and the man’s past included firearms charges. Owen applied for and received State compensation for a “permanent partial disability” supposedly brought on by this encounter. He apparently continued receiving treatment for PTSD throughout his career.

- 2013: Owen didn’t appear in court for the arraignment of a “suspicious” man with whom he tangled. Charges against the suspect were dismissed in exchange for dropping a lawsuit that claimed Owen assaulted him.

- 2016: Charges in two traffic-related cases were dismissed because Owen failed to show for court. In the first, a woman accused him of grabbing her neck during an argument. In the other, an off-duty college cop disputed that he became combative. These no-shows led Owen to be flagged in the agency’s “early warning” system.

- July 13, 2019: Owen’s alleged use of brute force on an uncooperative suspect apparently led prosecutors to drop charges against the man.

- July 31, 2019: Owen accidentally discharged his gun while struggling with a motorcycle thief (no one was struck.) Owen had to take “judgment enhancing shooting training” and meet with the department psychologist. He was again flagged in the early warning system.

And there was that lawsuit. On Monday, September 28, 2020, eight months after Mr. Green’s death and nearly three years before Owen was tried, Prince George’s County settled with the victim’s family for $20 million. They had been represented by the same Baltimore law firm (Murphy Falcon & Murphy) that had obtained a $6-million-plus payout for the death of Freddie Gray.

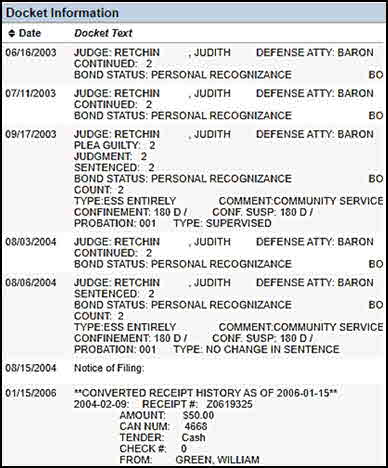

No dice there either. As far as the trial judge was concerned, it was all about what happened on that Monday night in 2020. Everything else was off-limits. Still, prosecutor Braveboy did get a break. While neither the officer’s disciplinary history nor the survivor lawsuit could come in, neither would his alleged victim’s criminal record. And one did exist. According to D.C.’s WUSA9, Mr. Green had been arrested by D.C. police in 2003 for “buying a single PCP-laced cigarette”. Our online examination of court files (see image) revealed that “William Green” was charged with felony possession of PCP on May 30, 2003 (case no. “2003 FEL 003162”). Mr. Green pled guilty that September and drew probation. Apparently things didn’t work out: there was a re-do in 2004, but probation was re-imposed. D.C.’s criminal case website has many other entries for a “William Green”. However, there are no birthdates or other means to readily determine whether any are about our Mr. Green. As for Prince George’s County, only civil cases are accessible online. So our tools for probing the victim’s record were limited. No dice there either. As far as the trial judge was concerned, it was all about what happened on that Monday night in 2020. Everything else was off-limits. Still, prosecutor Braveboy did get a break. While neither the officer’s disciplinary history nor the survivor lawsuit could come in, neither would his alleged victim’s criminal record. And one did exist. According to D.C.’s WUSA9, Mr. Green had been arrested by D.C. police in 2003 for “buying a single PCP-laced cigarette”. Our online examination of court files (see image) revealed that “William Green” was charged with felony possession of PCP on May 30, 2003 (case no. “2003 FEL 003162”). Mr. Green pled guilty that September and drew probation. Apparently things didn’t work out: there was a re-do in 2004, but probation was re-imposed. D.C.’s criminal case website has many other entries for a “William Green”. However, there are no birthdates or other means to readily determine whether any are about our Mr. Green. As for Prince George’s County, only civil cases are accessible online. So our tools for probing the victim’s record were limited.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

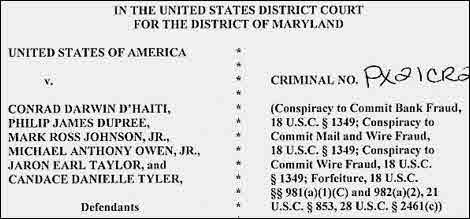

Still, the suspended cop remains suspended. And it’s over allegations that seem unlikely to draw nearly as much sympathy. In August 2021 the Feds indicted Owen and five other D.C.-area cops on conspiracy charges. According to DOJ, they participated in an  elaborate scheme to defraud insurance companies and financial institutions by falsely reporting the theft of vehicles, debit cards and funds from bank accounts. Owen recently pled not guilty and was released pending trial. This case, though, was also off-limits for prosecutor Braveboy. After all, imagine how it might have biased the jury’s opinion of the accused’s integrity and truthfulness. elaborate scheme to defraud insurance companies and financial institutions by falsely reporting the theft of vehicles, debit cards and funds from bank accounts. Owen recently pled not guilty and was released pending trial. This case, though, was also off-limits for prosecutor Braveboy. After all, imagine how it might have biased the jury’s opinion of the accused’s integrity and truthfulness.

Just imagine.

Whether civilians really do “go too easy” on police promises to be a never-ending debate. As we “go to press” Washington state jurors are deliberating the fate of three Tacoma police officers who were charged with murder and manslaughter in the death of Manuel Ellis. During a nine-week trial, officers Christopher Burbank, Matthew Collins and Timothy Rankine were accused of needlessly pummeling, choking and Tasering Manuel Ellis during a seemingly minor encounter and ignoring his protests that he couldn’t breathe. Indeed, the Coroner attributed his demise to oxygen deprivation caused by forcible restraint. But the defense insisted that Ellis, a meth user, “created his own death”:

This is a situation where [Ellis] created his own death. It was his behavior that forced the officers to use force against him.”

That was, in effect, Owen’s defense. Will it work for Tacoma’s cops? Check the update!

UPDATES (scroll)

3/21/25 A decade ago two LAPD officers tussled with a disorderly 29-year old homeless man. During the encounter officer Clifford Proctor drew his gun and shot Brendon Glenn dead. Video disputed the officer’s claim that he fired because Glenn went for his gun. Police Chief Charlie Beck recommended Proctor be charged, and Proctor resigned. But then-D.A. Jackie Lacey declined to prosecute. Her replacement, reform-minded George Gascon, had a special prosecutor re-examine four police shootings during his predecessor’s watch. And Proctor was reportedly just charged with the killing.

4/17/24 After the foreperson announced the panel was deadlocked 7-5, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge declared a mistrial in the case against ex-schools cop Eddie Gonzalez. Charged with 2nd. degree murder for shooting and killing a passenger in a car that he approached after an altercation on a nearby campus, Gonzalez insisted that he fired because the car’s sudden movement placed him in danger. But that’s been strongly disputed. According to the foreman, the holdouts favored a manslaughter conviction. A lawsuit against the school district was settled for $13 million last year. A retrial is pending.

1/22/24 Another criminal jury hangs in a cop’s trial. Former LAPD cop Salvador Sanchez was off duty in 2020 when he got knocked to the ground. But his assailant was twenty feet away when Sanchez fired, killing the mentally troubled, 32-year old man. Local D.A.’s refused to charge Sanchez, so the California A.G. stepped in. Whether Sanchez will be retried for voluntary manslaughter and assault with a firearm is to be decided. LAPD fired him and a Federal jury awarded the slain man’s family $17 million.

1/18/24 In May 2021 the Washington State A.G. charged Tacoma cops Matthew Collins, Christopher Burbank and “Timmy” Rankine with crimes ranging from 2nd. degree murder to 1st. degree manslaughter. In a 2020 encounter they allegedly pressed down on Manuel Ellis with such force that he stopped breathing. But at the end of their recent trial (it lasted over two months) jurors apparently accepted the defense argument that Mr. Ellis died from a lethal does of meth and an existing heart condition, and found the officers not guilty on every count. Each has agreed to accept $500,000 to resign from the force.

1/2/24 “Police Officers Are Charged With Crimes, but Are Juries Convicting?”, a feature story in the New York Times, reports that George Floyd’s murder set off a “national movement” against brutal policing. But while prosecutors seem more wiling to charge cops with crimes, jury verdicts have been “a mixed bag” that includes acquittals and a mistrial. Citizens may have proven reluctant to challenge “split-second” decisions made under great stress. And their view of the police role has also been in flux.

12/22/23 A jury acquitted Tacoma police officers Christopher Burbank, Matthew Collins and Timothy Rankine of all charges in the 2020 death of Manuel Ellis. They had been accused of needlessly beating and choking Mr. Ellis during an encounter supposedly provoked by his odd behavior. But they claimed that his meth use was to blame. Mr. Ellis’ prior arrests were brought in during the trial, and this is thought to have influenced the jurors. Wikipedia entry

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Craft of Policing special topic

Another Victim: the Craft of Policing Are Civilians Too Easy on the Police? (I)

Intended or not, a Very Rough Ride A Stitch in Time

Posted 9/21/23

CONFIRMATION BIAS CAN BE LETHAL

Why did a “routine” traffic stop cost a Philadelphia man’s life?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. On August 14, two Philadelphia police officers assigned to the 24th. police district were on routine patrol when they observed a car “being driven erratically” in the area of “B” Street and Westmoreland. According to then-police commissioner Danielle Outlaw (she’s since announced her resignation) Officer Mark Dial, the passenger, and his partner, the driver, asked dispatchers whether that vehicle had recently raised suspicion (it hadn’t).

Officer Dial and his partner followed the car for about a half-mile as it drove down Westmoreland, turned left onto Lee St., and left again at Willard, a one-way street that runs in the opposite direction. After going the wrong way for a short distance it pulled to the left curb and parked.

Click here for the complete collection of compliance and force essays

That’s where PPD’s initial account – that the vehicle’s driver and sole occupant, 27-year old Eddie Irizarry, promptly jumped out wielding a knife – apparently went off the rails. As Ms. Outlaw acknowledged two days after the tragedy, Mr. Irizarry never stepped out of the car. Instead, Officer Mark Dial shot and killed him while he remained seated behind the wheel, with the windows rolled up. And yes, the encounter was captured by a stationary camera. We clipped this sequence of images from the video, which was posted online.

Images 1 & 2 depict Mr. Irizarry’s arrival (again, his car is going the wrong way). He quickly pulled to the curb, ran over a traffic cone, then backed in, blocking a parked SUV (3). His car stopped moving at 12:24:10. The police car arrived five seconds later (3-4). Officer Dial exited the passenger side at 12:24:16. He immediately walked around the front of Mr. Irizarry’s car, reportedly yelling “show me your hands!” and “I will f***ing shoot you!” (4 & 5). Officer Dial began firing through the driver side window, which was rolled up, at 12:24:22 (6). That’s six seconds later. And he kept shooting as he walked away (note the shattered glass) (7). His final, final, sixth round was fired at 12:24:24, eight seconds after he got out of the police car. Officer Dial then went to the passenger side of Mr. Irizarry’s car, and his partner came to the driver’s side and opened the door (8). They placed Mr. Irizarry in the police car and drove him to the hospital. But it was too late.

Here’s the sequence using clips from Officer Dial’s bodycam:

Image 1 shows the police car’s arrival. Image 2 depicts Officer Dial walking to Mr. Irizarry’s car. Images 3 & 4 show him as he begins shooting, and Image 5 as he continues firing while walking away.

What do we know about Mr. Irizarry? His family and their lawyers contend that he suffered from chronic “mental problems”, including schizophrenia. These issues, however, apparently didn’t prompt any past police intervention. According to lawyer Shaka Johnson, Mr. Irizarry “has never been arrested a day in his life…He's never seen handcuffs, the inside of a jail cell. Ever in 27 years. Never had a negative encounter with police.” We confirmed through What do we know about Mr. Irizarry? His family and their lawyers contend that he suffered from chronic “mental problems”, including schizophrenia. These issues, however, apparently didn’t prompt any past police intervention. According to lawyer Shaka Johnson, Mr. Irizarry “has never been arrested a day in his life…He's never seen handcuffs, the inside of a jail cell. Ever in 27 years. Never had a negative encounter with police.” We confirmed through  Pennsylvania’s official portal that Mr. Irizarry has no State record of a criminal arrest. However, our review of Philadelphia municipal court records turned up a 2018 case in which Mr. Irizarry pled guilty to disobeying a traffic control device (Docket #CP-51-SA-0000205-2018). While that’s no great shakes, it seems consistent with his allegedly erratic driving, including making that improper left turn onto Willard St. (see right). Pennsylvania’s official portal that Mr. Irizarry has no State record of a criminal arrest. However, our review of Philadelphia municipal court records turned up a 2018 case in which Mr. Irizarry pled guilty to disobeying a traffic control device (Docket #CP-51-SA-0000205-2018). While that’s no great shakes, it seems consistent with his allegedly erratic driving, including making that improper left turn onto Willard St. (see right).

Still, considering that Mr. Irizarry remained in his car, and just how quickly Officer Dial opened fire, there may seem to be little reason to probe further. Most importantly, there’s no indication that Mr. Irizarry had a gun. We don’t have access to the bodycam video of the police car’s driver. But according to the lawyers for Mr. Irizarry’s family, who apparently do, Officer Dial’s partner quickly announced “he’s got a knife.” That supposedly spurred Officer Dial to order Mr. Irizarry to “drop the knife.” (Police commissioner Outlaw’s account substituted the word “weapon” for “knife”. Implications-wise, that’s a big difference.) And when Officer Dial took his brief glimpse through the driver-side window – which was rolled up – he supposedly observed Mr. Irizarry “holding a small, open folding knife against his thigh.” It turns out that there were two knives in the car, and both were in plain view. Officials described one as a “serrated folding knife” and the other as “some type of kitchen knife” (the family’s lawyers said that Mr. Irizarry had a “pocket knife” he used for work.)

Clearly, neither dodgy driving nor having knives justifies killing. These behaviors may, however, provide some insight into where Mr. Irizarry was “at”. Perhaps the same applies to Officer Dial. Our essays are replete with chaotic episodes where cops inappropriately use lethal force. Sometimes a citizen waved a knife. Sometimes cops “saw” a gun that wasn’t there. Sometimes a troubled, uncompliant soul – Ta’Kiya Young comes to mind – stepped on the gas at the wrong time. On occasion, the justification for responding with gunfire was clearly lacking. For a recent (and most depressing) example check out “San Antonio Blues.” It’s about three cops who fired through the window of an apartment, killing a mentally troubled woman who threatened them with a hammer. Bodycam videos created such a compelling narrative that the officers were promptly arrested for murder (click here for a narrated video compilation).

Ditto, Officer Dial. Thanks to the neighborhood camera and his own bodycam, what happened doesn’t really seem at issue. He’s been charged with murder and is out on $500,000 bail. A preliminary hearing is set for September 26. But that’s not quite the “end of the story”. According to his lawyer, video (we assume, from his partner’s bodycam, which we haven’t seen) “demonstrates completely that Officer Dial got out of his car, ordered him to show his hands, and then heard ‘gun.’ You can hear it on the video. He then saw an individual pointing what he thought was a gun right in his face.”

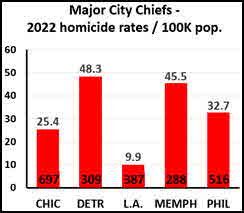

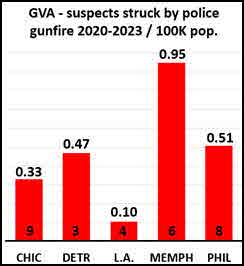

We’ll have more to say about Officer Dial’s decision-making later. For now, we as usual turn to place. To begin with, he and his partner worked in a particularly violent metropolitan area. Check out our comparo on the left, which was prepared from data published by the Major City Chiefs. Philadelphia’s 2022 murder rate (rates on top, number of incidents below) was more than three times L.A.’s. It even surpassed the rate of notoriously violence-stricken Chicago! We’ll have more to say about Officer Dial’s decision-making later. For now, we as usual turn to place. To begin with, he and his partner worked in a particularly violent metropolitan area. Check out our comparo on the left, which was prepared from data published by the Major City Chiefs. Philadelphia’s 2022 murder rate (rates on top, number of incidents below) was more than three times L.A.’s. It even surpassed the rate of notoriously violence-stricken Chicago!

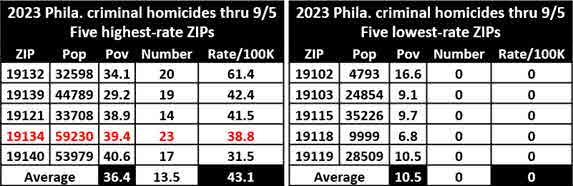

Still, as we emphasize in our “Neighborhoods” posts, when it comes to making inferences from statistics, citizens don’t live – and cops don’t toil – in aggregates. What really matters are neighborhoods. Let’s examine Philly’s:

Officer Dial was assigned to Philadelphia PD’s 24th. District, and the encounter, from beginning to end, took place within its primary ZIP, 19134. We downloaded and ZIP-coded January 1 – September 5, 2023 homicide data from the city’s official website and obtained population and poverty numbers for each of Philadelphia’s 35 residential ZIP’s from the Census. With a deplorable 39.4 percent of its citizens in poverty (U.S. is 12.6 percent overall), ZIP 19134 (it’s highlighted in red) was the city’s third-poorest. And with a murder rate of 39.4 per 100,000 population, it was its fourth most lethal.

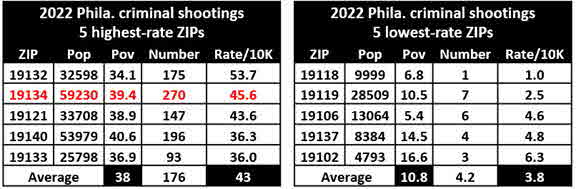

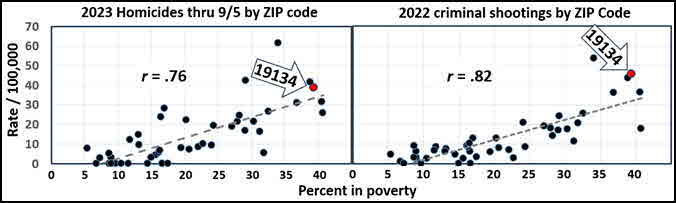

Violence isn’t only measured by murder. CBS collected data about criminal shootings in Philadelphia in 2022, and we ZIP-coded their locations. Here’s how that can of worms turned out:

ZIP Code 19134 (highlighted in red) comes in second-worst out of thirty-five. That’s decidedly not something to brag about. Neither is the disquieting fact that, as we chronically harp in our “Neighborhood” posts, poverty and violence are virtually in lockstep. Check out the “r” (correlation) statistics on these graphs:

Correlations can range from zero, meaning no association between variables (i.e., poverty and crime), to one, meaning a perfect, lock-step relationship. With an r of “plus” .76, Philly’s poverty and murder rates are, statistically speaking, very closely linked. Ditto, poverty and criminal shootings. In fact, at r=.82, that measure comes tantalizingly close to perfection. Of the lousy kind.

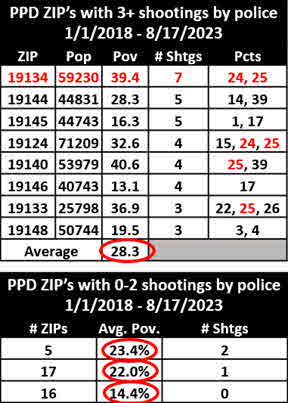

Let’s look at officer-involved shootings. We downloaded data from the Gun Violence Archive on suspects struck by police gunfire in our five cities between 2020-2023. Our bar graph on the left (rates on top, number of incidents below) places Philadelphia in the unenviable position of Let’s look at officer-involved shootings. We downloaded data from the Gun Violence Archive on suspects struck by police gunfire in our five cities between 2020-2023. Our bar graph on the left (rates on top, number of incidents below) places Philadelphia in the unenviable position of  surpassing chronically-beset Chicago and Detroit in terms of police gunfire. We also obtained information about officer-involved shootings in Philadelphia between 2018-2023 from its police portal (see right). That revealed that ZIP 19134 (circled in red), where Eddie Irizarry suffered his fatal encounter, had the greatest number and, as well, the highest rate of shootings. ZIP 19134 is actually served by two precincts, 24 and 25, which are housed together. Their officers also handle areas within several other ZIP’s, and three of those (19124, 19140 and 19133) had a substantial number of shootings as well. And that unholy relationship between crime and poverty is clearly evident. Notice how average poverty across ZIP’s (circled in red) worsens as the number of police shootings increases from zero to one, then to two, and finally to three-plus. surpassing chronically-beset Chicago and Detroit in terms of police gunfire. We also obtained information about officer-involved shootings in Philadelphia between 2018-2023 from its police portal (see right). That revealed that ZIP 19134 (circled in red), where Eddie Irizarry suffered his fatal encounter, had the greatest number and, as well, the highest rate of shootings. ZIP 19134 is actually served by two precincts, 24 and 25, which are housed together. Their officers also handle areas within several other ZIP’s, and three of those (19124, 19140 and 19133) had a substantial number of shootings as well. And that unholy relationship between crime and poverty is clearly evident. Notice how average poverty across ZIP’s (circled in red) worsens as the number of police shootings increases from zero to one, then to two, and finally to three-plus.

Lethal blunders have befouled policing since time immemorial. Supposedly well-intentioned officers were being charged with murder long before the George Floyd imbroglio hardened public and prosecutorial attitudes towards the police. Consider, for example, the 2017 killing of Justine Ruszczyk, a well-meaning, middle-aged Minneapolis resident who unexpectedly walked up to the police car that responded to her 9-1-1 call. The officer who shot her wound up serving three years for manslaughter and third-degree murder.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Officer Dial had been a Philadelphia cop for five years. We otherwise know preciously little about him. What we do know is that he worked in an especially poor and violence-prone zone of a violence-beset city. “Working Scared” emphasized that officer personalities are shaped by their working environment. As its subtitle asserts, “fearful, ill-trained and poorly supervised cops” are indeed “tragedies waiting to happen.” Was Officer Dial’s workplace so beset will ill-behavior that it exerted an unholy influence on every citizen-officer encounter? That’s where “confirmation bias” comes in. It’s the normal human tendency – meaning everyone, not just cops – to interpret things in a way that reinforces their pre-existing biases and beliefs. Mr. Irizarry’s erratic driving and, particularly, his rejection of authority figures – he immediately rolled up his window – might have “confirmed” Officer Dial’s biases and badly distorted his decisions.

It might even explain why a cop “saw” a non-existent gun. That, of course, doesn’t excuse his behavior. Really, police officers are human. They’re also well-armed. Although they’re also supposedly carefully selected, well trained and closely supervised, some continue to impulsively react with gunfire. Why is that? Are those working in violence-beset areas particularly affected? Might instinctively drawing a gun when danger looms be partly to blame? Given the quirks of human nature, and not just those of the badge-wearing kind, avoiding interminable replays would require that police embark on a brutally honest, in-depth exploration of the underlying issues. We mean at every academy session, every command get-together, and, most importantly, every roll-call, from now until the cows really do come home.

UPDATES (scroll)

9/28/23 At the conclusion of a September 26 preliminary hearing, a Philadelphia municipal court judge dismissed all charges against ex-officer Mark Dial in the killing of Eddie Irizarry. Her finding of “a lack of evidence” was bitterly criticized by the D.A. and, as well, by Irizarry’s family. Each charge, from 1st. degree murder on, was promptly refiled and a “motions hearing” (to be handled by a different judge) was set for October 25. Dial, who was being held without bail, was released.

9/22/23 Philadelphia police officer Mark Dial, who shot and killed Eddie Irizarry on August 14, was charged with murder and released on $500,000 bail on September 8. But prosecutors have argued that Dial’s liability to a 1st. degree murder conviction made him ineligible for pretrial release. On September 19 a judge agreed and remanded the suspended cop to jail at least until September 28, the date for his preliminary hearing, when a court will decide what charges Dial will actually face.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Craft of Policing special topic Neighborhoods special topic

Bringing a Gun to a Knife Fight Good News/Bad News San Antonio Blues

What’s Up With…Policing? Speed Kills Informed and Lethal Working Scared

Posted 8/24/23

WHAT COPS FACE

America’s violent atmosphere can distort officer decisions

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. In April 2023, following his return from tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, former Minnesota Army National Guardsman Jake Wallin was sworn in as a Fargo, North Dakota police officer. He was twenty-three years old. Three months later, on July 14, Officer Wallin was shot and killed, and officers Tyler Hawes and Andrew Dotas were wounded as they awaited a tow truck to remove a car involved in the collision to which they had been dispatched. (One of the involved drivers was also wounded.)

That vehicle, which sat in the middle of the road, was attended by a fourth officer, Zach Robinson. His bodycam soon captured the most disturbing images one could imagine. (Click here for bodycam-only and here for the press conference and narrated bodycam.) This sequence tracks the encounter:

As traffic peacefully streams by the disabled vehicle (1), the shooter, a 37-year old local man, unobtrusively sits behind the wheel of a car parked in an adjacent lot (2). Meanwhile Officers Wallin, Hawes and Dotas are on foot nearby, awaiting the tow truck (3). Bursts of gunfire suddenly shatter the calm. Bullets strike each of the three officers and one of the drivers involved in the collision (4). Their origin, an AR-15 type rifle wielded by Mohamad Barakat, the sole occupant of the parked car, is equipped with an accessory “binary trigger” that discharges a second round as pressure is released. That in effect transformed his already lethal rifle into a machinegun. Barakat had also brought more than enough ammunition – 1,800 rounds were found in his car – to engage in a protracted gunfight (our introductory image depicts the arsenal found in his home.)

Click here for the complete collection of compliance and force essays

That he didn’t was due to Officer Robinson’s heroic and highly talented efforts. Instantly jumping into the fray, he quickly spotted Barakat, then fired a string of shots using the disabled vehicle as a shield. Barakat, who had stepped out of his car, was fatally wounded (5-8). Officer Robinson then scrambled across the road and, bravely exposing himself to return gunfire, continued engaging the gunman as he crawled behind the vehicle to its driver’s side (9-11).

According to North Dakota Attorney General Drew Wrigley, Barakat was motivated by generalized feelings of hatred and picked on the crash scene “by happenstance”. His Internet searches over the years had featured keywords including “kill fast,” “explosive ammo,” “incendiary rounds,” “mass shooting events,” and, on the day preceding his attack, “area events where there are crowds.” That last search brought up Fargo’s downtown street fair, which was taking place nearby and was in its second day. Barakat had also expressed interest in the city’s “Red River Valley Fair,” a ten-day event that began July 7th.

Officer Robinson’s heroic response was absolutely correct. Alas, police shootings are often criticized, and often for good reason. A recent, noteworthy example is the August 5, 2023 fatal shooting by Denver police of Brandon Cole. This sequence tracks that encounter (click here for the video):

A 9-1-1 caller reported that Mr. Cole, 36, had pushed his wife off her wheelchair and attacked his teenage son. Two one-officer police cars responded (the images are from the second cop’s bodycam). They found the situation depicted in the first image. Mr. Cole’s wife was sitting on the curb. She asked for an ambulance but reportedly implored the officers “don’t pull your gun out on my husband, please.”

Mr. Cole, though, was aggressive from the start. He retrieved an object from his car, then walked towards the first officer, wielding what both cops thought was a knife (2-4). Although the second officer addressed Mr. Cole by his first name, he refused to stop. So while she covered things with her pistol, the first cop discharged his Taser (5-6). Alas, one of its probes apparently missed. Despite more orders to stop, Mr. Cole then went after the second cop, “knife” in hand (7-9). She fired as he reached the sidewalk, inflicting fatal wounds (10-11). Mr. Cole’s weapon (it’s circled in red in the last two images) turned out to be a black marker.

Mr. Cole’s pretend knife is reminiscent of an episode in Los Angeles last year. On July 18 a 9-1-1 caller reported that he was being bothered by an aggressive “dark-skinned guy with dreadlocks” to leave. But when he told the man to leave he replied “I'll leave when I want. You can leave”, then pulled out a black pistol. Here’s a sequence of images from an officer bodycam (click here for the original video, and here for our annotated version):

The first image portrays Jermaine Petit walking away from two officers who trail behind. A vehicle occupied by a Sergeant and another cop follow along (2). One of the cops (we don’t know which) draws close (3) and notices that Mr. Petit’s “pistol” (fourth image, circled in red) isn’t a firearm. It was a car part (see left). But in the rapidly evolving situation – watch the video and notice how quickly things moved along – the officer’s “it’s not a gun bro” comment (5) was apparently lost in translation. One of the officers on foot replied “huh?”, then ordered Mr. Cole to “drop it” (6). And as their quarry stepped into the street (7), a careless gesture likely provoked the sergeant in the car and an officer on foot to open fire (8). The first image portrays Jermaine Petit walking away from two officers who trail behind. A vehicle occupied by a Sergeant and another cop follow along (2). One of the cops (we don’t know which) draws close (3) and notices that Mr. Petit’s “pistol” (fourth image, circled in red) isn’t a firearm. It was a car part (see left). But in the rapidly evolving situation – watch the video and notice how quickly things moved along – the officer’s “it’s not a gun bro” comment (5) was apparently lost in translation. One of the officers on foot replied “huh?”, then ordered Mr. Cole to “drop it” (6). And as their quarry stepped into the street (7), a careless gesture likely provoked the sergeant in the car and an officer on foot to open fire (8).

Fortunately, Mr. Petit survived. He would get to celebrate his 40th. birthday.

We addressed pretend weapons five years ago in “There’s No Pretending a Gun”. Two weeks before that, “A Reason? Or Just an Excuse?” explored why officers occasionally mistake ordinary objects like cellphones for a gun. Two years before that there was “Working Scared”. Here’s an outtake:

What experienced cops well know, but for reasons of decorum rarely articulate, is that the real world isn’t the academy: on the mean streets officers must accept risks that instructors warn against, and doing so occasionally gets cops hurt or killed. Your blogger is unaware of any tolerable approach to policing a democratic society that resolves this dilemma, but if he learns of such a thing he will certainly pass it on.

Cops do get hurt and killed, and it’s more than “occasionally.” In our gun-beset land, preventives are few. Mohamad Barakat (legally) possessed a veritable arsenal. Even that “binary trigger” was legal. So when Mr. Barakat felt impelled to mount a terrorist attack, he instantly outgunned any ordinary cop on patrol.

Of course, cops well know that evildoers are apt to be better armed. Still, some officers are more skilled than others. Their personalities also vary. “Working Scared” emphasized that individual differences matter. But grab another look at the Denver and Los Angeles videos. Things were moving very quickly. Mr. Cole and Mr. Petit ignored officers’ supplications and commands, and those vaunted “de-escalation” practices weren’t an option. Both miscreants also clearly posed a threat to ordinary citizens. So that cure we once advanced – backing off and letting suspects go – wasn’t in the cards.

Neither Mr. Cole nor Mr. Petit presented a clear-cut armed threat. Neither did they co-operate with police. Mr. Cole, though, was at first dealt with more sternly.

- As a colleague covered him with her pistol, the first officer on scene fired his Taser, but, as we noted, unsuccessfully. Mr. Cole then redirected his attention to the other cop. Unfortunately, he closed in on her so quickly that even if she had a Taser, switching to it could have been too risky. So she shot him.

- Although they seemingly had several opportunities to do so, officers didn’t try to use a Taser against Mr. Petit. Perhaps the device was unavailable. His reported possession of a “pistol” may have also discouraged them from the distractions involved in deploying a non-lethal device.

One day ago, at a news conference in Fargo, Attorney General Merrick B. Garland expressed his heartfelt condolences over the murder of officer Jake Wallin and the wounding of his colleagues. He also praised officer Robinson, whose heroism “saved the community from what could have been a catastrophic result.” But the A.G. didn’t venture into correctives. As cops well know, in our gun-besotted land, remedies other than bravery are few.

So what is available?

- Assault weapons laws. Most recently, “Are We Helpless to Prevent Massacres?” conveyed our distressing conclusion that “lawmaking is not a solution.” That holds true in even supposedly “strong-law” states such as California (#1 in gun law strength per Giffords), where loopholes such as we mentioned in “Loopholes are (Still) Lethal” allow the sale and possession of highly lethal .223 caliber semi-automatic rifles like the weapon used by Barakat.

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. We’re unaware that the authorities had any advance notice that Mr. Cole or Mr. Petit were likely to lethally misbehave. On the other hand, Mohamad Barakat was well known. In 2021 an anonymous tip about his “mental state”, use of “threatening language” and gun possession led to his interview by Fargo detectives. Barakat “denied any ill-intentions.” But, like Mr. Cole and Mr. Petit, he lacked a criminal record prohibiting gun possession, and the matter was dropped. Then, last September, his home kitchen caught on fire. Firefighters came across a “significant amount” of ammunition, several assault rifles and two large propane cylinders that seemed out of place. But there was no follow-through, and his threatening Internet activities were apparently undiscovered until it was too late. Even had they been known, preventative efforts would have been difficult, as North Dakota lacks a “Red Flag” law that would enable a judge to order guns seized before disaster strikes.

- Non-lethal weapons. It’s not just Tasers anymore. There’s now BolaWrap, a gun-like device which shoots a long Kevlar cord that wraps around a target’s arms or legs, disabling without causing injury. LAPD, which touted its adoption four years ago, recently reported that patrol officers

successfully used it fourteen times during a one-year trial period. Still, to be truly effective, non-lethal means must be quickly deployed, perhaps far sooner than present rules allow. In a post-Floyd atmosphere that discourages the use of force, that presents a substantial hurdle for even the most seemingly benign devices. So while LAPD Chief Michel Moore bragged about BolaWrap’s deployment to officers who patrol Metro, the city’s transit system, Metro officials emphasized that its use is yet to be approved.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Of course, prevention is the best option. But as rookies quickly discover, ill-intended characters can easily arm themselves to the teeth. Moreover, cops are human. Their toolbox is limited. Given the highly conflicted situations they often face, and the lack of voluntary compliance they often experience, it’s no surprise that their lethal-force decisions will occasionally go astray. Last month we posted “San Antonio Blues,” which analyzed the police killing of a distraught, ill-behaving citizen whose “weapon” was a…hammer. This tragedy occurred in one of the beset city’s poorest, most violence-stricken neighborhoods. And as one might expect, that’s where police shootings were most frequent:

Does this let the three ex-cops “off the hook”? Certainly not. But to prevent endless replays, we must openly acknowledge that the disorder and lack of compliance common in poverty-stricken areas can poison officer decision-making and distort their response. However, the ultimate “fix” lies outside of policing. As we habitually preach in our Neighborhoods essays, a concerted effort to improve the socioeconomics of poor places is Job #1. Not-so-incidentally, that could also improve the dodgy behavior of some citizens. And good cops would find that most welcome!

In “On the One hand…But On the Other” and “Regulate. Don’t Obfuscate” we mentioned that the Floyd episode has fueled a toxic atmosphere, promoting a disengagement that can ill-serve the public and advancing rules that threaten to impair cops’ ability to protect themselves. But make rules all you wish. For real solutions, one must address the socioeconomic environment in which cops labor. There really is no third choice.

UPDATES (scroll)

4/28/25 As an LAPD helicopter whirred overhead, helping officers look for three males who fled from a hit-and-run, Jillian Lauren stepped into her backyard. She was brandishing a gun. Officers in an adjoining yard noticed. Peeking over a dividing fence, they repeatedly ordered her to put down the gun. But she didn’t. Gunfire soon broke out from both sides. Lauren was slightly wounded. Arrested for attempted murder, she claims to have been protecting herself from the bandits who prompted the police response. Police video compilation

10/9/23 LAPD, which adopted a lasso-like device for use in corralling recalcitrant persons, announced its intended deployment on the city’s transit system. But after citizens and a fellow Metro board member objected, Mayor Karen Bass nixed the idea. “Please, assure your grandson Wonder Woman will not be on Metro.” Still, police chief Michel Moore praised the results of a year-long pilot program and said that BolaWrap, a supposedly gentle alternative to batons and Tasers, will continue to be deployed.

8/25/23 Are cops needlessly spurring conflict through their choice of words and delivery? An academic study will scour bodycam videos of 1,000 officer-citizen encounters during a three-year period to identify the characteristics of successful interactions. Artificial intelligence will be used to select episodes where officers “cross the line” and to recommend solutions. Variables will include officer age and experience, citizen race, and the location of a stop.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Neighborhoods special topic Craft of Policing special topic

A Lethal Distraction Point of View Want Brotherly Love? Don’t Be Poor!

Are We Helpless to Prevent Massacres? Loopholes Are (Still) Lethal On the One Hand…

Backing Off Regulate. Don’t Obfuscate. There’s No Pretending a Gun A Reason?

Working Scared De-Escalation

Posted 7/20/23

SAN ANTONIO BLUES

Poverty – and what it brings – can impair the quality of policing

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. It’s a chilling scene. As bodycams grind on, three San Antonio, Texas police officers open fire on a distraught, mentally disturbed woman who aggressively approaches. With a hammer.

According to a press briefing by SAPD Chief William McManus, during the early morning hours of Friday, June 23 his officers responded to a report that a female resident of an apartment complex cut wires to its alarm system, setting it off and causing firefighters to respond. When police arrived and encountered her outside the complex, Melissa Perez, 46, ran back into her ground floor apartment and locked the door. And when an officer tried to speak with her through an open window, she threw a glass candle, striking him in the arm. A sergeant and two officers promptly relocated to the apartment’s rear patio and removed a window screen. From inside, Ms. Perez reacted by shattering the window glass with a hammer. One officer responded with gunfire. But Ms. Perez wasn’t struck, and she again went at the cops with the hammer. This time all three officers fired, inflicting mortal wounds.

Click here for the complete collection of compliance and force essays

What Ms. Perez didn’t have was a gun. What’s more, she and the officers remained on opposite sides of the apartment’s exterior wall throughout the encounter. According to the investigating detective’s criminal complaint, the woman San Antonio’s cops killed “did not pose an imminent threat of serious bodily injury or death when she was shot because the defendants had a wall, a window blocked by a television and a locked door between them.”

Amply corroborated by multiple bodycam videos (click here for SAPD’s narrated compilation), the circumstances were sufficiently damning to lead to the three officers’ arrest on murder charges that very same evening. And to their Chief’s highly contrite statement on the very next day. Ms. Perez’s killing added copious fuel to the long-troubled relationship between San Antonio’s cops and the citizens they serve and ostensibly protect. Here’s an outtake from the website of ACT 4 SA, a local group that argues for “a truly accountable, compassionate and transparent public safety system that works for everyone”:

These officers had been on the force ranging from 2-14 years…All are required to de-escalate according to SAPD policy, yet none acted accordingly. What kind of “training” is this? What type of “protection” is this? Why was the mental health unit not dispatched for this call? SAPD acted with neglect, foolishness, and violence that resulted in an unforgivable end to Melissa’s life.

As one would expect, a lawsuit’s been filed. It accuses officers, among other things, of ignoring that Ms. Perez, who was being treated for schizophrenia, was in an obvious “mental health crisis.” And while the cops could clearly see that Ms. Perez was alone and didn’t pose an immediate threat, they didn’t even try to de-escalate. Neither did their sergeant do his job. He failed to step in when an officer needlessly fired at Ms. Perez (supposedly discharging five rounds) but, even worse, began shooting as well. As one would expect, a lawsuit’s been filed. It accuses officers, among other things, of ignoring that Ms. Perez, who was being treated for schizophrenia, was in an obvious “mental health crisis.” And while the cops could clearly see that Ms. Perez was alone and didn’t pose an immediate threat, they didn’t even try to de-escalate. Neither did their sergeant do his job. He failed to step in when an officer needlessly fired at Ms. Perez (supposedly discharging five rounds) but, even worse, began shooting as well.

Ms. Perez wasn’t an unknown quantity. SAPD had reportedly taken her into protective custody in the past. Unfortunately, the city didn’t field a mental health team at night, and that’s when the tragedy occurred. There’s lots more in the civil complaint, and we’ll refer to it shortly. But when we learned of the incident, SAPD Chief McManus had already released the videos and delivered an exceedingly grim account that directly faulted his officers. Indeed, they had already been charged. So our attention instantly fell on them.

Each of the accused ex-cops (they’ve already been fired) is Hispanic, as was their victim. So this couldn’t be simply attributed to race or ethnicity. As your blogger can attest from personal experience, the personalities of law enforcement officers differ, sometimes dramatically, and some of these “differences” can profoundly affect – and, yes, even distort – how they respond to fraught situations. Here’s some self-plagiarism from “Working Scared”:

Prior posts have identified factors that can lead to the inappropriate use of lethal force. Some cops may be insufficiently risk-tolerant; others may be too impulsive. Poor tactics can leave little time to make an optimal decision. Less-than-lethal weapons may not be at hand, or officers may be unpracticed in their use. Cops may not know how to deal with the mentally ill, or may lack external supports for doing so. Dispatchers may fail to pass on crucial information, leaving cops guessing. And so on.

SAPD’s three supposedly trigger-happy cops include a fourteen-year veteran with the rank of Sergeant and two officers, one with five years on the job, the other with two. Records obtained by KSAT indicate that both the Sergeant and the five-year veteran (he’s the one who opened fire when Ms. Perez smashed the window) had substantial disciplinary histories:

- Sergeant ___ was suspended four times during the past five years. One suspension, for ten days, alleged that he “yelled profanities” at a person involved in a domestic quarrel. Two others, one for eight days, another for ten, were caused by his alleged failure to provide timely backup. And the most recent, for ten days, related to mishandling evidence.

- Officer ___ was suspended three times during his brief career. Once, for two days, for using profanity and damaging an inside door when chasing a disorderly man. Another suspension, for fifteen days, was levied because he let the parties involved in a traffic accident “settle” things between themselves although one was unlicensed and had active warrants. He was also once smacked with a 25-day suspension for trying to give a similar “break” to a Walmart shoplifter.

But according to the lawsuit, the Sergeant had suffered an additional suspension, in 2018, for failing to activate his body camera (p. 25). What went unpunished, though, was that during this episode he had pointed his gun at a distraught motorist, and supposedly without good reason. That, contend the plaintiffs, was par for the course:

The results of formal and informal policies have been that SAPD has created a culture of escalating mental health encounters that are unnecessary, objectively unreasonable and clearly excessive. This practice and culture is so common and well-settled as to constitute a custom that fairly represents municipal policy. (p. 12)

Former sergeant ___’s gun-pointing incident is apparently the only documented prior example of misuse of force by the three ex-cops. So to make the point that Ms. Perez’s lamentable treatment was “normal” by SAPD standards, the lawsuit offered ten examples of grave misuses of force by other SAPD cops (pp. 12-24). We recently mentioned one in an update to “When Must Cops Shoot? (II)”:

10/10/22 A San Antonio, Tx. police officer spotted a car that eluded him a day earlier parked at a MacDonald’s. So he walked up, opened the driver’s door and ordered its teen driver - he was munching a burger - to get out. But the youth promptly started the car and threw it into reverse. Its door bumped the cop, and he opened fire. Erik Cantu, 17, was badly wounded. And three days later, officer James Brennand, a rookie still on probation, was fired. Video 10/10/22 A San Antonio, Tx. police officer spotted a car that eluded him a day earlier parked at a MacDonald’s. So he walked up, opened the driver’s door and ordered its teen driver - he was munching a burger - to get out. But the youth promptly started the car and threw it into reverse. Its door bumped the cop, and he opened fire. Erik Cantu, 17, was badly wounded. And three days later, officer James Brennand, a rookie still on probation, was fired. Video

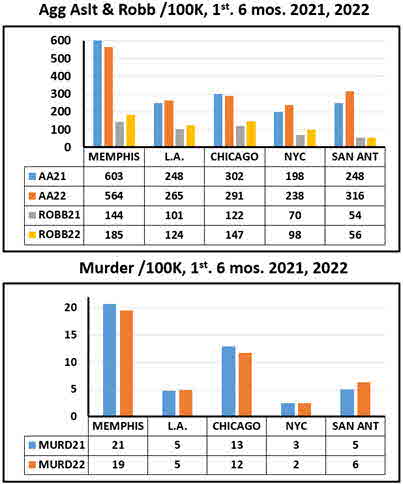

Most police officers manage to complete their careers without getting suspended even once. And certainly, without being charged with murder. But set individuals aside. Consider the environment in which they work. What is it that San Antonio officers actually face? Last September the Major City Chiefs Association, which represents the largest police departments in the U.S., released a report with violent crime data for its constituent cities for the first six months of 2021 and 2022. In “Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (II)” we used these numbers to compare violent crime in Memphis with our three “usual suspects” – L.A., Chicago and New York City. These charts extend that comparo to include San Antonio:

Note that the numbers are rates per 100,000 population, so they’re directly comparable. San Antonio’s rates are certainly not sterling, but nowhere near the abysmal numbers reported by Chicago and Memphis. As we’ve repeatedly cautioned, though, citywide statistics can obscure wide variances within. L.A.’s numbers look relatively favorable. But as “Good News/Bad News” recently reported, the January-June 2023 aggravated assault rate for its poverty-stricken Central area was sixteen times that of economically blessed Foothill Division.

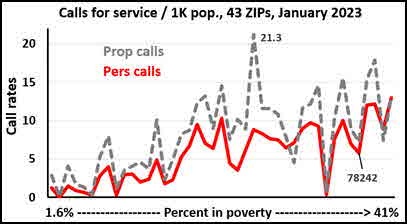

Ditto San Antonio. While its neighborhood crime rates can’t be readily compared (SAPD’s online data lacks crime location ZIP’s) the San Antonio city portal provides ZIP codes for police responses to citizen calls for service. Using Census ZIP poverty figures we coded “crimes against person” and “property crime” calls for service during January 2023 for forty-three San Antonio ZIP’s with populations over 10,000. This graph arranges ZIP’s by percent of citizens living in poverty:

During that month the 33,927 residents of ZIP 78242, where Ms. Perez resided, placed 196 persons-related calls and 245 property-related calls, producing per-1,000 rates of 5.8 and 7.2, respectively. While there are exceptions (one or two may have been caused by a reporting lapse), economically burdened ZIP’s tended to generate more calls for service, and especially for crimes against persons. For the statistically-minded, the “r” coefficient (it’s on a scale of zero to one, from no association to a perfect relationship) between poverty and persons calls is a compelling .84, and between poverty and property calls a lesser but still robust .66.

There were complications. About a dozen of these ZIP’s aren’t wholly within San Antonio, and calls for service to other agencies (say, the Sheriff) aren’t included. Considering only the twenty-two ZIP’s with populations over 10,000 that appear to be wholly within the city, the r for persons calls leaps to .93, and for property calls moves up to .68.

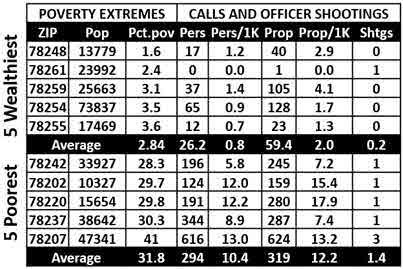

This table compares San Antonio’s five poorest and five wealthiest ZIP’s (78242, where Ms. Perez was killed, is the fifth poorest). It sets out percent of citizens who live in poverty, raw numbers and rates per 1,000 pop. for calls to police about crime against persons and property crimes during January 2023, and, using data from the Gun Violence Archive (GVA), the number of citizens struck by police gunfire and wounded or killed between January 2021 and July 2023.

Contrasts between poor and wealthy ZIP’s are pronounced. For example, check out that thirteen-fold difference between person call rates and the six-fold difference between property call rates.

Ms. Perez’s killing took place in the highly impacted 78242, where more than one in four persons (28.3 percent) reside in poverty. Could that have influenced the officers’ response? Cops are human. Their work product can be distorted by personal quirks, the foibles of coworkers and superiors, and, particularly, by the circumstances they encounter on the streets. As our essays have repeatedly pointed out, neighborhoods that are burdened by violence and gunplay can breed officer attitudes and behaviors that cops assigned to more privileged venues might find disgusting. (For a classic work about such things check out James Q. Wilson’s “Varieties of Police Behavior,” with which your author regularly burdened his students.)

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

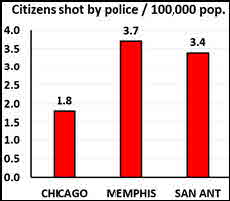

Our first two tables set out violent crime rates for San Antonio and four other cities during the first six months of 2021 and 2022. Chicago and Memphis seemed particularly stricken. Yet according to GVA data, San Antonio PD’s rate of shooting citizens was nearly twice Chicago’s and nearly matched Memphis, whose violent crime rates are almost twice as high. And grab another look at the “shtgs” column in the above table. San Antonio police shootings seemed substantially more likely in the poorest areas. Bottom line: concerns that some San Antonio officers might have let the workplace distort lethal-force decisions can’t be simply brushed aside. Our first two tables set out violent crime rates for San Antonio and four other cities during the first six months of 2021 and 2022. Chicago and Memphis seemed particularly stricken. Yet according to GVA data, San Antonio PD’s rate of shooting citizens was nearly twice Chicago’s and nearly matched Memphis, whose violent crime rates are almost twice as high. And grab another look at the “shtgs” column in the above table. San Antonio police shootings seemed substantially more likely in the poorest areas. Bottom line: concerns that some San Antonio officers might have let the workplace distort lethal-force decisions can’t be simply brushed aside.

Does this let the three ex-cops “off the hook”? Certainly not. But to prevent endless replays, we must openly acknowledge that the disorder and lack of compliance common in poverty-stricken areas can poison officer decision-making and distort their response. However, the ultimate “fix” lies outside of policing. As we habitually preach in our Neighborhoods essays, a concerted effort to improve the socioeconomics of poor places is Job #1. Not-so-incidentally, that could also improve the dodgy behavior of some citizens. And good cops would find that most welcome!

UPDATES (scroll)

9/27/24 “If we don’t arrest you, we get days at home [without pay]. I can’t afford no days at home.” That’s what a Lexington, MS police officer told a motorist he was taking to jail for...driving without a license. Home to 1,200 residents, mostly Black and poor, the poverty-stricken city apparently needs all the income from fines that its police can bring in. That’s apparently led the “mostly” Black force to make “unnecessary arrests” and needlessly use force. And that just led DOJ to launch a formal investigation.

8/25/23 Are cops needlessly spurring conflict through their choice of words and delivery? An academic study will scour bodycam videos of 1,000 officer-citizen encounters during a three-year period to identify the characteristics of successful interactions. Artificial intelligence will be used to select episodes where officers “cross the line” and to recommend solutions. Variables will include officer age and experience, citizen race, and the location of a stop.

7/24/23 In “The Myth of the Superhuman Cop”, Force Science’s Von Kliem suggests that given the swiftly changing and uncertain circumstances that officers face, even the most competent and highly trained cops may be unable to speedily and accurately respond to rapidly-emerging threats, let alone attempt to de-escalate. Human capabilities are limited, and factors such as obstructions to vision, insufficient time to observe, and inability to coordinate with others may inevitably lead to poor endings.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Special topics: Craft of Policing Neighborhoods Police and the Mentally Ill

See No Evil - Hear No Evil Confirmation Bias can be Lethal Good News/Bad News

Third, Fourth and Fifth Chances Another Victim: The Craft of Policing Place Matters

When Must Cops Shoot? (I) (II) Informed and Lethal

De-escalation: Cure, Buzzword or a bit of Both? Working Scared

Posted 4/17/23

PILING ON

Swarming unruly citizens and pressing them

to the ground invites disaster

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. On March 31, 2020, two months before the murder of George Floyd forever tarnished American policing, a resident of Southern California lost his life in an appallingly similar way.

During the early morning hours of March 31, 2020 a pair of California Highway Patrol officers stopped Mr. Edward Bronstein, a thirty-eight year old Burbank man, on suspicion of drunk driving. He was detained and transported to a CHP station. On arrival, officers asked his consent for a blood draw. (That may have been due to previous DUI’s. See below.) But Mr. Bronstein refused, so they obtained a telephonic warrant and summoned a nurse.

Seven CHP officers were involved. Five were hands-on. A sixth stood to the side, and a Sergeant videoed the encounter. (Click here for our condensed, captioned and backlit version, and here for the full-length CHP video). Officers placed Mr. Bronstein on his knees and tried to get him to change his mind. But Mr. Bronstein wouldn’t, so they pressed him to the ground. Mr. Bronstein was instantly scared and “promised” he would comply. But an officer said “too late.”

Click here for the complete collection of compliance and force essays

These images depict what happened next. About 1:25 mis. into the CHP video, one officer is shown pressing down on Mr. Bronstein’s neck area with his knee (we outlined its approximate shape). Less than a minute later (2:09 on the video) Mr. Bronstein begins screaming “I can’t breathe.” An officer replies “then stop yelling.” The blood draw began about 2:50 mis. in. By 3:10 mis. Mr. Bronstein seemed unresponsive. But the procedure continued. At about 4:30 mis. the nurse checked for a pulse in various places, then tried to slap Mr. Bronstein awake. After nine minutes had passed the officers raised Mr. Bronstein’s torso, and the nurse used a stethoscope to check for a heartbeat. About 13:30 mis. someone utters “heart attack”. Active resuscitation measures don’t visibly begin until nearly fifteen minutes into the encounter. That’s about twelve minutes after Mr. Bronstein seemingly passed out.

“Violent and Vulnerable” discussed the syndrome of “excited delirium,” which the emergency medical community formerly applied to highly agitated persons, typically under the influence of drugs (see the American College of Emergency Physicians’ 2009 “White Paper on Excited Delirium Syndrome”). When physically restrained, some cease breathing altogether or go into cardiac arrest. But the EMS World white paper that we originally linked is no longer online. It’s been replaced by “A New Lens on Excited Delirium.” According to the site editor, concern had developed that “excited delirium” had become “a catchall diagnosis that obscures other causes of death” and allows police to excuse the physical abuse of minorities (i.e., the George Floyd episode).

Still, agitated persons continued to perish. A 2021 report by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), offers a new, improved syndrome: “hyperactive delirium”:

Hyperactive delirium with severe agitation, a presentation marked by disorientation and aggressive words and/or actions, is an acute life-threatening medical condition that demands emergency medical treatment…(pg. 2)

Fine. So was “hyperactive delirium” a factor in Mr. Bronstein’s death? ACEP’s website notes that (just like the bad, old “excited” delirium) forceful intervention can play a key role:

…Hyperactive delirium syndrome is a life-threatening constellation of symptoms manifested as a clinical syndrome. The combination of vital sign abnormalities, metabolic derangements, altered mental status/agitation, and potential physical trauma raises serious concerns for impending danger. Patients with this condition are at high risk of...secondary physical trauma that may result from physical restraint to allow for evaluation of the patient by emergency personnel.

What’s more, drugs make things worse. “Hyperactive delirium with severe agitation, as well as hyperadrenergic physiological states, commonly results from stimulant intoxication and may be caused solely by exposure to this class of drugs.” (pg. 7)

For Mr. Bronstein, it was apparently “all of the above.” According to the L.A. County Coroner, the cause of death was “acute methamphetamine intoxication during restraint by law enforcement.” A highly agitated man who was under the influence of a powerful, mood-altering drug had a gaggle of officers press on his chest. Given Mr. Bronstein’s fragile condition – call it “hyperactive delirium” if you wish – that application of force likely interfered with his breathing and brought on cardiac arrest.

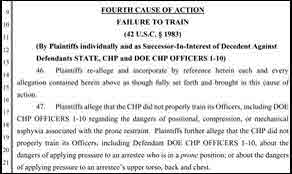

Leaving out any mention of “delirium”, excited or otherwise, this causal chain forms the basis of a Federal civil rights lawsuit filed by Mr. Bronstein’s family against the state, the CHP, and each of the officers (2:20-cv-11174-FMO-JEM). Here’s a brief extract from its “Fourth Cause of Action, Failure to Train” (pg. 10):

Plaintiffs allege that the CHP did not properly train its Officers, including DOE CHP OFFICERS 1-10 regarding the dangers of positional, compression, or mechanical asphyxia associated with the prone restraint. Plaintiffs further allege that the CHP did not properly train its Officers...about the dangers of applying pressure to an arrestee who is in a prone position; or about the dangers of applying pressure to an arrestee’s upper torso, back and chest. Plaintiffs allege that the CHP did not properly train its Officers, including DOE CHP OFFICERS 1-10 regarding the dangers of positional, compression, or mechanical asphyxia associated with the prone restraint. Plaintiffs further allege that the CHP did not properly train its Officers...about the dangers of applying pressure to an arrestee who is in a prone position; or about the dangers of applying pressure to an arrestee’s upper torso, back and chest.

A recent filing indicates that a settlement is in sight, and a hearing to approve it is scheduled for October.

Full stop. It’s not just civil litigation that the officers face. On March 28, 2023, just three days shy of the three-year mark, a new D.A., George Gascon, charged the R.N. and the seven CHP officers with violating Penal Code section 192(b), involuntary manslaughter, a felony, in this case “the commission of a lawful act which might produce death, in an unlawful manner, or without due caution and circumspection”. Each officer was also charged with section 149, a misdemeanor that applies whenever an officer “under color of authority, without lawful necessity, assaults or beats any person.” Here’s an extract from the D.A.’s online announcement: