|

Posted 12/3/19

DID THE TIMES SCAPEGOAT L.A.’S FINEST? (PART II)

Quit blaming police racism for lopsided outcomes. And fix those neighborhoods!

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Part I challenged the L.A. Times’ apparent conclusion that race and ethnicity drove officer decision-making practices during LAPD’s stop-and-frisk campaign. Let’s explore who got stopped and who got searched in greater detail.

Who got stopped?

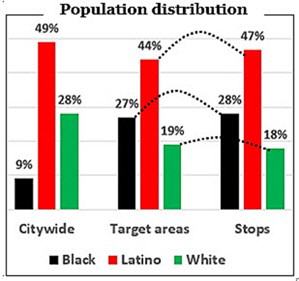

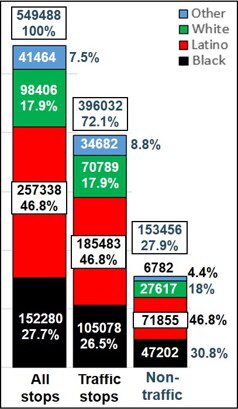

L.A. City is twenty-eight percent white. Yet as the Times noted, only eighteen percent of the 549,488 persons stopped during a ten-month period were white. On the other hand, Blacks, who comprise a mere nine percent of the city’s total population, figured in twenty-seven percent of stops. Proof positive of bias, right?

Not so fast. L.A.’s communities are far from integrated. We coded a random sample of stops for location and identified 52 distinct neighborhoods. Armed with demographics, we compared again. Check out those dotted lines. Once location is factored in, the racial/ethnic makeup of those who were stopped closely corresponds with the demographics of the place where they were stopped. That’s what one would expect. Not so fast. L.A.’s communities are far from integrated. We coded a random sample of stops for location and identified 52 distinct neighborhoods. Armed with demographics, we compared again. Check out those dotted lines. Once location is factored in, the racial/ethnic makeup of those who were stopped closely corresponds with the demographics of the place where they were stopped. That’s what one would expect.

Still, that doesn’t prove that bias didn’t play a role in targeting. For more insight about officer decisionmaking we focused on two data fields pertinent to the “why’s” of a stop: “traffic violation CJIS offense code” and “suspicion CJIS offense code.” (For a list of these Federally-standardized codes click here.) Seventy-two percent of those stopped (n=396,032) were detained in connection with a traffic violation. Overall, the racial/ethnic distribution of this subset was virtually identical to that of the target area. We collapsed the ten most frequent violations into five categories. This graphic displays shares for each racial/ethnic group:

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

Twenty-eight percent of stops (n=153,456) were for non-traffic reasons. Of these, 82 percent (n=126,005) bore a CJIS crime suspicion code. Here are the top five:

The remaining eighteen percent of non-traffic stops lacked a CJIS suspicion code. That subset was 29.5 percent Black, 48.9 percent Latino and 17.4 percent white, which closely resembles the racial/ethnic distribution of target areas.

Proportionately, the distribution of stops – traffic and otherwise – roughly corresponded with each racial/ethnic group’s share of the population. But there were exceptions. Whites were frequently dinged for moving violations and yakking on cell phones, and Latinos for obstructed windows and inoperative lighting. Most importantly, Blacks had an oversupply of license plate and registration issues, with implications that we’ll address later.

Who got searched?

Ninety-seven percent of searches (n=135,733) were of Blacks, Latinos or whites. Justification codes appear in the “basis for search” field. While the CJIS offense and suspicion fields carry a single entry, basis for search is populated with a dizzying variety of comma-delimited combinations (e.g., “1, 4, 5, 12”):

1 – Consent search

2 & 5 – Officer safety pat-down

3 – Presence during a search warrant

4 – Subject on probation or parole

6 – Drugs, paraphernalia, alcohol

7 – Odor of drugs or alcohol

8 – Canine detected drugs

9 & 10 – Search incident to arrest

11 – Miscellaneous

12 – Vehicle impound

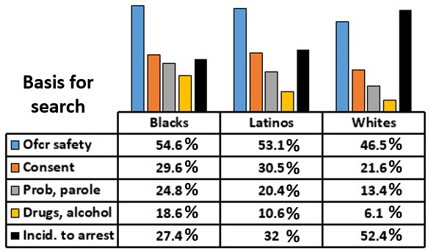

We collapsed the most frequently-used codes into five categories: officer safety, consent, probation/parole, drugs and alcohol, and incident to arrest (percentages exceed 100 because multiple codes were often used.) We collapsed the most frequently-used codes into five categories: officer safety, consent, probation/parole, drugs and alcohol, and incident to arrest (percentages exceed 100 because multiple codes were often used.)

Officer safety was the primary reason cited for searching Blacks and Latinos. When it came to whites, incident to arrest took first place. That may be because whites were substantially less likely than Blacks or Latinos to grant consent, have drugs or alcohol in plain view or be under official supervision.

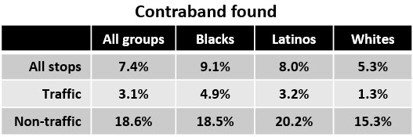

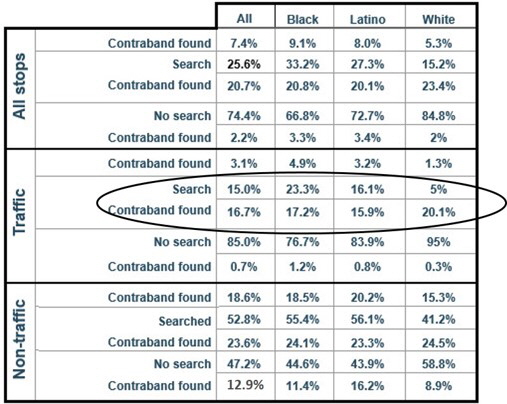

Patterns between groups seemed otherwise consistent, and what differences exist could be attributed to place and economics. Yet a niggling problem persists. Why, as the Times complains, were whites searched far less frequently during traffic stops than Blacks or Latinos? After all, when searched, whites had more contraband! Patterns between groups seemed otherwise consistent, and what differences exist could be attributed to place and economics. Yet a niggling problem persists. Why, as the Times complains, were whites searched far less frequently during traffic stops than Blacks or Latinos? After all, when searched, whites had more contraband!

We’ll get to that in a moment. But first we’d like to point out a couple things that the Times left out. First, only fifteen percent of traffic stops involved a search. When all traffic stops are taken into account contraband was seized – much, assumedly in plain view – from 4.9 percent of Blacks, 3.2 percent of Latinos and 1.3 percent of Whites. We’ll get to that in a moment. But first we’d like to point out a couple things that the Times left out. First, only fifteen percent of traffic stops involved a search. When all traffic stops are taken into account contraband was seized – much, assumedly in plain view – from 4.9 percent of Blacks, 3.2 percent of Latinos and 1.3 percent of Whites.

Neither did the Times say anything about the kinds of contraband seized. Since LAPD’s goal was to tamp down violence, we selected all encounters, traffic or not, where “contraband_type” includes the numeral “2”, meaning a firearm. Overall, 3,060 of the 549,488 individuals stopped during the project (0.06 percent) had a gun or were present when a gun was found. Whites were substantially less likely than Blacks or Latinos to be found with a gun, and particularly when searched.

Back to traffic stops with a search. For this subset the top codes were the same, excepting that parking infractions replaced cellphone misuse. Here are the results:

When we examined all traffic stops the one disparity that caught the eye was a substantial over-representation of Blacks for license plate and registration violations. As the above graphic illustrates, that’s even more so for traffic stops that led to a search. Overall, license plate and registration issues were the most frequent traffic violations linked to a search, appearing in one out of every three episodes (19,789/59,421).

What’s the takeaway?

First, not all stops are created equal. Non-traffic stops are often precipitated by observations – say, a gangster with bulging pockets – that may “automatically” justify a “Terry” stop-and-frisk. Discerning what’s going on inside a vehicle is far trickier. Without something more, ordinary moving violations (e.g., speeding or running a stop sign) and equipment boo-boos (e.g., inoperative tail lights) don’t give an excuse to search.

That “more” can be a registration or licensing issue. If a plate has expired or is on the wrong vehicle, or if a vehicle’s operator lacks a valid license, officers have an opening to parlay a stop into something else. Indeed, a 2002 California Supreme Court decision (In re Arturo D.) expressly endorsed intrusive searches for driver license and vehicle registration information. (In time, the enthusiastic response apparently backfired, and just days ago California’s justices literally slammed on the brakes. See People v. Lopez.) In any event, it often really is about money. Registration and licensing issues are tied to economics, making many Blacks vulnerable to inquisitions while lots of whites get a free pass.

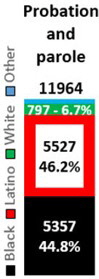

Our analysis of the “basis for search” and “basis for search narrative” fields revealed that at least 11,964 of the 549,488 persons in the dataset were on probation or parole. More than half (6,810, 56.9 percent) were encountered during a traffic stop. It’s not surprising that every last one was searched. Blacks, whose share of persons under supervision (30 percent of probationers; 38 percent of parolees) is about three times their proportion of the population (12.3 percent) were, as a group, by far the most exposed. Our analysis of the “basis for search” and “basis for search narrative” fields revealed that at least 11,964 of the 549,488 persons in the dataset were on probation or parole. More than half (6,810, 56.9 percent) were encountered during a traffic stop. It’s not surprising that every last one was searched. Blacks, whose share of persons under supervision (30 percent of probationers; 38 percent of parolees) is about three times their proportion of the population (12.3 percent) were, as a group, by far the most exposed.

Policing is a complex enterprise, rife with risk and uncertainty. As with other human services, its practice is unavoidably imprecise. Although we’re reluctant to be too hard on our media friends, this may be a good time to remind the Times that trying to “explain” dissimilar outcomes by jumping to the usual conclusion – essentially, that cops are racists – can do a major disservice. As we’ve pointed out in a series of posts (be sure to check out our “stop and frisk” section), when cops target high-crime areas, the socioeconomics of urban America virtually assure disparate results.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

So should police abandon aggressive crime-fighting strategies? That debate has been going on for a very long time. In our view, the real fix calls for a lot more than guns and badges. (For the latest, supposedly most “scientific” incarnation of targeted policing check out “Understanding and Responding to Crime and Disorder Hot Spots,” available here.) In our own, very measly opinion what’s really needed is a “Marshall Plan” for America’s neighborhoods, so that everyone regardless of ethnicity, skin color or financial resources gets the chance to prosper.

Of course, we all know that. Still, we’re waiting for a candidate to utter that magic word. Psst…once again, it’s “neighborhoods”!

UPDATES (scroll)

6/15/24 Dominic Choi, LAPD’s interim chief, feels that traffic stops are a key tool in the fight against violent crime. Some transportation safety experts feel there’s a pressing need to “crack down” on reckless driving. But concerns about racially disparate policing have led the L.A. City Council to assess whether, and to what extent, civilians could take over traffic enforcement and accident investigation, and if stops should be altogether prohibited for minor infractions, such as expired license plates.

12/20/23 A Black Lives Matter lawsuit argues that LAPD patrol officers disproportionately target minorities when deciding that vehicles they encounter may be stolen. Those decisions lead to highly choreographed, force-rich responses that involve pointing guns and having citizens lie face down on the ground. Most of the vehicles, though, turn out not to be stolen. Yet many innocents are nonetheless traumatized.

12/21/22 Statistics that show Black motorists are stopped at a rate more than twice their share of the population has led California legislators to introduce a bill that prohibist “pretextual stops.” Officers could not stop drivers for only non-traffic safety reasons, such as “license plates, lighting or vehicle registration.” Officers concede they do so to find evidence of crime. But critics contend that seldom happens.

11/28/22 According to a new report by the National Registry on Exonerations, innocent Black persons are approx. “seven-and-a-half times more likely to be convicted of murder” than innocent Whites. Contributing to the disparity is the far higher rate of murder in areas populated by Black persons. Innocent Blacks are also more than eight times more likely than innocent Whites to be convicted of rape. And because “racial profiling” leads them to be stopped far more often, innocent Black persons are also disproportionately convicted of drug crimes.

11/15/22 In March a new rule prohibited LAPD officers from making traffic stops unless the observed violation “significantly interferes with public safety.” That rules out “pretextual” stops that use minor infractions to justify stopping persons on a mere hunch that they are criminals. A Los Angeles Times review indicates that the number of such stops has indeed plunged. Seizure of illegal items is also down, with 374 fewer guns recovered during the five months following the rule’s enactment than during a comparable period the preceding year.

3/2/22 A numerical analysis of stops by Chicago police between October 2017 and February 2020 revealed that they took place more frequently in higher-crime Districts. Black persons where disproportionately stopped for investigative reasons in all areas of the city regardless of their share in the population. This also held true for traffic stops except in two Districts where the Black share of the population is very large. Neither White nor Hispanic persons were disproportionately stopped across the city. Officer reasons for the stops were not analyzed. Report

2/26/22 L.A.’s Police Commission is expected to approve a rule that requires officers to have a clearly articulable reason for using a traffic violation as a pretext for stopping motorists. Stops “should not be based on a mere hunch or on generalized characteristics such as a person’s race, gender, age, homeless circumstance, or presence in a high-crime location.” Officers would be required to speak that reason into their body recorders before or during the stop. Police unions strongly object to the proposal. So do civil libertarians, who call it a “sham” that would let cops keep discriminating against persons of color.

8/28/21 L.A. Council members and community activists are complaining about delays in developing a plan to replace police officers with civilian traffic enforcement agents. Spurred by complaints that police use traffic laws as pretexts to stop minority motorists, the study, which is expected to take up to one year to complete, will be conducted by a contractor whom the city now promises to select by November.

5/25/21 In 2020 murders in L.A. surged 36 percent, reaching a decade-high 305. Police Chief Michel Moore attributes the spike to gang violence, the “despair and dislocation” of COVID, and the elimination of cash bail, which quickly put violent persons back on the streets: “When those gun arrests are not going to court...zero bail, court trials being deferred...there’s a sense [of] a lack of consequences.” Defunding the police has been replaced by a drive to replenish the ranks. Stop-and-frisk, once abandoned, is back in South L.A., where an elite unit is waging a targeted campaign.

2/13/21 A surge in shootings and murders has led LAPD to redeploy uniformed “Metro” teams to conduct investigative stops in affected areas. According to Chief Michel Moore, officers are “held to a high standard” and only act when there is “reasonable suspicion” or “probable cause.” So far officers have made 74 stops, arrested fifty and seized 38 guns. But libertarians worry that abuses are inevitable. Note: Chief Moore later corrected the number stopped to 639, which he said is still far less than the 2,400 stops per month Metro conducted in 2019.

10/24/20 According to the L.A. Times, a new LAPD Inspector General report about stops in 2019 notes, among other things, “that units specifically assigned to suppress crime made more stops in high-crime areas in communities of color, and were more likely to subject the people they stopped to extensive questioning — about their backgrounds, their parole or probation status and their criminal records — and to other tactics, such as handcuffing, forcing them to face a wall or checking tattoos.”

7/28/20 LAPD’s “Community Safety Partnership,” an intensive community-building effort that fields 100 officers in nine inner-city neighborhoods, is being expanded into an agency-wide bureau with its own deputy chief. Its move is being criticized by protest groups as insufficient and fundamentally misdirected: “This is not a program that needs to be operated by armed, sworn police officers.”

7/10/20 A massive criminal complaint charges three officers in LAPD’s Metro unit with falsifying official records by falsely claiming that persons they had stopped were gang members or associates.

6/25/20 Activists are challenging why California’s Cal Gangs database, which police consult to determine whether someone is a gang member, has yet to comply with an audit that required a purge of erroneous entries. While the state refuses to make changes that would shrink the database and tighten the process of adding names, “to strengthen community trust” LAPD decided to forego its use altogether.

6/4/20 A New York Times review of several years of Minneapolis PD use of force data concluded that officers used force on blacks seven times more frequently than on whites. Although the tone of the piece was highly critical, its writers conceded that most of the incidents occurred in higher crime areas where more blacks live. Blacks were also subject to more police force elsewhere, but its frequency was small.

6/4/20 L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that LAPD officers will be prohibited from adding more names to Cal Gangs, the statewide gang database. His move came in response to protests about the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police.

1/9/20 A number of LAPD officers (reportedly, more than a dozen) assigned to its stop-and-frisk campaign have been removed from duty for purposely and incorrectly portraying persons they stopped as gang members, thus inflating their productivity and minimizing errors. NY Times

1/5/20 An official analysis of RIPA vehicle and pedestrian stops by California’s eight largest law enforcement agencies during the second half of 2018 revealed similar racial/ethnic patterns to what was reported for Los Angeles. Blacks (and Native Americans) were the most frequently arrested. Blacks were also searched nearly three times as often as whites although the latter were more frequently found with contraband. There was no racial/ethnic breakdown for being on probation or parole, nor for having firearms.

12/4/19 Oregon’s Supreme Court banned officers from going off-topic during routine traffic stops and questioning occupants about unrelated matters. In this case an officer who pulled over a car for failure to signal a turn asked for and received consent to search the vehicle, in which he found drugs. Decision

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED REPORTS

Los Angeles stops Statewide stops

RELATED POSTS

Special topics: Stop-and-frisk Neighborhoods

Good News/Bad News Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (I) (II) Does Race Drive Policing?

Full Stop Ahead Cop? Terrorist? Both? Fix Those Neighborhoods! RIP Proactive Policing?

Should Police Treat the Whole Patient? A Conflicted Mission Can the Urban Ship be Steered?

A Recipe for Disaster Driven to Fail Police Slowdowns (II) Is it Always About Race? Traffic Stops

Posted 11/12/19

DID THE TIMES SCAPEGOAT L.A.’S FINEST? (PART I)

Accusations of biased policing derail a stop-and-frisk campaign

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Let’s begin with a bit of self-plagiarism. Here’s an extract from “Driven to Fail”:

As long as crime, poverty, race and ethnicity remain locked in their embrace, residents of our urban laboratories will disproportionately suffer the effects of even the best-intentioned “data-driven” [police] strategies, causing phenomenal levels of offense and imperiling the relationships on which humane and, yes, effective policing ultimately rests.

Our observation was prompted by public reaction to the collateral damage – the “false positives” – when specialized LAPD teams cranked up the heat in high-crime areas. Stripping away the management rhetoric, L.A.’s finest embarked on a stop-and-frisk campaign, and we know full well where those can lead. Facing a citizen revolt, LAPD promised to fine-tune things so that honest citizens would be far less likely to be stopped by suspicious, aggressive cops.

Well, that was in March. Seven months later, the Los Angeles Times reported that while the number of stops did go down, substantial inequities persisted. Among other things, blacks were being stopped at a rate far higher than their share of the population (27% v. 9%), while whites benefitted from the opposite tack (18% v. 28%). What’s more, even though whites were more likely to be found with contraband, they were being searched substantially less often than Blacks and Latinos.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

That, indeed, was the story’s headline (“LAPD searches blacks and Latinos more. But they’re less likely to have contraband than whites.”) And the reaction was swift. Less than a week later, Chief Michel Moore announced that his specialized teams would stop with the stop-and-frisks and shift their emphasis to tracking down wanted persons:

Is the antidote or the treatment itself causing more harm to trust than whatever small or incremental reduction you may be seeing in violence? And even though we’re recovering hundreds more guns, and those firearms represent real weapons and dangers to a community, what are we doing to the tens of thousands of people that live in those communities and their perception of law enforcement?

To be sure, policing is an inherently “imprecise sport,” and doing it vigorously has badly upset police-community relations elsewhere. Still, if the good chief wasn’t just blowing (gun)smoke, foregoing the seizure of “hundreds” of guns might tangibly impact the lives of those “tens of thousands” who live in L.A.’s violence-plagued neighborhoods, and not for the better. (For an enlightening tour of these places check out “Location, Location, Location.”)

To better assess LAPD’s approach we turned – where else? – to numbers. California’s “Racial and Identity Profiling Act of 2015” mandates that law enforcement agencies disseminate information on all stops, including every detention or search, traffic and otherwise, voluntary or not. For its reporting the Times analyzed LAPD stop data for the period of July 1, 2018 through April 30, 2019. It’s available here.

We downloaded the massive dataset and probed it using specialized statistical software. It contains 549,488 entries, one for each person whom officers proactively contacted during that ten-month period. (Actual stops were considerably fewer, as many involved multiple individuals.) About seventy-two percent (396,032) of those contacted were encountered during vehicle stops for traffic violations. The remaining 153,456 were detained outside a vehicle (“non-traffic stops”.) Reasons included on-view offending (e.g. drinking, littering or smoking a joint), openly possessing contraband such as drugs or guns, behaving in a way that suggested the possession of contraband or commission of an offense, having an active warrant, or being a probationer or parolee of current interest. We downloaded the massive dataset and probed it using specialized statistical software. It contains 549,488 entries, one for each person whom officers proactively contacted during that ten-month period. (Actual stops were considerably fewer, as many involved multiple individuals.) About seventy-two percent (396,032) of those contacted were encountered during vehicle stops for traffic violations. The remaining 153,456 were detained outside a vehicle (“non-traffic stops”.) Reasons included on-view offending (e.g. drinking, littering or smoking a joint), openly possessing contraband such as drugs or guns, behaving in a way that suggested the possession of contraband or commission of an offense, having an active warrant, or being a probationer or parolee of current interest.

Latest Census estimates peg L.A. City as 48.7 percent Hispanic/Latino. As the bar graph shows their share of stops came in at 46.8 percent, well in sync with that figure. Yet as the Times alarmingly noted, whites, who comprise 28.4 percent of the city’s population, figured in just 18 percent of stops, while Blacks, whose share of the city’s population is only 8.6 percent, accounted for a vastly disproportionate 28 percent of stops.

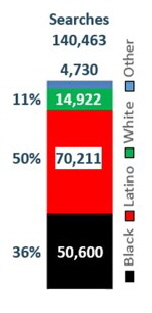

And there was the matter of searches, as well. We crunched the numbers and produced this graph.

As the Times reported, only a measly five percent of traffic stops of whites led to a search. Meanwhile  Latinos were searched in 16.1 percent of traffic stops, and Blacks in 23.3 percent. Yet searches of whites reportedly turned up loot more often. Might whites, as the Times clearly suggests, be getting away with something? Latinos were searched in 16.1 percent of traffic stops, and Blacks in 23.3 percent. Yet searches of whites reportedly turned up loot more often. Might whites, as the Times clearly suggests, be getting away with something?

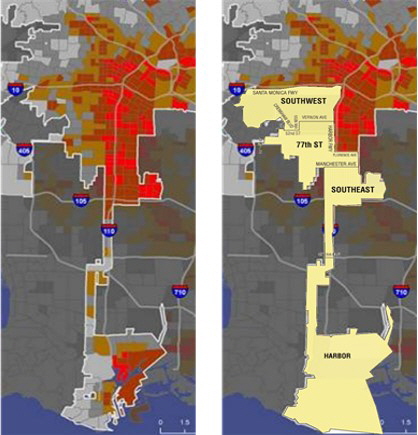

As we discussed in “Driven to Fail,” stop-and-frisks had for better or worse become LAPD’s key tool in a campaign to tamp down violence. Specialized teams focused – albeit, not exclusively – on hot spots called “Laser” zones. A disproportionate number were in South and Central bureaus, the poorest and most severely crime-impacted areas of the city, predominantly populated by Hispanic/Latinos and Blacks.

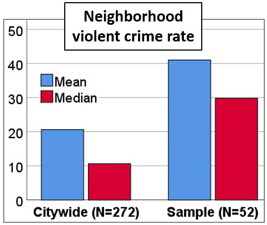

Unfortunately, no stop location is given other than street address. Nor is there any information about crime rates or poverty levels. We set out to fill these gaps. To make the project doable we used statistical software to draw a random sample of one-hundred encounters. Given the dataset’s huge size that’s admittedly too few to adequately represent the whole. But it’s a start.

Our sample includes one-hundred distinct individuals who were detained at one of ninety-nine unique stop locations. Seventy were stopped while in vehicles; thirty not. Overall, their race and ethnicity – 45% Hispanic/Latino, 32% Black, 16% white – came pretty close to the corresponding distribution (46.8%, 27.7%, 17.9%) for the full dataset. So we feel fairly confident extending our findings to the whole.

Let’s talk about the sample. Using the Times’ “Mapping L.A.” utility, which tracks the city’s 272 neighborhoods, we obtained violent crime data for the fifty-two neighborhoods that encompass the ninety-nine distinct street locations where citizens were stopped. It’s apparent from the sample that LAPD targeted the city’s more violent places. As the chart indicates, the mean violent crime rate of the sample’s neighborhoods, 41, is twice the citywide rate of 20.6, while the sample’s median rate, 29.8, is nearly three times the citywide 10.6. Violence rates in 36 of the sample’s 52 neighborhoods exceed the citywide mean, and all but three exceed the citywide median. Let’s talk about the sample. Using the Times’ “Mapping L.A.” utility, which tracks the city’s 272 neighborhoods, we obtained violent crime data for the fifty-two neighborhoods that encompass the ninety-nine distinct street locations where citizens were stopped. It’s apparent from the sample that LAPD targeted the city’s more violent places. As the chart indicates, the mean violent crime rate of the sample’s neighborhoods, 41, is twice the citywide rate of 20.6, while the sample’s median rate, 29.8, is nearly three times the citywide 10.6. Violence rates in 36 of the sample’s 52 neighborhoods exceed the citywide mean, and all but three exceed the citywide median.

Prior posts emphasize the centrality of neighborhoods. What about them might steer its inhabitants down the wrong path? Poverty – and what comes with being poor – are usually at the top of the list. We gathered racial/ethnic composition and poverty level data for each of the sample’s fifty-two stop locations by entering their Zip code into the 2017 American Community Survey. (Incidentally, a quick way to get a Zip code is to type the street address into Google.) This graph displays the results:

No surprise: whites predominate in most of the sample’s economically better-off neighborhoods. As poverty rates increase (note the citywide mean of 20.4 percent) Hispanic/Latinos and Blacks come into the majority. Crime, as this scattergram illustrates, follows a similar pattern.

Each circle represents one of our fifty-two neighborhoods. Clearly, as poverty increases, so does violence. Number crunchers pay attention: the r correlation statistic (zero means no relationship; one is a perfect, lock-step association) is a sizeable .612; what’s more, the two asterisks mean the coefficient (the .612) is statistically significant, with less than one chance in a hundred that it was produced by chance.

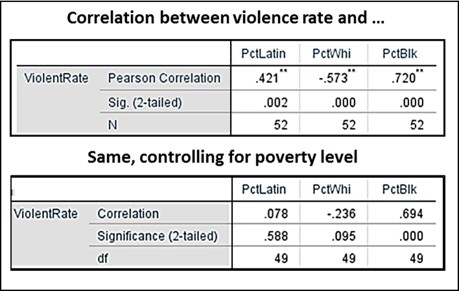

So what happens when we plug in race? This group of scattergrams depicts the “simple” (read: potentially misleading) relationship between each racial/ethnic group and violent crime:

As percent Hispanic/Latino and Black increase so does violence, while as percent white increases, violence falls. But we know full well that violence isn’t “caused” by race or ethnicity. It’s influenced by a variety of factors; for example, family supports, peer influences, childcare, educational, training, job and career opportunities, and so on. Of course, we’d love to assess the impact of each, but things would quickly become unwieldly. Instead, we can turn to poverty as their surrogate. Going back to the 52-neighborhood sample, let’s see whether factoring in (“controlling for”) poverty makes a difference:

|

Sure enough, once poverty is thrown into the mix, the simple (“zero-order”) relationships between race/ethnicity and crime substantially weaken. In fact, the correlations between race/ethnicity and violence for Hispanic/Latinos and for whites recede so far that their significance exceeds .05, the maximum risk that social scientists will take that what seems to be a relationship was produced by chance. What’s more, controlling for poverty is a crude approach. Imagine if one could accurately “control” for the influence of each and every important factor. Might the relationships between race/ethnicity and violence drop to zero?

Of course, neither criminologists nor cops nor ordinary citizens are surprised by the notion that violence is a byproduct of economic conditions. Even under the most sophisticated targeting protocols, police crackdowns usually wind up focused on poor places because that’s where violence takes its worst toll. Alas, as we recently pointed out in “Driven to Fail,” the imprecision of policing – and the behavior of some admittedly imperfect cops – can easily produce a wealth of “false positives,” straining officer-citizen relationships that may already rest on flimsy supports. And leading to outcomes such as what drove us to write this piece.

To be sure, there are “yes, buts.” Check out our (thankfully) final graphic:

Suspicions at the L.A. Times were aroused by the discovery that an unseemly small percentage (17.9) of vehicle stops were of whites. Does that mean that L.A.’s cops are bigots? Well, as we’ve discussed, the targeting protocol zeroed in on 52 areas (right-side graphic) whose proportions of white and black residents differ substantially from their citywide numbers (left-side graphic.) And in the end, the racial/ethnic distributions of those stopped (center graphic) closely approximates that of the right-side graphic, meaning the population officers actually faced.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Yes, but. Maybe cops expressed their bigoted nature in another way. After all, how does one “explain” that only five percent of car stops of whites resulted in a search? (For Latinos it was 16.1 percent; for Blacks, 23.3.) And that more contraband was found when the few, unlucky whites got searched? Might it be, as the Times clearly implies, that in their haste to lock up Blacks and Hispanics L.A.’s finest purposely overlooked far more serious evil-doing by whites?

Well, that’s enough for now. Part II will continue exploring the disparities using data from several obscurely coded fields in the master file. We’ll also have something to say about the types of contraband seized and from whom. (Thanks to the dataset’s unwieldly structure, that takes some doing.) And we’ll probably close off with some inspiring words of wisdom about vigorous policing. But that’s for next time. So stay tuned!

UPDATES (see Scapegoat II)

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED REPORTS

Los Angeles stops Statewide stops

RELATED POSTS

Good News/Bad News Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (I) (II) Does Race Drive Policing?

Full Stop Ahead Cop? Terrorist? Both? Fix Those Neighborhoods! RIP Proactive Policing?

Don’t “Divest” - Invest! But is it Really Satan? A Conflicted Mission Urban Ship

A Recipe for Disaster Scapegoat (II) Human Renewal “City” is Meaningless Mission Impossible?

Two Sides of the Same Coin Driven to Fail Police Slowdowns (I) (II) Too Much of a Good Thing?

Location, Location, Location Is it Always About Race? What Can Cops Really Do?

Of Hot-Spots and Band-Aids

Posted 3/27/19

DRIVEN TO FAIL

Numbers-driven policing can’t help but offend. What are the options?

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. It’s been a decade since DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Assistance kicked off the “Smart Policing Initiative.” Designed to help police departments devise and implement “innovative and evidence-based solutions” to crime and violence, the collaborative effort, since redubbed “Strategies for Policing Innovation” (SPI) boasts seventy-two projects in fifty-seven jurisdictions.

Eleven of these efforts have been assessed. Seven employed variants of “hot spots,” “focused deterrence” and “problem-oriented policing” strategies, which fight crime and violence by using crime and offender data to target places and individuals. The results seem uniformly positive:

- Boston (2009) used specialized teams to address thirteen “chronic” crime locations. Their efforts reportedly reduced violent crime more than seventeen percent.

- Glendale, AZ (2011) targeted prolific offenders and “micro” hot spots. Its approach reduced calls for service up to twenty-seven percent.

- Kansas City (2012) applied a wide range of interventions against certain violence-prone groups (read: gangs). It reported a forty-percent drop in murder and a nineteen percent reduction in shootings.

- New Haven, CT (2011) deployed foot patrols to crime-impacted areas. Affected neighborhoods reported a reduction in violent crime of forty-one percent.

- Philadelphia (2009) also used foot patrols. In addition, it assigned intelligence officers to stay in touch with known offenders. Among the benefits: a thirty-one percent reduction in “violent street felonies.”

- Savannah (2009) focused on violent offenders and hot spots with a mix of probation, parole and police. Their efforts yielded a sixteen percent reduction in violent crime.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

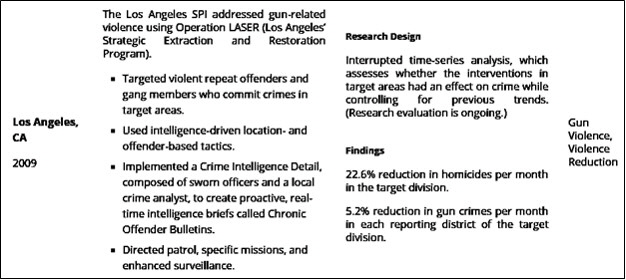

We saved our essay’s inspiration – Los Angeles – for last. It actually boasts three SPI programs. Two – one in 2009 and another in 2014 – are directed at gun violence. A third, launched in 2018, seeks to boost homicide clearances. So far, DOJ has only evaluated the 2009 program. Here is its full SPI entry:

|

From a tactical perspective, the project falls squarely within the hot-spots and focused deterrence models. But its fanciful label – LASER – gave us pause. “Extracting” bad boys and girls to restore the peace and tranquility of hard-hit neighborhoods conjures up visions of the aggressive, red-blooded approach that has repeatedly gotten cops in trouble. Indeed, when LASER kicked-off in 2009 LAPD was still operating under Federal monitoring brought on by the Rodney King beating and the Rampart corruption and misconduct scandal of the nineties. That same year the Kennedy School issued a report about the agency’s progress. Entitled “Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent Decree,” it noted substantial improvements. Yet its authors warned that “the culture of the Department remains aggressive: we saw a lot of force displayed in what seemed to be routine enforcement situations” (pp. 37-38). And that force seemed disproportionately directed at minorities:

A troubling pattern in the use of force is that African Americans, and to a lesser extent Hispanics, are subjects of the use of such force out of proportion to their share of involuntary contacts with the LAPD….Black residents of Los Angeles comprised 22 percent of all individuals stopped by the LAPD between 2004 and 2008, but 31 percent of arrested suspects, 34 percent of individuals involved in a categorical use of force incident, and 43 percent of those who reported an injury in the course of a non-categorical force incident.

During the same period the Los Angeles Police Commission’s Inspector General questioned the department’s response to complaints that officers were selecting blacks and Latinos for especially harsh treatment. In “An Epidemic of Busted Taillights” we noted that members of L.A.’s minority communities had filed numerous grievances over marginal stops involving “no tail lights, cracked windshields, tinted front windows, no front license plate and jaywalking.” Yet as the IG’s second-quarter 2009 report noted, not one of 266 complaints of racial profiling made during the prior fifteen months had been sustained, “by far the greatest such disparity for any category of misconduct.” (Unfortunately, the old IG reports are no longer on the web, so readers will have to trust the contents of our post. However, a May 2017 L.A. Police Commission report noted that LAPD’s internal affairs unit “has never fully substantiated a [single] complaint of biased policing.” See pg. 18.)

Despite concerns about aggressive policing, LASER went forward. LAPD used a two-pronged approach:

- A point system was used to create lists of “chronic offenders.” Demerits were awarded for membership in a gang, being on parole or probation, having arrests for violent crimes, and being involved in “quality” police contacts. These individuals were designated for special attention, ranging from personal contacts to stops and surveillance.

- Analysts used crime maps to identify areas most severely impacted by violence and gunplay. As of December 2018 forty of these hotspots (dubbed LASER “zones”) were scattered among the agency’s four geographical bureaus. These areas got “high visibility” patrol. Businesses, parks and other fixed locations frequently associated with crimes – “anchor points” – were considered for remedies such as eviction, license revocation and “changes in environmental design.”

South Bureau wound up with the most LASER zones. Its area – South Los Angeles – is the city’s poorest region and nearly exclusively populated by minorities. As our opening table demonstrates, it’s also the most severely crime-impacted, with the ten most violent neighborhoods in the city and by far the worst murder rate. When we superimpose South Bureau (yellow area) on LAPD’s hotspots map, its contribution to L.A.’s crime problem is readily evident:

|

LAPD’s IG issued a comprehensive review of LASER and the chronic offender program two weeks ago. Surprise! Its findings are decidedly unenthusiastic. According to the assessment, the comparatively sharp reductions in homicides and violent crime that were glowingly attributed to LASER – these included a near-23 percent monthly reduction in homicides in a geographical police division, and a five-percent-plus monthly reduction in gun crimes in each of its beats – likely reflected incorrect tallies of patrol dosage. Reviewers questioned the rationale of the “chronic offender” program, since as many as half its targets had no record for violent or gun-related crimes. Many of their stops also seemed to lack clear legal cause. (Such concerns led to the offender program’s suspension in August.) While the IG didn’t identify specific instances of wrongdoing, it urged that the department develop guidelines to help officers avoid “unwarranted intrusions” in the future.

Well, no harm done, right? Not exactly. At a public meeting of the Police Commission the day the IG released its report, a “shouting, overflow crowd of about 100 protesters” flaunting “LASER KILLS” signs demanded an immediate end to the LASER and chronic offender programs. A local minister protested “we are not your laboratory to test technology,” while civil libertarians complained that the data behind the initiatives could be distorted by racial bias and lead to discriminatory enforcement against blacks and Latinos. And when LAPD Chief Michael Moore pointed out that his agency had long used data, an audience member replied “yeah, to kill us.” He promised to return with changes.

Chief Moore’s comments were perhaps awkwardly timed. In January the Los Angeles Times reported that officers from a specialized LAPD unit had been stopping black motorists in South Los Angeles at rates more than twice their share of the population. They turned out to be collateral damage from a different data-driven effort to tamp down violence. Faced with criticisms about disparate enforcement, Mayor Eric Garcetti promptly ordered a reset.

It’s not that LAPD officers are looking in the wrong places. South Bureau, as the table and graphics suggest, is a comparatively nightmarish place, with a homicide every three days and a murder rate more than twice the runner-up, Central Bureau, and six times that of West Bureau. And while dosages varied, LAPD fielded LASER and the chronic offender program in each area. Policing, though, is an imprecise sport. Let’s self-plagiarize:

Policing is an imperfect enterprise conducted by fallible humans in unpredictable, often hostile environments. Limited resources, gaps in information, questionable tactics and the personal idiosyncrasies of cops and citizens have conspired to yield horrific outcomes.

As a series of posts have pointed out (see, for example, “Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy, Part II”), stop-and-frisk campaigns and other forms of aggressive policing inevitably create an abundance of “false positives.” As long as crime, poverty, race and ethnicity remain locked in their embrace, residents of our urban laboratories will disproportionately suffer the effects of even the best-intentioned “data-driven” strategies, causing phenomenal levels of offense and imperiling the relationships on which humane and, yes, effective policing ultimately rests.

What happens when citizens bite back? Our recent two-parter, “Police Slowdowns” (see links below) described how police in several cities, including L.A. and Baltimore, reacted when faced with public disapproval. A splendid piece in the New York Times Magazine explains what happened after the Department of Justice’s 2016 slap-down of Baltimore’s beleaguered cops. Struggling in the aftermath of Freddie Gray, the city’s finest slammed on the brakes. That too didn’t go over well. At a recent public meeting, an inhabitant of one of the city’s poor, violence-plagued neighborhoods wistfully described her recent visit to a well-off area:

The lighting was so bright. People had scooters. They had bikes. They had babies in strollers. And I said: ‘What city is this? This is not Baltimore City.’ Because if you go up to Martin Luther King Boulevard we’re all bolted in our homes, we’re locked down. All any of us want is equal protection.

If citizens reject policing as the authorities choose to deliver it, must they then simply fend for themselves? Well, a Hobson’s choice isn’t how Police Issues prefers to leave things. Part of the solution, we think, lies buried within the same official reproach that provoked the Baltimore officers’ fury. From a recent post, here’s a highly condensed version of what the Feds observed:

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Many supervisors who were inculcated in the era of zero tolerance continue to focus on the raw number of officers’ stops and arrests, rather than more nuanced measures of performance…Many officers believe that the path to promotions and favorable treatment, as well as the best way to avoid discipline, is to increase their number of stops and make arrests for [gun and drug] offenses.

In the brave new world of Compstat, when everything must be reduced to numbers, it may seem na´ve to suggest that cops leave counting behind. Yet in the workplace of policing, what really “counts” can’t always be reduced to numbers. It may be time to dust off those tape recorders and conduct some some richly illuminating interviews. (For an example, one could begin with DOJ’s Baltimore report.) There may be ways to tone down the aspects of policing that cause offense and still keep both law enforcers and the public reasonably safe.

In any event, police are ultimately not the answer to festering social problems. Baltimore – and many, many other cities – are still waiting for that “New Deal” that someone promised a couple years ago. But we said that before.

UPDATES (scroll)

12/4/24 Predictive policing strategies have garnered opposition because of their tendency to concentrate policing in minority neighborhoods. While police overreach remains a concern, a two-day workshop hosted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine explored how person-based and place-based predictive strategies can be tailored to respond to and help prevent crime in highly impacted areas without leading to abuses. According to NIJ Director Nancy La Vigne, “predictive policing is not just about the prediction but about the type of policing that happens after the prediction.”

4/1/22 The officers who searched Breonna Taylor’s apartment were members of a team that was pioneering Louisville PD’s application of the “place network investigations” approach to combating crime in chronically beset areas. That strategy, which grew from academic research, is in use at a handful of cities, including Las Vegas, Dallas, Philadelphia and Tucson. A “holistic” version of “hot spots,” it also derives from the “PIVOT” approach developed and used in Cincinnati. But Louisville has dropped it.

1/1/22 A New York Times investigation concludes that police traffic enforcement is largely driven by the need of cities - particularly, the smaller - for the revenue produced by fines. That money helps fund policing and other expensive public-safety needs. Agencies press officers to enforce traffic violations, and writing tickets plays a major role in performance evaluation. And thus the cycle continues.

2/13/21 A surge in shootings and murders has led LAPD to redeploy uniformed “Metro” teams to conduct investigative stops in affected areas. According to Chief Michel Moore, officers are “held to a high standard” and only act when there is “reasonable suspicion” or “probable cause.” So far officers have made 74 stops, arrested fifty and seized 38 guns. But libertarians worry that abuses are inevitable. Note: Chief Moore later corrected the number stopped to 639, which he said is still far less than the 2,400 stops per month Metro conducted in 2019.

7/10/20 A massive criminal complaint charges three officers in LAPD’s Metro unit with falsifying official records by falsely claiming that persons they had stopped were gang members or associates.

6/25/20 Activists are challenging why California’s Cal Gangs database, which police consult to determine whether someone is a gang member, has yet to comply with an audit that required a purge of erroneous entries. While the state refuses to make changes that would shrink the database and tighten the process of adding names, “to strengthen community trust” LAPD decided to forego its use altogether.

6/4/20 A New York Times review of several years of Minneapolis PD use of force data concluded that officers used force on blacks seven times more frequently than on whites. Although the tone of the piece was highly critical, its writers conceded that most of the incidents occurred in higher crime areas where more blacks live. Blacks were also subject to more police force elsewhere, but its frequency was small.

6/4/20 L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that LAPD officers will be prohibited from adding more names to Cal Gangs, the statewide gang database. His move came in response to protests about the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police.

4/21/20 LAPD Chief Michel Moore said that due to budgetary constraints brought on by the pandemic, the agency’s crime analysts were discontinuing use of PredPol software. Instead, their work will now be driven by the community-oriented SARA approach. But agency critics championed the move as a victory in their battle against the unfair targeting of minority communities.

1/9/20 A number of LAPD officers (reportedly, more than a dozen) assigned to its stop-and-frisk campaign have been removed from duty for purposely and incorrectly portraying persons they stopped as gang members, thus inflating their productivity and minimizing errors. NY Times

11/18/19 “The way it was used is racist.” Presidential contender Michael Bloomberg announced profound regrets for promoting NYPD’s stop-and-frisk campaign while he was the city’s mayor. Bloomberg says only a sliver of those stopped had guns and that the practice - which he claims to have wound down - led to estrangement from the Black and Latino communities.

7/4/19 LAPD touts PredPol, a computerized “predictive policing” strategy that uses past activity to map where crimes are likely to occur. But many agencies now say that it doesn’t tell officers anything new, or that it simply doesn’t work. According to a researcher the software’s effect “is very small...it can be hard to see.”

4/27/19 In the L.A. Times, a brief note about yet another shooting in South Los Angeles, this one resulting in the death of a young woman and the wounding of her young female companion, possibly committed by “men in a white Suburban”.

4/21/19 An LAPD deputy chief said Metro is in South L.A. because of the violence. “We’re not sending Metro to Pacific Palisades or West Valley. Because of where we put them, the stops are going to be blacks and Latinos.” During one evening, his officers stopped 24 cars and two bicycles. Twenty-five of those encountered were black and 10 Latino. Officers issued six tickets, sixteen traffic warnings and filled out 27 field interview cards. “They did not find any guns or drugs and made a handful of arrests...The biggest catch of the day was...the arrest of a black man [stopped for a traffic violation] who was wanted for a commercial burglary.” The next night South L.A. had three shootings, one fatal.

4/13/19 Although Chief Michel Moore insisted that it had helped reduced crime, LAPD discontinued LASER over concerns voiced by the Police Commission and community members that the approach was poorly controlled, inadequately assessed, and unfairly targeted minorities.

4/6/19 LAPD dropped its “chronic offender” program. Data will still be used, but officers will also revert to “old-school tactics” such as offender descriptions and focusing on recent releasees and known offenders. An officer and police union official called data helpful but distracting. “Community policing, he said, is done best when officers learn areas and know who commits the crimes.”

3/28/19 In a new initiative against violence, Baltimore enlisted the Feds to help in “Operation Seven Sentinels,” a month-plus effort to arrest persons wanted for serious crimes. From a list of 400 they arrested 264, including 25 wanted for murder or attempted murder and 86 for assault.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

“Numbers” Rule - Everywhere Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job (I) (II) Massacres, in Slow-Mo

Full Stop Ahead Cop? Terrorist? Both? Should Police Treat the Whole Patient?

Turning Cops Into Liars A Conflicted Mission Can the Urban Ship be Steered? A Recipe for Disaster

Scapegoat (I) (II) A Workplace Without Pity Two Sides of the Same Coin Mission Impossible

A Magnificent Obsession Police Slowdowns (I) (II) A Very Rough Ride Location, Location

Good Guy II Is it Always About Race? An Epidemic of Busted Tail Lights

Too Much of a Good Thing? What Can Cops Really Do? Of Hot-Spots and Band-Aids

Posted 3/4/19, updated 3/19/21

NO SUCH THING AS “FRIENDLY” FIRE

As good guys and bad ramp up their arsenals, the margin of error disappears

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. During the evening hours of December 8 Ian David Long, 28, burst into the “Borderline Bar & Grill,” a busy nightclub in Thousand Oaks, a Los Angeles suburb. He threw smoke bombs into the crowd and unleashed a barrage of more than fifty rounds from a Glock .45 pistol. Twelve patrons were shot dead and one was wounded. Long hid and waited for police. Two officers soon burst in. Long opened fire, striking Ventura County sheriff’s sergeant Ron Helus five times. A sixth and fatal wound, to the heart, was accidentally inflicted by return fire from a highway patrol officer armed with a rifle.

Long legally purchased his gun two years ago. He had enhanced it with a laser sight and high-capacity magazines, the latter illegal in California yet easily obtainable elsewhere. Why he acted may never be known. During the horrific episode the six-year Marine Corps vet (he served in Afghanistan) posted Instagram messages denying any motive other than insanity: “Fact is I had no reason to do it, and I just thought… f***it, life is boring so why not?”

Long would soon bring the incident and his life to a close with a shot to his own head.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

One month later, on February 12, eight NYPD officers responded to a report that a man with a gun forced two employees into the back of a mobile phone store. Among those who rushed to the scene were two detectives who were nearby when the call came.

Detective Brian Simonsen, 42 and his partner, Matthew Gorman, 34, accompanied two beat cops into the premises. Just then the robber, Christopher Ransom, a deeply troubled 27-year old, emerged from the back, flaunting a handgun. A 42-round barrage instantly followed.

Both detectives were wounded; Simonsen, fatally. A beloved veteran cop, he was working on his day off. The 27-year old suspect, a chronic offender, was also wounded. As it turned out, his “gun” was a realistic-looking toy, so only police rounds flew. An accomplice who was outside acting as a lookout fled but was arrested later.

According to the FBI, 455 law enforcement officers were feloniously killed with firearms between 2008 and 2017. Seventy-one percent (323) fell to a handgun. Most common calibers were 9mm. (94), .40 (78) and .45 (36). Twenty-three percent of deaths (104) were caused by high-powered rifles, with calibers .223/5.56 (34) and 7.62 (26) the most frequent.

During the same period 800 other cops were feloniously injured with a firearm. Handguns were implicated in 557 (72%) of the 770 instances where kind of gun was known. Top three handgun calibers were 9 mm. (166), .40 (92) and .45 (80). Rifles caused 142 injuries (18%); top three calibers were 7.62 (60), .223/5.56 (28) and 5.45/5.56 (15).

Firepower and gun availability have grown exponentially during the past decades. Excluding exports, domestic manufacturers produced 1,333,241 semi-automatic handguns in 2008. Of these, about 827,000 were in 9mm. and larger caliber. A decade later, in 2017, a staggering 3,415,582 pistols were produced for domestic consumption. About 2,220,000 were 9mm. caliber and beyond.

With guns so abundant (and so enthusiastically marketed) it’s inevitable that many will wind up in the hands of criminals (click here for a related blog post and here for a longer piece.) In 2017 ATF traced 316,348 firearms, mostly seized by local police. Nine-millimeter pistols were the most frequently recovered, coming in at 84,196 (27% of the total). A more powerful caliber, .40, was second at 38,311. Forty-five caliber took fifth with 24,242, and .357 came in eighth at 9,500. Rifles were close behind. The devastating 5.56mm./.223 duo had 9,359 cumulative recoveries, while the fierce 7.62mm. of AK-fame had 7,145. These weapons are especially problematic, as their super high-speed projectiles create large temporary wound cavities that pulverize nearby organs and rupture blood vessels (click here for a summary and here for a quick course.)

What’s available to counter these threats? Body armor. Its protective qualities are strongly impacted by bullet size, composition and, especially, velocity. Arranged by protective capability, from least to most, here are the most recent Federal standards for ballistic vests:

Adapted from “Selection & Application Guide 0101.06 to Ballistic-Resistant Body Armor,” p. 12.

FMJ: full metal jacket; JHP: jacketed hollow point; S: soft point; RN: round nose

Levels IA, II and IIIA denote increasingly protective (read: bulkier, heavier, hotter) versions of soft body armor. Defeating high-velocity rifle rounds such as the 7.62 or .223 requires the hard armor of levels III and IV, which are unsuitable for patrol.

During 2008-2017 twenty-two officers died from bullets that penetrated their body armor. (Keep in mind that this doesn’t include non-fatal penetrations, which are likely far more frequent, nor fatalities caused by wounds to areas not protected by armor.) Only one penetration death was attributed to a handgun, a so-called 5.7mm. “big boomer” with ballistics similar to high-powered rifles (an example is the FN “Five-seven.”) All other penetration deaths were caused by rifles, with 7.62mm. and 5.56/.223 caliber tied for the top spot at six deaths each.

How protective should armor be? Given the tradeoff between comfort and safety, Level II has probably been the most popular. Here’s what the Feds think:

For armor intended for everyday wear, agencies should, at a minimum, consider purchasing soft body armor that will protect their officers from assaults with their own handguns should they be taken from them during a struggle; Level IIA, II or IIIA as appropriate. (p. 21)

Of course, even the most bullet-resistant body armor can’t protect against wounds to exposed areas. A recent Houston drug raid gone sour left four officers wounded. Two were struck in the neck, one in the shoulder, and one in the face (all fortunately survived.)

Let’s return to our two examples of “friendly fire.” We don’t know whether the Ventura County sergeant was wearing a ballistic vest. But only a cumbersome armor-plated garment could have protected him from the rifle round fired by his colleague. As for the NYPD detectives, neither was wearing armor, so the consequences seem, with the benefit of hindsight, sadly predictable. Here’s how the victim officers’ superiors explained the tragedies:

Ventura County Sheriff Bill Ayub, about the death of Sgt. Helus: “In my view, it was unavoidable. It was just a horrific scene that the two [deputies] encountered inside the bar.”

NYPD Chief Terence Monahan, the agency’s top uniformed officer, about the death of Detective Brian Simonsen: “We talk about the tactics, we talk about incidents that have occurred over the course of the last six months. You want to avoid that crossfire situation. But understand — it’s great to train — everything happens in a second. You’re reacting within seconds and you’re in fear for your life. Your adrenaline is high.”

“Routinely Chaotic” addressed the chaos and confusion that accompany some street encounters. Can it occasionally lead cops to shoot each other? Well, we’re no tactical wizards, but before conceding that such things are inevitable, here are a few ideas for preventing poor outcomes:

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

- As NIJ suggests, everyone should wear body armor that will, at a minimum, stop a projectile discharged by a colleague. That rules out the use of long guns other than during highly coordinated tactical responses.

- After Columbine, delaying (i.e., “surround and call-out”) is out of favor when innocent lives are at stake. Still, responses must not become chaotic. To prevent possibly lethal confusion an early arrival should remain behind to coordinate colleagues as they show up.

- Fire discipline is essential. Even the most impromptu entry team must designate “point” and “cover.” Who will engage, and who will protect those engaging, must be explicit from the start.

- Routinely Chaotic pointed out that “butting in” can prove lethal. Late-arriving officers, including supervisors, must take their cues from cops already on scene.

Of course, it’s not just police lives that are at risk. “Speed Kills” mentioned that innocent citizens are occasionally wounded and killed by misplaced police gunfire. (We distinguish this from purposeful shootings of citizens who turn out to be innocent.) Googling brought up two recent examples. In one, police bullets pierced a wall and killed a six-year old boy in his home. In the other, two bystanders – a 46-year old woman and a twelve-year old boy – were injured by police bullets that were meant for a fleeing suspect.

In our gun-crazed land the threats that citizens pose to cops and to each other, and that cops occasionally pose to innocent citizens and other cops, are ballistically identical. Officers must routinely exercise great care to avoid compounding this intractable dilemma. We’re confident that at least to that extent, Sheriff Ayub and Chief Monahan would certainly agree.

UPDATES (scroll)

6/23/25 Earlier this month Chicago police officer Krystal Rivera was accidentally shot and killed by her partner as they tried to apprehend a man who fled into an apartment. That man, identified as Jaylin Arnold, 27, managed to flee. But he’s just been arrested for a parole violation. Arnold has been twice convicted and imprisoned for being a felon with a gun. He again faces that charge, as guns were found in the apartment he shared with Adrian Rucker, also an ex-con. Arnold’s also been charged with drug crimes; there were drugs in the apartment, and when caught he had eleven bags of suspected crack. (See below update)

6/9/25 Chicago police officer Krystal Rivera and her partner chased a man they thought was armed into an apartment. Inside they encountered a second man, Adrian Rucker, 25. As officer Rivera kept chasing after the first man, Rucker reportedly pointed an AR-15 style pistol at her partner. He responded with a gunshot. Tragically, the partner officer’s bullet struck officer Rivera in the back, inflicting a fatal wound. A four-year CPD veteran, officer Rivera had already seized two guns during that shift. She is the only Chicago police officer killed in the line of duty so far this year. More guns and ammunition were found in the apartment. Rucker, who had six active warrants, faces a host of charges. (See above update)

7/3/21 Ian David Long, the Borderline Bar shooter, reportedly suffered from PTSD brought on by his experiences as a Marine Corps gunner in Afghanistan. He was reportedly haunted by the image of bodies and was obsessed with death and violence. Investigators believe he took revenge at the bar’s “country college night” because fellow students at Cal State Northridge had “disrespected” his military service.

4/24/21 Located in a neighborhood of “neglect” and “entrenched poverty,” a Knoxville high school has lost five students this year to gunfire. It started in January with the shooting death of a football player, and ended on April 12 with the police killing of a 17-year old who was wanted for domestic violence and reportedly fired at officers in a bathroom. During the confusion one officer reportedly wounded another.

3/19/21 A comprehensive review of the Bordeline Bar & Grill incident by Sheriff’s authorities recommends, among other things, that “Tactical teams should be formed from members of the same agency when possible to ensure tactics and communications are consistent.” It also calls for “radio interoperability” between agencies and stresses that an officer must immediately take charge should no supervisor be present.

8/6/20 LAPD officers dispatched to a residence found a suicidal man flaunting scissors. There were other occupants and a Rottweiler. One officer opened fire, possibly at the dog. A round struck a colleague in the wrist, causing minor injuries.

9/30/19 NYPD officer Brian Mulkeen was accidentally shot and killed by other officers after he fired at an armed felon whom he encountered at a crime-ridden housing project in the Bronx. Although overall crime in New York City is down, the area, patrolled by the 47th. Precinct, had ten shootings to date in 2018 but fifteen so far this year.

9/1/19 A male in his 30s armed with a rifle hijacked a mail truck and went on a shooting rampage in the West Texas cities of Odessa and Midland. He killed seven and wounded nineteen, including three officers, before police shot him dead.

3/14/19 NYPD detectives are issued blue police vests but apparently seldom wear them. At present they must only do so when engaged in activities such as making an arrest, and it may be that in rushing in on the call Det. Simonsen and his partner left theirs behind.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED REPORTS

Ventura County Sheriff “2018 Borderline Bar and Grill Mass Shooting Public Safety Response After Action Review”

RELATED POSTS

When Must Cops Shoot? (II) Punishment Isn’t a Cop’s Job Two Sides of the Same Coin Speed Kills

Routinely Chaotic Ban the Damned Things! Three (In?)explicable Shootings Massacre Control

Is it Always About Race? Good Guy, Bad Guy, Black Guy (I) A Matter of Life and Death

Lessons of St. Pete Bigger Guns Oakland: How Could it Happen? What About Body Armor?

Posted 1/14/19

For “When Walls Collide” click here

Posted 1/3/19

COPS AREN’T FREE AGENTS

To improve police practices, look to the workplace

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. How policing gets done clearly matters. Even if it’s mostly done right, do it wrong once and the consequences can haunt a community and the nation for decades. We’ll examine several prominent, science-based approaches to improving police practices, then (saving the best for last!) offer our own, workplace-centric view.

In 2011, not long before budgetary concerns brought down the annual shindig, your blogger sat in the auditorium as Dr. John Laub delivered the welcoming address at the NIJ conference. In his speech the agency’s freshly-minted director introduced a new way to fuse science and practice.

If that doesn’t ring a bell, shame! Have you never heard of “translational” criminology?

If we want to prevent and reduce crime in our communities, we must translate scientific research into policy and practice. Translational criminology aims to break down barriers between basic and applied research by creating a dynamic interface between research and practice. This process is a two-way street — scientists discover new tools and ideas for use in the field and evaluate their impact. In turn, practitioners offer novel observations from the field that in turn stimulates basic investigations.

We’ll come back to the newfangled concept in a moment. But first, let’s take a brief detour. In 1998, as part of the Police Foundation’s “Ideas in American Policing” series, Professor Larry Sherman applied the “evidence-based” concept from the field of medicine to the field of policing:

Evidence-based policing is the use of the best available research on the outcomes of police work to implement guidelines and evaluate agencies, units, and officers. Put more simply, evidence-based policing uses research to guide practice and evaluate practitioners. It uses the best evidence to shape the best practice.

If acting on evidence seems, well, commonsensical, keep in mind that action-directed cops and reflective scientists are probably not a natural mix. But problems have a way of forcing change. Propelled by a series of social crises, some of which police themselves instigated or made worse, and supported by initiatives such as George Mason University’s Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy, evidence-centric research took off.

DOJ promptly jumped in. “Using Research to Move Policing Forward,” an article in the March 2012 NIJ Journal, highlighted the many benefits of “being smart on crime”:

Evidence-based policing leverages the country's investment in police and criminal justice research to help develop, implement and evaluate proactive crime-fighting strategies. It is an approach to controlling crime and disorder that promises to be more effective and less expensive than the traditional response-driven models, which cities can no longer afford.

The Feds also announced a new website, crimesolutions.gov, that would function as a virtual repository of evidence-based criminal justice practices:

CrimeSolutions.gov organizes evidence on what works in criminal justice, juvenile justice and crime victim services in a way designed to help inform program and policy decisions. It is a central resource that policymakers and practitioners can turn to when they need to find an evidence-based program for their community or want to know if a program they are funding has been determined to be effective.

Click here for the complete collection of strategy and tactics essays

CrimeSolutions.gov is more than a bookshelf. It includes an evaluation component, with experts assigning grades on a sliding scale: effective, promising, inconclusive or no effects. To date, they have appraised 80 policing programs, mostly targeted efforts aimed at a specific community, and 11 broader practices. For example, the program “Hot Spots Policing in Lowell, Massachusetts” focused on reducing disorder in high-crime areas by, among other things, increasing misdemeanor arrests and expanding social services. Evaluators found that it reduced disorder and significantly reduced citizen complaints of burglary and robbery. It was rated effective. “Problem-Oriented Policing,” a widespread practice that assesses community problems and tailors a response, was reviewed through a meta-analysis of ten studies. In all, the practice seemed to yield significant reductions in crime and disorder and received the second-best rating, “promising.”

Basing decisions on evidence is all well and good. But how should knowledge be turned into practice? That’s where “translational” comes in. In his address, Dr. Laub defined translational research as “a scientific approach that reaches across disciplines to devise, test and expeditiously implement solutions to pressing problems.” Just like evidence-based science, the translational approach also has its origins in medicine. To assure that end products are responsive to real-world needs, translational researchers and practitioners must collaborate at each step, from defining the issue to devising, implementing and assessing interventions. Involving practitioners allows them to share real-world knowledge with researchers, while involving experts allows them to convey and interpret scholarly findings to practitioners, who might otherwise be forced to rely on secondary sources.

So what’s mising? Neither the evidence-based nor translational approaches offer a template for discovering needs. That’s where a third paradigm, “Sentinel Events,” comes in. Initially described by Dr. Laub as the “organizational accident model,” it got started in aviation, was adopted by medicine, then became a key NIJ initiative (full disclosure: I was recently welcomed into its listserv and appreciate the kindness.) Sentinel researchers are alerted by things gone wrong. Using a structured, science-based approach, actual episodes of police shootings, wrongful convictions and such are examined in depth to discover weaknesses and devise changes “that would lead to greater system reliability and, hence, greater public confidence in the integrity of our criminal justice system.”

Several studies have praised Sentinel’s potential. For example, “A Sentinel Events Approach to Addressing Suicide and Self-Harm in Jail” (2014) concluded that using it to probe violent episodes in correctional facilities can “help to instill a new culture…that better ensures the safety and well-being of those under their custody.” Still, there is an obvious “if.” Sentinel’s success depends on acquiring accurate and complete accounts of what took place. But strangers who pop in with lots of questions after things turn sour might get a cold reception. How to get the real scoop? Here is what our nation’s medical accrediting agency recommends:

- Those who report human errors and at-risk behaviors are NOT punished, so that the organization can learn and make improvements.

- Those responsible for at-risk behaviors are coached, and those committing reckless acts are disciplined fairly and equitably, no matter the outcome of the reckless act.

- Senior leaders, unit leaders, physicians, nurses, and all other staff are held to the same standards.

NIJ’s 2015 guide for conducting sentinel reviews, “Paving the Way: Lessons Learned from Sentinel Events Reviews” emphasizes avoiding blame. And, harking back to translational research, it recommends that to insure an informed judgment review teams include “sharp-end-of-the-stick practitioners with front-line knowledge” and researchers with “one foot in the practice world and one foot in the research world….” (For a 2014 NIJ collection of brief essays about the sentinel approach click here.)

Sentinel drew our attention because Police Issues also works back from real events, admittedly in a far less scientific way. So what is it that we could possibly add? Let’s begin with a little story.

A very long time ago, after completing his coursework at the University at Albany, your blogger turned to the matter of his dissertation. Fortunately, only two years had passed since he had interrupted his career as a Fed, so his memory of the workplace was still vivid. With invaluable support from Hans Toch and Gary Marx, two scholars with deep knowledge of the police environment, he got the job done. The product, “Production and Craftsmanship in Police Narcotics Enforcement,” explored the interaction between “quantity” and “quality,” which has long bedeviled practitioners of the policing craft. (Click here for a journal article based on the dissertation and here for a more chatty piece.)

We need hardly mention which of the two characteristics addressed in the title proved the more dominant. After interviewing and administering instruments to members of drug units at six police departments of varying size, it was apparent that line-level officers struggled to balance the same pressures to make “numbers” that had dogged your blogger and his colleagues. Here’s a typical officer comment about the salience of “numbers”:

It filters down [that superiors] want higher numbers, so inevitably we give them higher numbers. You turn in your monthly report, you’ve got two arrests, they say “you had only two drug arrests”? Now, you may have gotten the two biggest dealers in the State, but they’re still going to complain because you’ve only got two.

Here’s one about the meaning of a “quality case”:

A quality case is a case where you cover all the little aspects. You make sure your reports are descriptive, that they contain all the elements of the offense necessary for prosecution, that the evidence is properly handled....Basically you’re [covering] all the bases that you feel will be necessary to successfully prosecute that case.

And here’s how your blogger reconciled these views:

It may be that a narrow definition of case quality is an adaptation that allows narcotics police to maintain a craftsmanlike image while presenting the smallest possible impediment to production.

Production pressures have had an unending run in the nation’s major police agencies. Bill Bratton brought along number-centric COMPSTAT when he stepped in to manage LAPD. In 2012, three years after Bratton left, CRC Press released “The Crime Numbers Game: Management by Manipulation.” Authored by two John Jay Criminal Justice professors (one, a retired NYPD Captain), the book spilled the beans on Compstat’s corrupting influence. To make things seem hunky-dory, supervisors ordered officers to increase what could be counted, like car stops, while downgrading the severity of crimes (or if possible avoiding taking reports altogether.) Disgruntled cops soon spilled the beans, generating internal inquiries and a slew of damning media accounts. Alas, Compstat had already been adopted by many agencies and praised as a policing wunderkind (for the Police Foundation’s supportive assessment click here.)

Pressures to “make numbers” (or to keep certain numbers down) are well known in industry. But they’re seldom considered in policing. Let’s plagiarize from a recent post:

In every line of work incentives must be carefully managed so that employee “wants” don’t steer the ship. That’s especially true in policing, where the consequences of reckless, hasty or ill-informed decisions can easily prove catastrophic. But we can’t expect officers to toe the line when their agency’s foundation has been compromised by morally unsound practices such as ticket and arrest quotas. This unfortunate but well-known management approach, which is intended to raise “productivity,” once drove an angry New York City cop to secretly tape his superiors…. And consider the seemingly contradictory but equally entrenched practice of downgrading serious crimes – say, by pressuring officers to reclassify aggravated assaults to simple assaults – so that departments can take credit for falling crime rates.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter