|

Posted 9/4/18

THE BAIL CONUNDRUM

Bail obviously disadvantages the poor. What are the alternatives?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. On September 19, 2017 Mickey Rivera walked out of jail, a free man. Well, relatively free. Unable to post $35,000 bail, he had been locked up for more than two years awaiting trial for his role in the 2015 gang-related killing of a Boston man. In August 2017, though, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled in Brangan v. Commonwealth, an unrelated case, that absent specifically documented reasons, cash bail must not outstrip a defendant’s ability to pay. After all, bail isn’t intended as punishment but “to provide the necessary security for [a defendant’s] appearance at trial.” Given that decision, Rivera’s lawyers appealed. Despite his substantial criminal record, Rivera’s bail was reduced to $1,000. He paid up, was outfitted with a tracking device and let go. That, a legal expert told the Boston Globe, was perfectly appropriate:

Nancy Gertner, a retired federal judge and a senior lecturer at Harvard Law School, defended McGuire’s decision to reduce bail, saying he was following a state court decision that is part of a national bail reform effort to prevent people from being jailed before trial simply because they are poor. “What the judge did is exactly right,” Gertner said.

Real life tends to muddy things, and this case is no exception. In June 2018, nine months after being set loose, Rivera was arrested for drunk driving. Although he was still awaiting a criminal trial, Rivera was released without bail (his driver license was suspended.) One month later, on July 28, Massachusetts cops observed him speeding and driving erratically. Rivera took off, with cops in pursuit. The chase ended when Rivera slammed head-on into another vehicle, killing a man who had just visited his wife and newborn daughter in the hospital. Rivera was also killed, and a passenger in his vehicle died the following day.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

As one might expect, Rivera’s case led to considerable recrimination and finger-pointing. Lots of criticism was directed at the judges who reduced Rivera’s bail in the killing to a token amount and, much later, let him walk on the DUI. Both were blamed for not making the effort to articulate the need to set a substantial bail amount, even beyond Rivera’s ability to pay, as state law and the court decision allow. Of course, the judges had a built-in excuse: despite his many run-ins with the police, Rivera had always shown up.

Showing up? Is that what bail is all about? Apparently, the answer is yes. Bail’s only mention in the Constitution is in the Eight Amendment, which stipulates that “excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” While these few words don’t address bail’s purpose, Stack v. Boyle (342 U.S. 1, 1951), the leading Supreme Court case on point, prohibits setting bail “at a figure higher than an amount reasonably calculated to fulfill the purpose of assuring the presence of the defendant….” Here is how Justice Robert H. Jackson suggested that be determined:

Each accused is entitled to any benefits due to his good record, and misdeeds or a bad record should prejudice only those who are guilty of them. The question when application for bail is made relates to each one’s trustworthiness to appear for trial and what security will supply reasonable assurance of his appearance…This is not to say that every defendant is entitled to such bail as he can provide, but he is entitled to an opportunity to make it in a reasonable amount.

Wait a minute. Doesn’t a suspect’s dangerousness also matter? Unfortunately, the underlying offense in Doyle was nonviolent so that concern didn’t come up. For a clue we return to Brangan, the Massachusetts case. There the crime was armed robbery, so the justices had no option but to address dangerousness. And their answer, as far as bail is concerned, was “no”:

…a judge may not consider a defendant’s alleged dangerousness in setting the amount of bail, although a defendant’s dangerousness may be considered as a factor in setting other conditions of release. Using unattainable bail to detain a defendant because he is dangerous is improper….(emphasis ours)

That doesn’t mean that the nature of a crime is irrelevant. After all, serious crimes carry serious punishment, and that might make an accused more likely to flee. In fact, Brangan and its precedents require that factors such as the nature of an offense, community ties, mental condition, criminal record and failures to appear (FTA) be considered when setting bail, but only to evaluate the risk of flight. And there are limits. After all, bail inherently discriminates against the poor. Here’s another extract from Brangan:

A bail that is set without any regard to whether a defendant is a pauper or a plutocrat runs the risk of being excessive and unfair. A $250 cash bail will have little impact on the well-to-do, for whom it is less than the cost of a night's stay in a downtown Boston hotel, but it will probably result in detention for a homeless person whose entire earthly belongings can be carried in a cart.

That argument parallels the views of justice activists who have called for the elimination of bail altogether. Here, for example, is an extract from the ACLU “Smart Justice” website:

…bail was supposed to make sure people return to court to face charges against them. But instead, the money bail system has morphed into widespread wealth-based incarceration. Poorer Americans and people of color often can’t afford to come up with money for bail, leaving them stuck in jail awaiting trial, sometimes for months or years. Meanwhile, wealthy people accused of the same crime can buy their freedom and return home.

By design, offense severity and prior record strongly influence bail setting and pretrial detention. Research has also revealed that in comparison to white arrestees, blacks and Hispanics are less able to afford bail and less likely to be released without posting bail, thus more likely to remain in pretrial custody. For example, see “Sentenced to Pretrial Detention: A Study of Bail Decisions and Outcomes” (a review of recent New Jersey data) and “Recommended for release on recognizance: Factors affecting pretrial release recommendations” (an earlier review in Toledo.)

Concerns about extralegal disparities led New Jersey to implement a statewide “risk assessment” system in 2017. Pre-trial investigators collect information to help courts determine whether releasing defendants through “non-monetary means” would unduly risk their flight or imperil public safety. Cash bail remains an option but its use is heavily discouraged. As one might expect, the bail industry balked. So far, though, the statute has survived legal challenges.

Determined not to be left out, liberal-minded California recently enacted an even more sweeping measure that, as of October 2019, does away with bail altogether. Other than under exceptional circumstances, persons arrested for misdemeanors will be summarily released. Like in New Jersey, arrestees charged with more serious crimes would be evaluated by pretrial services, which could release those who pose a low-to-moderate risk to public safety or of nonappearance. Other defendants could thereafter be released by the courts, which could impose only non-monetary conditions. Characters who seem so likely to flee, or pose such an extreme threat to public safety that releasing them under any conditions seems unwise, would be subject to preventive detention. As one would expect, this involves substantial due-process safeguards, including a hearing. Other states (e.g., New Jersey, Massachusetts) have similar provisions.

One might think that minimizing the use of bail or, as in California, eliminating it altogether would satisfy activists. But according to a recent article in Politico one would be wrong: “Social justice advocates that had once championed the initiative to abolish cash bail mobilized against the final iteration of the [California] bill, which they saw as having morphed from righteous to dangerous.” What’s so “dangerous” about risk assessment and, as a last resort, preventive detention? Given the presumption of innocence, apparently everything: “In critics’ eyes, that means California will continue to give local judges the sweeping authority to keep people incarcerated before they’re convicted of anything.” Similar concerns have arisen in New Jersey and elsewhere.

Law enforcement officers must deal with the consequences of poor release decisions, so they usually favor a short leash. Four months after New Jersey’s provisions took effect, Jules Black, an ex-con, was arrested for having a gun. Assessed as low-risk, he was released without bail. Within hours Black allegedly cornered one of his enemies and shot him dead. According to a local jailer (he’s also president of the police union) career criminals are taking advantage of the reforms: “I’m seeing the same exact people every week. I’m just seeing them come in with new charges. It’s more work for officers. It’s a lot more work for them.” Concerns that the new procedures were proving too lax were seconded in an NorthJersey.com editorial:

In particular, officers say the new law’s risk assessment, or Public Safety Assessment, leaves too much to chance and is allowing, in some instances, violent-prone individuals to be back out on the street shortly after their court appearances. This, they say, is also bringing more pressure and stress to officers on patrol.

Is assessment a solution? Newfangled protocols supposedly let authorities assign applicants for release to the appropriate risk pool. To be sure, paying specialists to make distinctions will produce…distinctions. But whether these yield groups with markedly different, real-world propensities to engage in misconduct is something else altogether.

Neither is bail a guarantor of good outcomes. “Googling” instantly turned up a recent, troubling anecdote. On May 13, a Wisconsin man with an extensive criminal record that includes “bail jumping” was out on $7,500 cash bond for a string of crimes when an officer tried to pull him over for a traffic violation. After a pursuit (a cop wound up getting dragged a short distance by the suspect’s car) the man was arrested on multiple charges.

This time he was detained without bail, right? Wrong. Cash bond was set at $1,000.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Pre-trial release, on bail and otherwise, is ubiquitous and surprisingly permissive. A recent study of eleven major California counties tracked more than one and one-half million bookings (1,563,837) between October 2011 and October 2015. Forty-one percent of the arrestees were released before trial, split about 60/40 percent between misdemeanors and felonies. Of these, a bit more than a quarter (27.8 percent) had to post bail, most often for a felony offense. About seven percent of the bookings (112,445) were for FTA on a prior charge. Thirty-eight percent of these defendants (43,029) were again let go. A previous study, of persons released from Dallas County jail in 2008, suggested that failure to appear is frequent. Including misdemeanors and felonies, the rate ranged from 23 percent of those released on bail to 39 percent of those who were simply cleared by pretrial services (N=29,416). Another, “An Experiment in the Law: Studying a Technique to Reduce Failure to Appear in Court,” about individuals released on misdemeanor charges in Nebraska during 2009-10, yielded a control group FTA rate of 12.6 percent (N=7,865).

FTA isn’t the only issue. Released persons must often comply with other conditions; for example, wear an ankle monitor, keep away from certain persons and places, and so on. But public safety agencies have limited resources, and their practitioners can only do so much. Whether it’s old-fashioned cash bail or a newfangled assessment, the sheer magnitude of pre-trial release, the uncertainties of evaluating applicants, and the frailties of human nature inevitably create error, and along with it a substantial threat to the public and police. At a certain point – and from the flub-ups, we’ve probably reached it – trying to fine-tune outcomes becomes an exercise in wishful thinking. Release more, and there will be more news headlines and more cause for essays like this. That’s the one certainty we’ll never escape.

UPDATES (scroll)

8/16/24 Did reform-minded moves to do away with cash bail increase crime? A comparison of cities with and without bail reform during 2015-2021 did not reveal a criminogenic effect for either property or violent crimes. However, according to the study’s report (see Table 1), each city that reported having eased its release policies limited the benefits to persons charged with misdemeanors or, at most, non-violent crimes. Many releases were also contingent on passing a risk assessment. Report

6/10/24 In 2017 New Jersey implemented rules that eliminated pre-trial detention simply because a defendant could not afford cash bail. Instead, decisions to detain would be based on risk assessments. Through 2019, the final year assessed, detentions dropped “dramatically,” but there was no evidence of a corresponding increase in firearms deaths or gun violence. New Jersey’s bail reform policies presently remain in effect. However, the numbers held pre-trial have also increased.

9/5/23 In 2019 California allocated $75 million to fund projects in 16 trial courts throughout the state to help judges make pre-trial release decisions and improve outcomes. Key components included expanding the pre-release process, using a specialized assessment tool, and furnishing special services for releasees, including a court date reminder system and mental health, housing and other programs. A recent assessment reported that pretrial releases increased by 5.7% for misdemeanors and 8.8% for felonies, while rearrests fell 5.8% and 2.4%. Misdemeanor FTA’s fell 6.8 percent; felony FTA’s increased 2.5%.

5/18/23 Ruling that cash bail can violate equal protection guarantees, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge issued a preliminary injunction restoring the zero-dollar bail provisions for minor crimes that were in effect during the pandemic. His order does not apply to arrests based on warrants, nor to violent misdemeanors or violent or serious felonies. Injunction

1/2/23 Provisions in Illinois’ new “SAFE-T” Act that eliminate cash bail and institute other pre-trial changes have been placed on hold by the state's Supreme Court to “maintain consistent pretrial procedures throughout Illinois” while it considers an appeal by prosecutors who object to the easings. But a prosecutor who favors the Act said that bail discriminates against the poor. He pointed to a recent example of a potentially dangerous defendant who had the means to make bail and was thus set free.

12/30/22 Only days before Illinois’ “SAFE-T” Act was set to take effect, a state judge agreed with a lawsuit against the measure by a coalition of prosecutors that a key provision - the elimination of cash bail - ran afoul of an Illinois Supreme Court decision giving judges an “independent, inherent authority to deny or revoke bail”. Only problem is, Cook County (Chicago) wasn’t part of the prosecutors’ lawsuit, so whether “SAFE-T” will be fully operative in the state’s capital city is anyone’s guess.

12/21/22 To keep Illinois’ elimination of cash bail from taking effect on Jan. 1, a coalition of State prosecutors asked a judge to declare Gov. Pritzker’s cherished cause unconstitutional. Changes in the “SAFE-T” Act give judges some discretion in detaining dangerous persons, but these are in their view insufficient. According to the challenge, the Act touches on too many things and is thus fatally flawed.

12/7/22 Concerns by victim rights groups led Governor J.B. Pritzker to sign an amendment to Illinois’ SAFE-T Act, which eliminates cash bail as of January 1. Judges will have specific standards to determine whether defendants can be held, and additional crimes including aggravated robbery, second-degree murder and home invasion have been added to the list of serious offenses that can qualify accused thought by judges to be dangerous to be detained. However, many of the state’s chief prosecutors have sued to block the law, so its future remains unclear.

5/4/22 According to the progressively-minded L.A. Times, most of progressive L.A. District Attorney George Gascon’s prosecutors back the current campaign to recall him from office. He earned their disapproval from the very start, when he barred them from seeking the death penalty or asking for sentence enhancements. And while Gascon has moderated some of his stances - prosecutors can again (with approval) ask judges to impose life terms for murder - one-hundred twenty have resigned, leaving their colleagues with insufferable caseloads.

3/23/22 An op-ed by three Illinois head prosecutors urgently calls on legislators to substantially modify the “SAFE-T Act.” Passed as a 2021 reform, it set a January 1, 2023 deadline for eliminating cash bail (persons awaiting trial could still be electronically monitored) and eliminates repeat offender, “three-strikes” and “felony murder” sentencing enhancements. According to the writers, these and other relaxations ignores the rights of victims and flies in the face of a sharp increase in violent crime. (See 12/7/22 update)

2/17/22 After facing threats of recall over his progressive policies, George Gascon, L.A.’s liberally-minded D.A. tweaked his much-criticized decision to forbid prosecutors from trying juveniles as adults. Instead, he now requires that such moves be approved by a supervisor. That change, he says, is in response to a looming judicial decision on Proposition 57, whose provisions could be interpreted to force the mass release of juveniles who were convicted as adults, and even for the most serious crimes. Gascon subsequently announced he would again allow prosecutors, with his approval, to seek life sentences, whose imposition he forbid when taking office.

1/13/22 As violence soars, even some “Blue” legislators are “reexamining” a provision of Illinois’ massive 2021 criminal justice reform bill that eliminates cash bail as of January 1, 2023 to insure that persons charged with attempted murder and other violent crimes aren’t simply let go. (Click here for the bill text and here for a summary.) After all, a Democratic legislator’s husband recently traded gunfire with suspects who carjacked the pair in a Chicago suburb. Under pressure from the “Reds,” legislators have also been tweaking other parts of the law, including provisions on officer decertification.

9/8/21 Stung by California voter’s rejection of an initiative to eliminate cash bail, reformers now seek to drastically limit its cost. A new proposal caps the final charge for those who comply with court orders at five percent of the ten-percent fee. For example, one’s out-of-pocket cost for a bail of $50,000 is $5,000. Should they fully comply, they’d get all but $250 back. That, according to bail firms, would effectively put them out of business. But a bill to that effect is winding its way through the Legislature.

9/1/21 In September 2018 a 29-year old Chicago man, Rayon Allen, struck and killed an elderly pedestrian while recklessly passing another car. He tried to pry the body loose from his tires, then sought to steal a car. Allen eventually pled guilty to reckless homicide and got 30 months probation and drug counseling. On August 29, while still on probation, he ran over two pedestrians and a bicyclist, injuring two critically. Allen was arrested for DUI and leaving the scene. And he was released again.

5/23/21 Cook County (Chicago) has 1,544 persons awaiting trial for serious felonies at home. They’re wearing ankle bracelets. Ninety four face murder charges; 33, carjacking; 569, “aggravated unlawful use of a weapon.” And so forth. These numbers are vastly larger than pre-pandemic. According to Chief Judge Timothy Evans, who advocates criminal justice reforms, COVID forced an emptying of the jails. In any event, those released are not a threat and must be presumed innocent until proven otherwise.

3/26/21 In a potentially far-reaching decision, the California Supreme Court ruled that defendants must not be denied release simply because they cannot afford bail, and that if an amount within their means cannot be set measures that are “less restrictive” than confinement (such as wearing an ankle monitor) must be considered. (In re Kenneth Humphrey, no. S247278)

2/23/21 Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed a bill that eliminates cash bail in 2023. Civil libertarians enthusiastically backed the measure, which was reportedly inspired by the death of George Floyd. Some worry, though, that judges might overuse the right to detain offenders they consider dangerous. The Chicago Tribune announced its opposition because it fears that dangerous persons will be released into the community. Police and prosecutors have consistently opposed the bill as it mandates release of pre-trial arrestees for a broad range of crimes, “irrespective of their likelihood of re-offending, the danger they pose generally to the public, or their willingness to comply with conditions of their release.”

2/9/21 A judge ruled that plans by George Gascon, Los Angeles County’s new, progressive D.A., to end the use of sentencing enhancements for categories such as felons, gang members and use of a weapon violates state law. With violence in L.A. way up, that promise drew flack from victims, judges and his own staff. Gascon has directed that his prosecutors ask judges to release arrestees without bail except for violent felonies, and has prohibited seeking the death penalty, trying juveniles as adults, and prosecuting first-time violators for minor, “nuisance” crimes such as trespass and loitering, He has also promised more emphasis on prosecuting officers who use excessive force.

11/22/20 In Sept. 2017 Chicago courts facilitated pre-trial release by eliminating or reducing bail. In six months 500 additional defendants were released (9,200 instead of 8,700). A study revealed that those released after the change were slightly more likely to FTA but equally likely to reoffend (17 percent) as those released under the old guidelines. Overall Chicago crime rates did not change.

11/5/20 Progressive fears that eliminating cash bail “would automate racial profiling, give unchecked power to judges and increase funding and power for corrupt probation departments” led voters to reject California Proposition 25, which would have based release decisions on judicial evaluations of public safety and flight risk.

11/3/20 Early releases have plagued Europe’s fight against extremism. Yesterday evening a terrorist armed with an assault rifle unleashed a fusillade of gunfire in Vienna, Austria, killing four and injuring fourteen, six critically. Kujtim Fejzulai, 20, had been sentenced to 22 months last year for trying to join the Islamic state but was granted an early release. In London, a terrorist who was granted early release in 2018 after his conviction in a bomb plot went on a stabbing rampage in London the very next year, killing two before police shot him dead.

11/2/20 Last November Chicago authorities charged Juan Torkelson with first-degree murder and attempted murder for stabbing one person dead and wounding two others. He was on the loose until May when a police fugitive team found him. But he was released on $10,000 bond and placed on home detention because of the coronavirus. On October 28 Torkelson pulled a gun on Ohio deputies who stopped him for traffic violations. They took cover and he fled. His whereabouts are unknown.

4/23/20 Released without bail because of the pandemic, some California jail inmates who were being held pending trial have been quickly rearrested on new crimes. Rocky Lee Music, 32, an ex-con, allegedly committed a carjacking twenty minutes after his release from a jail where he was being held for car theft. Owen Aguilar, 27, who was being held for criminal threats, was arrested on multiple counts of arson a few days after his release. Kristopher Sylvester, 34, was let go twice. Two weeks after his release from jail, where he was being held on multiple counts of burglary, he and three buds were arrested for a string of car thefts. All four had substantial records, and all were let go.

3/11/20 A new academic study contradicts earlier findings by Chicago’s court system that bail reforms which increased the number of persons released before trial did not lead to more crime. Researchers instead found that after the 2017 loosening, the proportion of releasees charged with new crimes increased by 45 percent, and with new violent crimes by 33 percent. They also confirmed the Tribune findings reported below (see 2/13/20 update).

2/13/20 An extensive Chicago Tribune analysis of the effects of bail reforms implemented by the county’s chief judge, including the reduction and elimination of cash bail, concludes that claims it reduced violent crime are based on flawed data and a purposely narrow definition of a crime of violence. Twelve homicides were allegedly committed in Chicago during the first nine months of 2019 by persons released under the new rules.

1/1/20 New York police and prosecutors warn that new state law which, regardless of an accused’s criminal record, bans cash bail outright for most misdemeanors and “non-violent” felonies, will lead to more crime and witness intimidation. While civil libertarians counter that such fears are overbown, the changes may keep some accused stalkers, robbers and burglars from being detained.

4/1/19 With its new budget, New York State eliminated cash bail “for most misdemeanor and non-violent felony offenses.” It also required that instead of making a custodial arrest police issue “appearance tickets” for most misdemeanors and “Class E” felonies.

2/1/19 New York City offers a no-bail “supervised release” pre-trial program for nonviolent offenders that does not require wearing monitors. Releasees regularly meet with case managers and are offered community services and drug treatment. So far twenty percent have reoffended while on the program, 12 percent for misdemeanors and eight percent for felonies.

11/23/18 Despite official concerns, a human rights group used donated funds to bail out “64 adult women and 41 high-school aged males” mostly facing unspecified felony charges in New York City. All received re-entry assistance including a place to live, a cellphone and free public transportation for two months. Nearly all reportedly complied with reappearance and kept out of trouble.

11/2/18 According to the Pretrial Justice Institute, an anti-bail group, cash bail not only discriminates against minorities and the poor but actually makes crime worse. Instead, PJI advocates the use of pretrial assessments and provision of necessary “support, services, and supervision.”

9/23/18 As human rights groups prepare to bail out 500 pre-trial detainees from New York City’s Rikers Island jail, prosecutors and police fret about the consequences for witnesses and victims. Mayor de Blasio only wants those accused of low-level crimes to be freed, but advocates ridicule fears that “streets will run with blood” and insist that everyone eligible for bail will be considered.

9/9/18 California bail agents are scrambling to place a voter referendum on ballot in 2020 to nullify the new state law that does away with cash bail as of October 2019. Along with civil libertarians who oppose granting judges broad release discretion, they also plan to tie up the new law in litigation.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Bail and Sentence Reform special topic

Must the Door Revolve? Risky Business

Posted 5/21/18

THE BLAME GAME

Inmates are “realigned” from state to county supervision. Then a cop gets killed.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Cops would worry less if their workplace was more forgiving. But it’s not. Legal rules and enforcement practices often seem out of sync with the “real world.” There are never enough resources to consistently do a good job. Accurate information is frequently lacking, and there is often little chance to seek it out. Citizens and suspects are unpredictable and dangerous. That’s why cops want evildoers behind bars. Big bars. Throw away the key: problem solved.

What officers want isn’t necessarily what they get. California’s cops got their first taste of the “new normal” in 2011. Two years after Federal judges imposed a cap on the state’s overflowing prisons, legislators passed AB 109, the “Public Safety Realignment Act,” shifting confinement and post-release supervision of “non-serious, non-violent [and] non-sex” offenders from state prisons to county jails and probation departments. Three years later Proposition 47 reduced many felony drug crimes and all theft and stolen property cases with losses under $950 to misdemeanors. And two years after that, Proposition 57, the “Public Safety and Rehabilitation Act of 2016,” made it easier for inmates to earn release credits and for “nonviolent” offenders sentenced on multiple charges to win early parole.

Prosecutors and police opposed “realigning” prisoner populations and facilitating early release. They lost. After all, weren’t crime rates way down from their peaks? With reformers howling and politicians reluctant to pay for more prisons, all three measures remain on the books.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

No, the sky hasn’t fallen. But change always carries consequences. During the first year of realignment, as the state prison population dropped by twenty-six thousand, jail populations surged by over 8,500. County lockups were quickly swamped, forcing authorities to release arrestees whom police wanted to keep in custody. Sentences were waived or cut short, and parolees whose supervision was shifted to the counties remained on the streets despite repeated violations. One, Sidney DeAvila, a sex offender, used his freedom to rape and murder his grandmother and cut her into pieces. A Democratic legislator bemoaned things. “It’s justice by Nerf ball. We designed a system that doesn’t work.”

The above graph is from FBI data. While the nation’s violent crime rate remained fairly steady between 2011-2016 (it fell two-tenths of one percent, from 387.1 to 386.3), California’s violent crime rate climbed 7.7 percent, from 411.1 to 445.3

In late 2016, with violent crime in California up for a third consecutive year, a columnist for the Sacramento Bee, the newspaper serving the state capital, wondered “whether releasing tens of thousands of criminals who otherwise would have been behind bars is having a negative effect.” His concern paralleled those of the public safety community, which was convinced that re-alignment was at fault for the increase.

Not everyone was so pessimistic. A September 2016 report by the Center on Criminal and Juvenile Justice (its mission is “to reduce society’s reliance on incarceration as a solution to social problems”) examined whether realignment contributed to the uptick in crime during 2014-15. Conceding that there was a lot of variation in the data, and that some counties did go the other way, investigators concluded that reducing the number of persons in jail did not cause the overall increase in crime.

In the same month, the influential Public Policy Institute of California used two-year old (2014) crime data to conclude that realignment was a success. (However, it did note that preliminary 2015 statistics were somewhat troubling.) One year later the institute conceded that realignment “had modest [adverse] effects on recidivism”; particularly, that parolees whose sentences were cut short and had their supervision turned over to county probation officers were more likely to reoffend.

That’s what happened with Michael Mejia. After serving a three-year prison term for a 2010 robbery, the heavily tattooed Los Angeles gang member stole a car and got two years for auto theft. Thanks to AB 109, he was released early, in April 2016, into the supervision of a local P.O. Mejia promptly amassed a string of violations and served brief stretches in jail. On February 20, 2017, nine days after his last release, he went off the deep end. Mejia murdered a cousin, stole a car, and when confronted chose to shoot it out, killing Whittier, Calif. officer Keith Boyer and seriously wounding his partner.

Mejia’s foul deed energized anti-realignment forces. A coalition of police organizations, prosecutors and victims’ rights groups is presently seeking to place the “Reducing Crime and Keeping California Safe Act of 2018,” an initiative that substantially rolls back the provisions of AB 109 and Propositions 47 and 57, on the November ballot.

Meanwhile, pro-realignment forces have pulled out all the stops. The Marshall Project, a “nonpartisan, nonprofit news organization that seeks to create and sustain a sense of national urgency about the U.S. criminal justice system” and the Los Angeles Times recently released an analysis that blames officer Boyer’s death on judges and probation staff who mistakenly let Mejia into the program, then gave him too many breaks. (Click here and here.)

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

We won’t parse the arguments pro and con in detail. What strikes us, though, is just how much is expected from those who must implement realignment’s provisions in the “real world.” The Marshall Project and Times insist (of course, with the benefit of hindsight) that Mejia’s poor conduct while under supervision required that his probation be revoked. But had they reviewed the innumerable examples of probation supervision that don’t end with the killing of a police officer, they would have discovered that Mejia’s behavior, which lacked “red flags” such as weapons or violence, was really quite ordinary.

In brief, he was your typical no-goodnik – until he wasn’t.

That’s not to say that Mejia should have been on the street. Still, if all who behaved similarly were reincarcerated, the correctional system would collapse. With confinement out of favor, prisons at capacity and local resources hard-pressed, thanks in part to realignment, prosecutors, P.O.’s and judges are under immense pressure to keep no-goodniks on the street. While that’s not what cops would prefer, they’re not calling the shots. At least, not until November.

UPDATES (scroll)

9/6/21 Families of victims murdered by juveniles have reacted bitterly to a decision by George Gascon, L.A.’s progressive new D.A., to forbid prosecutors from seeking judicial approval to keep juveniles convicted as adults in prison past their 25th. birthday. In 2016 Proposition 57 required that judges approve trying juveniles as adults. Those who were tried as adults solely under a prosecutor’s discretion would be reclassified as juveniles unless prosecutors sought and prevailed at a “transfer hearing.”

2/9/21 A judge ruled that plans by George Gascon, Los Angeles County’s new, progressive D.A., to end the use of sentencing enhancements for categories such as felons, gang members and use of a weapon violates state law. With violence in L.A. way up, that promise drew flack from victims, judges and his own staff. Gascon has directed that his prosecutors ask judges to release arrestees without bail except for violent felonies, and has prohibited seeking the death penalty, trying juveniles as adults, and prosecuting first-time violators for minor, “nuisance” crimes such as trespass and loitering, He has also promised more emphasis on prosecuting officers who use excessive force.

10/19/18 An appeals court expanded California’s Proposition 57 to cover formerly excluded “third strikers” who received life sentences. Up to 4,000 will now become eligible for parole.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Bail and Sentence Reform special topic

Cause and Effect Letting Go Must the Door Revolve? Police Slowdowns (I) (II)

Why do Cops Succeed? Is Crime Up or Down? More Criminals (on the street), Less Crime?

Rewarding the Naughty Ignoring the Obvious Reform and Blowback

Posted 1/25/18

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU BRAG ABOUT (PART II)

Citywide crime statistics are ripe for misuse

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Part I ended on a perhaps surprising note. Poverty and crime may be deeply interconnected, but our analysis of New York City crime data revealed that neither the city’s 2016 total major crime rate nor its change since 2000 were significantly related to the proportion of residents living in poverty.

NYPD tracks seven categories of major crime: murder, rape, robbery, felony assault, grand larceny, and grand larceny of motor vehicle. Their sum yields an eight measure, “total major crime.” (See table in Part I, below. NYPD reports yearly frequencies and percentage changes. Instead of raw numbers we used population data to generate rates per 100,000 residents.)

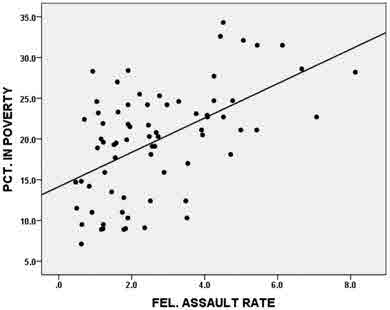

When total major crime didn’t yield the anticipated results we turned to one of its components, felony assault. Its 2016 rate per 100,000 pop. ranged from 0.5 (112th. and 123rd. precincts) to 8.1 (40th. pct.) (Precincts 14, 22 and 41 were excluded from analysis. See Part I). As expected, the mean rates of the ten lowest-felony assault rate districts (0.7) and the ten highest-rate districts (5.8) were significantly different (t=-4.9, p <.001). They also differed markedly as to poverty. That difference was in the expected direction: persons living in poverty comprise 15.8 percent of the population in low felony assault districts and 26 percent in the high rate districts (t=-3.7, p <.002, statistically significant).

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Correlation analysis was used to test the aggregate relationship between felony assault and poverty for all 73 precincts in this study. That revealed a statistically significant relationship in the “positive” direction, meaning that poverty and felony assault increased and decreased in unison (r=.54, p <.000). Here’s the graph (each precinct is a dot):

|

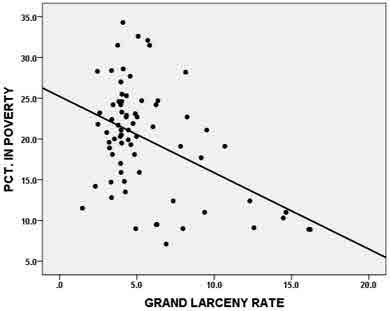

Statistically significant findings were also produced when we tested the relationships between poverty and the remaining violent crimes: robbery (r=.53, p <.000), rape (r=.46, p <.000) and murder (r=.48, p <.000). Poverty and all forms of violent crime went up and down together. There was also a significant positive relationship, of slightly lesser magnitude, between poverty and grand larceny of a motor vehicle (r=.31, p <.007; see comment below). In contrast, ordinary grand larceny (not of a vehicle) had a “negative” relationship with poverty: as one increased, the other decreased (r=-.43, p <.000, statistically significant). Here’s that graph:

|

We concluded that this was the reason why there was no observable relationship between total major crime and poverty. In New York, larceny of the “grand” kind requires a loss exceeding $1,000. These are presumably more common in affluent areas. As by far the most common form of serious crime, grand larceny’s strong negative relationship with poverty apparently countered the influence of the other factors. (Incidentally, the positive relationship between grand theft of a motor vehicle and poverty is likely caused by the fact that in New York, the theft of any vehicle valued at $100 or more – that’s two zeroes – is “grand.”)

Clearly, aggregate measures such as total major crime should be used with great caution. Fine. So, just how were the benefits of New York City’s crime drop distributed? Let’s compare crime rates for the ten poorest and ten most well-off precincts at two points in time: 2000 and 2016. (Precincts #14 and #22 were excluded for methodological reasons, and #41 for trustworthiness. See Part I.) We’ll begin with felony assault:

These graphs dramatically depict income’s differential effects. In 2016 the mean felony assault rate in the high-poverty precincts was nearly three times that of their well-off counterparts (474.5 v. 162.4, t=4.3, p <.001, a statistically significant difference.) Note that in both sets of precincts, scores clustered in observable groups. Felony assault rates in all but one of the low-poverty precincts topped out at 235.5. Add nearly two-hundred points to that and you’ll reach the lowest score (425.7) in a group of eight high-poverty precincts.

Poverty-stricken precincts had more lousy news. Excluding the besieged 40th., where the felony assault rate increased 15.8 percent between 2000-2016, its group’s mean decrease of 19.2 percent was less than half the 41.4 percent decrease enjoyed by the low-poverty group. That old saw about “the rich getting richer” seems to apply to felony assaults in the Big Apple.

Let’s look at the graphs for robbery:

In 2016 the mean robbery rate of the high-poverty precincts was slightly more than twice that of their low-poverty counterparts (333.4 v. 154.1, t=3.5, p <.003, difference statistically significant.) Except for the 18th. (rate=301.5) low-poverty precincts clustered at the lower end of the scale, topping out with the 9th.’s 198.8. One-hundred points later we encounter the trailing edge of a loose group of eight high-poverty precincts, with rates ranging from the 52nd.’s 325.9 to the 4oth.’s skyscraper-worthy 580.3.

Between 2000-2016 robbery rates declined 66.9 percent overall in low-poverty precincts and 44.5 percent in the high-poverty group. While both trends seem substantial, so was their difference (t=-4.2, p <.001, statistically significant). Rates were also distinctly dispersed: narrowly within low poverty (range 53.8 to 77.6 percent) and broadly within high poverty (19.9 to 66.8 percent.) Why this difference between differences we don’t know, but such volatility inevitably reminds us of tendencies at NYPD and elsewhere to fudge the numbers (see Part I).

And then we arrive at murder. This time we’ll begin with the high-poverty precincts:

Let’s skip rates and talk actual counts. In 2016 the range for the high-poverty group was from one murder in the 66th. to twenty-three in the 75th. These two precincts also had the extreme scores in 2000, when there were three killings in the 66th. and forty in the 75th. By 2016 murder receded in all high-poverty precincts but two, the 40th. and 73rd. In both killings ticked up a bit, going from thirteen to fourteen. Murders otherwise fell, most markedly in the 44th. (25-13), the 46th. (23-14), and especially, the 52nd., which plunged from twenty-five in 2000 to only three in 2016. (However, this precinct had twelve murders each in 2013 and 2015, so its numbers are volatile.)

We won’t sweat the details: for lots (but not all) poor New Yorkers, the murder news seems at least somewhat favorable. Now consider the horrors the wealthier set faced:

Six of the ten low-poverty precincts had zero murders (thus, zero rates) in 2016. Scores for the other four ranged from one killing in the 24th. to five in the 9th. Only two precincts, the 6th. and 78th., scored zero murders in 2000. Others ranged from one killing in the 18th. to four in the 76th. (note that a relatively low population of 43,643 lends its rate an inflated appearance.) Murders during the 2000-2016 period increased in only one low poverty precinct, the 9th., which went from three to four.

Glancing at the charts, does it seem that the rich get to ride up front, crime-wise, while the poor are consigned to the caboose? If so, that’s hardly unique to Gotham. Consider Los Angeles. In “Location, Location, Location” we mused about our hometown. Between 2002-2015 murders fell from 656 (rate=17.3 per 100,000) to 279 (rate=7.3), a stunning drop of fifty-seven percent. Now consider two of the dozens of communities that comprise the “City of Angels”: poverty-stricken Florence, pop. 49001, and upscale Westwood, pop. 51485. During 2002-2015 murder in Florence dropped from an appalling twenty-five killings (rate=51.0/100,000) to a merely deplorable eighteen (rate=36.7). Kind of like…New York City’s 44th.! Meanwhile murder in Westwood went up: from zero in 2002 to (yawn) one in 2015, a rate of 1.9. And that resembles…NYC’s 24th!

Back to New York. Our chart in Part I indicates that between 2000-2016 murders in Gotham fell from 673 (rate 8.4/100,000 pop.) to 335 (rate 3.9.) But let’s look within. In both the downtrodden 40th. (2016 pop. 79,762, poverty 28.2 percent) and the equally challenged 73rd. (pop. 86,468, poverty 28.6 pct.) killings ticked up from twelve to thirteen, yielding rates of 15.3 and 16.2, four times the citywide rate. Meanwhile, in the affluent 18th. (pop. 54,066, poverty 10.3 pct.), murders declined from one to zero (rate of zero) while in the large and fabulously rich 19th. (pop. 208,259, poverty 7.1 pct.) they fell from three to two, generating a rate of, um, one.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

That’s our “point.” New Yorks’ citywide poverty rate is 19.9 percent. As long as it has a sufficient proportion of well-off residents, it can use summary statistics to brag about “great crime drops” until the cows come home. Except that unlike citywide numbers, people aren’t composites. Can we assume that residents of the 40th. and 73rd. precincts feel – or truly are – as well served as those who live in the more fortunate 18th. and 19th.? What do poorer citizens think when they hear Mayor de Blasio boast that his administration has turned crime around? Are they as reassured about things as their wealthier cousins?

As we suggested in “Location,” it really is about neighborhoods. Aggregating seventy-six precincts because they’re located within a single political boundary, then acting as though the total truly reflects the sum of its parts, is intrinsically deceptive. Actually, when it comes to measuring crime and figuring out what to do about it, the 40th., the 73rd. and a host of other New York City precincts really aren’t in the Big Apple. They’re a part of that other America – you know, the one where the inhabitants of L.A.’s beleaguered Florence district also reside.

UPDATES (scroll)

7/25/20 It was the evening of July 3rd. 2020. In L.A.’s Florence neighborhood a Black youth left for the store. Neighbors later knocked on his parents’ door. They saw his sneakers on the body of a boy who was shot dead nearby. Otis Williams was fourteen. He was tall, well-mannered and didn’t like school.

6/24/20 New York City is experiencing a “surge” in shootings, with “more than double” during a recent three-week period compared with 2019. According to the NYPD data portal, murders are up by twenty-five percent, with 159 this year thru 6/14/20 (last year there were 127 during this period.) Shootings are also reportedly up elsewhere, including Chicago and Minneapolis.

1/7/20 New York City murder climbed from 293 in 2018 to 315 in 2019, a 7.5% increase. Robberies and felony assaults were also up, by 3.0 percent and 1.4 percent respectively. But property crime fell. According to Mayor Bill de Blasio, the long-term downward trajectory in NYC crime is “irreversible.” Meanwhile a 13-year old charged in the December 11 stabbing death of a New York City college student remains in custody while police build cases against his 13 and 14-year old companions.

12/4/19 During the last four decades wage growth in major cities, including New York and Los Angeles, has stagnated for the lower classes while, thanks to the new technologies, zoomed upwards for the better-off. That, according to New York’s Federal Reserve Bank, has made New York City one of the “top 10 most unequal metropolitan areas in the country.”

10/13/19 A shooting at an unsanctioned “social club” in Brooklyn’s economically-challenged Crown Heights neighborhood (poverty level 24.3 pct.) left four dead and three wounded. A July shooting in Brooklyn killed one and wounded eleven. Patrolled by NYPD’s 77th. Precinct, Crown Heights has experienced an increase in murder, from one to date in 2018 to nine so far this year.

10/4/18 Murders in most of New York City are down, but in a few neighborhoods they’re up. Gun killings in Brooklyn’s poverty-stricken Brownsville area went from seven to date in 2017 (36 wounded) to thirteen this year (47 wounded). A sixteen-year old black youth was the most recent victim. His alleged killer, also black, is only fourteen.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

See No Evil - Hear No Evil Worlds Apart...Not! What’s Up? Violence. Where? Where Else?

The Usual Victims Turning Cops Into Liars Place Matters Human Renewal

Repeat After Us: “City” is Meaningless Two Sides of the Same Coin Mission Impossible

Cops Aren’t Free Agents Police Slowdowns (I) (II) Why do Cops Lie? Be Careful (I)

Location, Location, Location Role Reversal Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy Cooking the Books

Liars Figure Too Much of a Good Thing?

Posted 1/15/18

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU BRAG ABOUT (PART I)

Is the Big Apple’s extended crime drop all it seems to be?

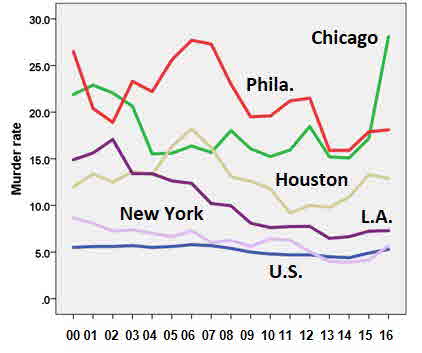

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Remember the “Great Crime Drop” of the nineties? Observers trace its origin to the end of a decade-long crack epidemic that burdened America’s poverty-stricken inner cities with unprecedented levels of violence. Once the crack wars subsided the gunplay and body count eased. But the news didn’t remain positive everywhere. In “Location, Location, Location” we identified a number of less-prosperous burgs (e.g., Chicago, St. Louis, Baltimore, Detroit, Newark, Cleveland and Oakland) that have experienced recent increases in violence. Murder in Chicago, for example, soared from 422 to 771 between 2013-2016 (it backed off a bit last year, but only to 650.)

In some lucky places, though, the crime drop continued. Few have crowed about it as much as New York City, which happily reports that its streets keep getting safer even as lawsuits and Federal intervention have forced cops to curtail the use of aggressive crime-fighting strategies such as stop-and-frisk.

Click here for the complete collection of crime & punishment essays

Indeed, New York City’s numbers look very good. As the above graph shows, its 2016 murder rate of 5.7 per 100,000 pop. was the lowest of America’s five largest cities and just a tick above the U.S. composite rate of 5.3. (Los Angeles was in second place at 7.3. Then came Houston, at 12.9 and Philadelphia, at 18.1. Chicago, with a deplorable 765 murders, brought up the end at 28.1.) Even better, it’s not only killings that are down in the Big Apple: every major crime category has been on a downtrend, reaching levels substantially lower – some far lower – than at the turn of the century:

What’s responsible for the persistent progress? New York City’s freshly-reelected Mayor and his police commissioner credit innovative law enforcement strategies and improved community relations. But in a recent interview, Franklin Zimring, whose 2011 book “The City That Became Safe” praised NYPD for reducing crime, called the reasons for its continued decline “utterly mysterious.”

Causes aside, when it comes to measuring crime, complications abound. Even “winners” may not be all that they seem. As we discussed in “Cooking the Books” and “Liars Figure,” lots of agencies – yes, including NYPD – managed to look good, or better than they should, by creating crime drops with tricks such as downgrading aggravated assaults (which appear in yearly FBI statistics) to simple assaults (which don’t). That problem has apparently not gone away.

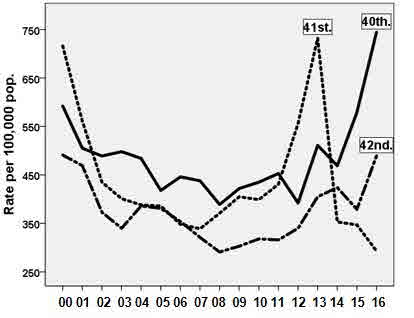

|

This graph uses the NYPD’s own data to display 2000-2016 felony assault trends in three highly crime-impacted precincts, the 40th., 41st. and 42nd., all in the Bronx. Just look at that pronounced “U” curve. Soon after cops outed NYPD for fudging stat’s (that happened in 2010) each precinct’s trends reversed. But the 41st.’s return to presumably more accurate reporting was only brief. Between 2013 and 2014 felony assaults in “Fort Apache” plunged from 732 to 353, an inexplicable one-year drop of fifty-two percent. And the good news kept coming, with 347 felony assaults in 2015, 293 in 2016 and a measly 265 in 2017.

There is plenty of reason to be wary of NYPD’s numbers. Still, assuming that the 41st.’s recent shenanigans are unusual – we couldn’t find another example nearly as extreme – the city’s post-2000 gains against crime seem compelling. But assuming that they’re (mostly) true, how have they been distributed? Has every citizen of the Big Apple been a winner? Let the quest begin!

NYPD has seventy-six precincts. Our main data source was NYPD’s 2000-2016 online crime report. (We excluded precincts #14, Times Square and #22, Central Park, for methodological reasons, and #41 because its recent numbers seem untrustworthy.) We also coded each precinct for its official poverty rate by overlaying the city’s 2011-2015 poverty map on NYPD’s precinct map. (For how NYC measures poverty click here.)

We’ll start with the total major crime category, which combines the seven major offenses. Its 2016 rate per 100,000 pop. ranged from 3.1 (123rd. pct.) to 45.6 (18th. pct., Broadway/show district.) Comparing the means for total major crime of the ten lowest-rate districts (6.25) with the means of the ten highest-rate districts (24.13) yields a statistically significant difference (t=-7.36, sig .000). So these groups’ total major crime levels are different. But their proportion of residents living in poverty is not substantially dissimilar. Actually, the raw results were opposite to what one might expect: the mean poverty rate was higher in the low major crime than the high major crime precincts (19.3 & 15.9, difference statistically non-significant.)

Similar results were obtained when comparing the 2000-2016 change in the major crime rate of the ten most improved precincts (mean reduction, 62.05%) with the ten least improved precincts (mean reduction, 14.69%). While the magnitude of these groups’ crime decline was significantly different (t=14.37, sig .000), the difference between the proportion of their residents who lived in poverty was slight and statistically non-significant (poverty mean for most improved, 19.28 pct.; for least improved, 21.31 pct.)

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

We then (by this point, somewhat unsteadily) ran the numbers the other way, comparing total major crime and its improvement over time between the ten high and ten low poverty precincts. Our central finding didn’t change: poverty wasn’t a significant factor. With all seventy-three precincts in the mix we also tested for relationships between total major crime rate and poverty, and between 2000-2016 changes in the major crime rate and poverty, using the r coefficient. Again, neither total major crime nor its change over time seemed significantly related to poverty.

So poverty doesn’t matter? New Yorkers are equally likely to benefit from the crime drop – or not – regardless of their place on the pecking order? As it turns out, not exactly. But that’s enough for now. We’ll deliver “the rest of the story” in Part II!

UPDATES (scroll)

4/30/22 Federal law prescribes the same penalty for possessing eighteen grams of cocaine powder as for one gram of smokable “rock.” Caused by the latter’s role in the inner-city violence of the nineties, the disparity falls hardest on Black persons. The “Equal Act of 2021,” which has passed the House, would equalize things. Thousands of Federal inmates could gain early release. But America’s polarization and its present struggle with violence make the bill’s future uncertain. Related article

6/24/20 New York City is experiencing a “surge” in shootings, with “more than double” during a recent three-week period compared with 2019. According to the NYPD data portal, murders are up by twenty-five percent, with 159 this year thru 6/14/20 (last year there were 127 during this period.) Shootings are also reportedly up elsewhere, including Chicago and Minneapolis.

12/6/19 Low-income New York City neighborhoods have seen a rise in gang shootings. One Queens neighborhood has suffered thirty-two shot and twelve killed to date, twice last year’s toll. Special police teams patrol hot spots, and “neighborhood coordination officers” are contacting youth to prevent what violence they can. But guns are cheap and plentiful, and the warfare continues.

12/4/19 During the last four decades wage growth in major cities, including New York and Los Angeles, has stagnated for the lower classes while, thanks to the new technologies, zoomed upwards for the better-off. That, according to New York’s Federal Reserve Bank, has made New York City one of the “top 10 most unequal metropolitan areas in the country.”

10/13/19 A shooting at an unsanctioned “social club” in Brooklyn’s economically-challenged Crown Heights neighborhood (poverty level 24.3 pct.) left four dead and three wounded. A July shooting in Brooklyn killed one and wounded eleven. Patrolled by NYPD’s 77th. Precinct, Crown Heights has experienced an increase in murder, from one to date in 2018 to nine so far this year.

10/4/18 Murders in most of New York City are down, but in a few neighborhoods they’re up. Gun killings in Brooklyn’s poverty-stricken Brownsville area went from seven to date in 2017 (36 wounded) to thirteen this year (47 wounded). A sixteen-year old black youth was the most recent victim. His alleged killer, also black, is only fourteen.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

The Usual Victims Turning Cops Into Liars Place Matters Human Renewal

Repeat After Us: “City” is Meaningless Two Sides of the Same Coin Mission Impossible

Police Slowdowns I Why do Cops Lie? Be Careful (II) Is Crime Up or Down?

Location, Location, Location Role Reversal Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy Cooking the Books

An Inconvenient Truth Liars Figure Too Much of a Good Thing?

|