|

Posted 11/8/09

WOULD YOU BET YOUR FREEDOM

ON A DOG’S NOSE?

Dog scent evidence comes under fire

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. “Jag” and “James Bond” are bloodhounds. They drool a lot but they’re nice dogs. And if you believe their caregiver, Fort Bend County (Texas) Deputy Sheriff Keith Pikett, they’re also CSI specialists, with a sense of smell so keen and an intellect so refined that, far more than just following a scent, they can match suspects to crime scenes and accurately convey their findings.

Michael Buchanek knows these pooches only too well. One day in March 2006 the retired Texas sheriff’s captain answered his door. It was deputies from his old agency, armed with a search warrant. Buchanek’s neighbor Sally had been found strangled in a field five miles away, and Pikett’s dogs had supposedly followed a scent from the rope used by the killer to Buchanek’s home.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

Using dogs to track scents is old news. Deputy Pikett and other practitioners of “scent lineups” go it one better. They set up cans in a field. One contains something of the suspect’s, say a shirt, while inside the rest are items belonging to others. Dogs are exposed to a scent from the crime scene and then walked around the cans to see if they alert.

Pikett had been running these tests throughout Texas, where his methods were considered good as gold. He did it this time and reported that, yes, a dog alerted on Buchanek’s can. Convinced that their former colleague was a killer, detectives pressed him to come clean. But Buchanek had come clean. He didn’t kill anyone and wasn’t about to falsely confess.

Buchanek went through hell for five months. Luckily for him, police finally found the real murderer, who pled guilty. Victoria County Sheriff Michael O’Connor was unfazed. “We did the right thing, and the wrong person wasn’t convicted.”

A recent report describes Deputy Pikett’s unusual career. A college graduate with an undergraduate degree in chemistry and a master’s in sports science, Pikett became interested in bloodhounds. By the early 1990’s he was volunteering their services to Texas law enforcement agencies, at first for tracking, then for scent lineups. Although he lacked training in dog handling, followed no protocols and made wild claims of accuracy (his dogs were wrong only once in thousands of trials; they could identify scents many years old) his testimony helped win many convictions. Fort Bend County soon swore him in as a deputy. When a 2002 Texas appeals court opinion declared Pikett a bonafide expert his star rose higher. A Houston citizens’ group named Pikett officer of the year.

That niggling little misfire with Buchanek didn’t slow him down. In 2007 he helped Houston police arrest Ronald Curtis for a series of burglaries, and Cedric Johnson and Curvis Bickham for a triple homicide. Curtis spent eight months in jail before the real perpetrator was caught. Johnson was incarcerated sixteen months before he was cleared; Bickham, eight.

Pikett’s error-plagued sniff-a-thon continued. In early 2009 he gave Yoakum County authorities what they needed to arrest Calvin Miller for rape and robbery. When Miller was quickly cleared by DNA Pikett’s reputation finally began to tumble. In June 2009 a judge in Pikett’s own county ruled that his methods were unreliable. Bad news traveled fast, and everyone he wrongly fingered wound up suing Pikett and the agencies that used him.

Pikett isn’t the only cop charlatan who’s touted canines as ID machines. Pennsylvania trooper John Preston testified in more than 100 cases between 1981 and 1984. In 1981 he used a scent lineup to nail Florida murder suspect William Dillon. One year later his dogs linked another Florida man, Wilton Dedge to a rape. Both were convicted at trial. Decades later DNA proved their innocence; by then Dillon had served 27 years, Dedge, 22.

As scent evidence became more popular technology stepped in. Manufactured in California, the STU-100 “scent transfer unit” purports to suck human scent onto a gauze pad that dogs can sniff. This device was used in the investigation of James Ochoa, arrested in a 2005 carjacking after a bloodhound followed a scent from the vehicle to his home. Threatened with a long prison term, Ochoa pled guilty and got two years. Ten months later DNA proved that another person was the real culprit. Ochoa was released and awarded nearly $600,000. The STU-100 figured in the 1998 arrest of Jeffrey Grant for rape (held four months, he was cleared by DNA and awarded $1.7 million), and the 2003 arrest of Josh Connole for a string of arsons (held briefly, he settled for $120,000 after the real perpetrator was caught.)

Trained canines can track scents and detect vapors emitted by drugs and explosives. When the proof is in the pudding -- one either finds dope or a bomb, or not -- false alerts (and they do happen) can’t lead to a miscarriage of justice. But using a handler’s interpretation of their dog’s behavior as evidence is extremely risky. Lacking a scientific underpinning and validated performance standards, scent comparisons and lineups are nothing more than voodoo. Dogs aren’t calibrated instruments. As living things they are subject to many influencers, yet unlike their handlers they can’t be cross-examined. Could they have been affected by subtle, perhaps unintended cues from their handler? Might they simply have alerted in error?

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

In 2007, after spending two years locked up because he couldn’t make bail, Riverside County (Calif.) resident Michael Espalin went on trial for setting twenty-one brushfires. The prosecution’s principal witness, junior college biology instructor Lisa Harvey, testified that her bloodhound Dakota tracked a scent from a charred incendiary device to Espalin’s home. Dakota also supposedly matched Espalin’s scent to fire scene vapors collected with a STU-100. According to Harvey the dog could detect scents eight years old. “I don’t know how [scent] stays around for eight years. I just know that it does.”

Jurors didn’t buy her testimony, hanging 9-3 for acquittal. Harvey wasn’t used at the second trial, and Espalin was found not guilty. Taking a cue from Deputy Pikett’s victims, he’s now suing both Harvey and the authorities. One can only imagine how deeply taxpayers will have to dig into their pockets this time.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Accidentally on Purpose Better Late Than Never (I) (II) State of the Art...Not!

Wrongful and Indefensible False Confessions Don’t Just Happen

Posted 9/20/09

WHAT’S THE D.A. WANT FROM THE SHERIFF?

The DNA lab, of course. Or if he can get it, everything.

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Orange County (Calif.) District Attorney Tony Rackauckas is a great fan of forensics. So much so, in fact, that he’d like to run a lab. Wouldn’t you know it, there’s one next door!

In 2005 Rackauckas got the Board of Supervisors to part with a cool $500,000 so that he could use DNA for property crimes. But rather than going through the Sheriff’s lab he contracted with a private forensics firm to do the work. Why? Apparently the Sheriff insisted on controlling the process, something that Rackauckas wasn’t willing to give up. Only thing is, CODIS, the FBI’s national DNA databank, only accepts profiles from government labs. No problem: Rackauckas entered into an agreement with the Kern County D.A., who runs his own lab, to upload the data.

Two years later, flush with an additional $875,000 in county funds, Rackauckas set up his very own databank. It’s accumulated the DNA profiles of several thousand misdemeanants and gang members served with injunctions. One of a smattering of “rogue” repositories around the country, the standalone database isn’t bound by State and Federal rules that limit DNA collection to persons arrested or convicted of felonies.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

How does Rackauckas get offenders to contribute? Easy -- he “asks.” It’s an offer that many can’t realistically refuse. And now there’s an added inducement: going scot-free! Yes, that’s right. In exchange for $75 and a DNA sample his prosecutors are dismissing non-violent misdemeanors such as petty theft and drug possession. So what if a few cops get “demoralized”? As long as petty violators keep coming, what happens to them down the road seems to be of little public concern.

Just like his counterparts in Kern, Sacramento and Santa Clara counties, Rackauckas wants his own lab, or if not the whole enchilada, at least the sexy part, the DNA. His most recent attempt was in June 2008, while the Sheriff’s Department was reeling from the resignation of disgraced former Sheriff Mike Carona. Proclaiming his office as “the only organization capable of harnessing the vast potential of forensic DNA technology for our community,” he urged Supervisors to place DNA under him.

And he nearly succeeded. Rackauckas’ move was temporarily short-circuited, first, by acting Sheriff Jack Anderson, who pointed out that he wasn’t consulted, then by the new Sheriff, Sandra Hutchens, who was appalled -- appalled -- at the D.A.’s shameless power grab. A transplant from the far more tightly-wound L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, her recollection of the experience is almost touchingly naive:

“I have never experienced anything like it in more than 30 years of law enforcement,” recalled Sheriff Sandra Hutchens, who took over the department in the midst of the battle. “I couldn't get my brain around it, and no one I've spoken with could either.”

But the struggle wasn’t over, not by a long shot. By the time that Hutchens’ outrage hit the papers the Supervisors had thrown Rackauckas a consolation prize, appointing him to a newly created Sheriff’s lab oversight panel. Its two other members are Hutchens and the County Administrative Officer, the latter clearly there as a referee. (Hutchens was so put off by the whole experience that she memorialized it in the official Orange County Sheriff’s Blog.)

Well, why shouldn’t the D.A. run a lab? In 2005 Orange County resident James Ochoa was arrested for carjacking. Ochoa, who had a drug record, was identified by two victims, and a bloodhound also followed a scent from a baseball cap left in the vehicle to his home. But the O.C. Sheriff’s criminalist who processed the cap and other items recovered from the car determined that the DNA wasn’t Ochoa’s. Her report displeased the head of Rackauckas’ DNA program, Deputy D.A. Carmille Hill, who marched into the lab and demanded that Ochoa not be excluded.

Her request was rebuffed. Still, the D.A.’s office wouldn’t drop the charges. Threatened by a judge with a stiff prison term if convicted, Ochoa was unwilling to roll the dice. He pled guilty and got two years. Ten months later the DNA was positively matched to a suspect in another carjacking. Oops! Ochoa got a $550,000 settlement from the cops and $31,700 from the State.

Concerns about such unholy influences prompted a National Academy of Sciences panel to suggest that labs be independent of law enforcement. To their credit, though, accredited labs subscribe to protocols specifically designed to prevent such pressures. But prosecutors who think they’re only there to convict could make enforcing safeguards problematic. Knowing just how unyielding D.A.’s can be when they’re convinced they’re right -- and the Ochoa case is a perfect example -- that’s an uncomfortable prospect.

DNA is also an expensive tool. A recent study of its use in property crimes estimates the average per-case cost of typing and entering profiles as $374 in Orange County, which processes DNA in-house, and $1147 in Los Angeles, which uses an external lab. (Evidence collection costs aren’t included). When there’s a possible hit DNA costs soar, averaging $13,000 per arrest in Los Angeles and nearly $20,000 in Orange County. And that doesn’t include the expense of creating and maintaining a DNA facility, nor of training and certifying investigators and examiners.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

Supervisors have dumped more than one and a third million bucks into Rackauckas’ DNA programs. There’s no indication that their generosity was based on a comprehensive review of Orange County’s criminal justice needs. Maybe a study would demonstrate that a back-room DNA operation is a good idea. But giving someone money because of their political juice never is.

Ah, your blogger forgot. This is Orange County. Never mind.

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

DNA’S DANDY, BUT WHAT ABOUT BODY ARMOR?

As lethal threats to police increase, protection languishes -- but there’s hope

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. It’s no surprise that Boston cops feel a chill. With criminals wielding powerful semi-automatic weapons whose rounds can sail through walls (and, as in an incident last week, pierce a mattress and strike a 12-year old girl watching T.V.) you’ve got to wonder why anyone would be so foolhardy as to pin on a badge.

Commenting on the tragic event, Boston’s commish bemoaned the proliferation of assault rifles, like the one that wounded the child. They are indeed a significant threat. But there are others. In March a parolee used an AK-type rifle to kill two Oakland SWAT officers who burst into the apartment where he was hiding. Police were there because the man had just shot and killed two patrol officers -- with an ordinary pistol.

And it’s not just “real” criminals who we should worry about. Consider the middle-aged Virginia Beach man who, angry over his eviction, opened up with an AK-47 and a MAC pistol, killing two and wounding three before taking his own life. Or the recent massacre in Alabama where a deeply disturbed 28-year old went on a rampage, slaying ten and wounding six. His weapons? A handgun, a shotgun and two assault rifles.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

You’d think that with all the bullets flying around there would be a massive, Federally coordinated effort to improve ballistic protection for police. But you’d be wrong. Compared to the huge bundles of cash that get thrown at DNA, what’s spent on body armor R & D is puny. Firearms lethality has gone through the roof, yet what beat cops wear today -- when they can, if it’s not too hot -- isn’t much different in comfort and protection than what they wore decades ago.

Enough ranting. At the recent NIJ conference your blogger met someone who really knows what he’s talking about. S. Leigh Phoenix (he goes by Leigh) is Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Cornell University. On faculty since 1974, Leigh specializes in composite materials and high performance fabrics. Dr. Phoenix has designed composite overwraps for containers used in the Space Shuttle and space station programs. He’s also been working on ways to measure, predict and enhance the performance of police body armor. If you’re half as interested in keeping cops protected as he is, read on!

An interview with S. Leigh Phoenix, Ph.D.

How does soft body armor work?

When a projectile hits it creates a small pyramid-shaped pocket. Soft armor, which is comprised of many fabric layers, tries to slow down the projectile by pushing back on it at the peak of this pyramid. The best analogy is to a tent, with the central pole representing the projectile. Applying tension to the sides of the tent drives the pole into the ground. As tension on the tent guys increases and the tent’s wall angles become steeper the force on the pole also increases.

What happens when a bullet strikes armor?

When a continuous-weave fabric is struck by a bullet tension waves fan out in all directions along the yarns, traveling at more than ten times the bullet’s speed. Yarn material behind the waves feeds back towards the peak of the pyramid, allowing a relatively deep pocket to form with fairly steep angles (the steeper the better.) Normally the first few fabric layers will be penetrated, which slows down the projectile a bit. It’s the job of the remaining layers to bring it to a full stop.

Yarns used in body armor are more than five times lighter than steel, yet two to three times stronger. They must be very light, stiff and resistant to stretching. These characteristics allow tension waves to travel quickly; they also keep strands from breaking as they’re pulled into the pyramid. Fabrics must also be light, for wearability, and sufficiently flexible to resist crushing and shattering. Some of these factors work against each other, which complicates things.

Why are ceramic plates used?

Fabric works better when the diameter of the impact patch increases. When high velocity bullets with sharp points strike a plate their tips are blunted. Continued contact with the plate causes mushrooming and deposits debris, further reducing the projectile’s velocity. Current ceramic plates are completely sacrificed in the process.

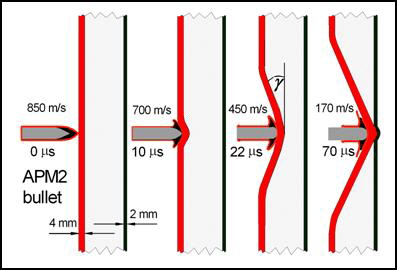

How can we stop high-velocity ammunition?

The diagram depicts a hypothetical approach to stopping an armor-piercing rifle round using a combination of ceramic plates and soft armor. Here the “super” ceramic plate (4 mm. layer) has some flexibility and initially blunts the projectile, causing the lead inside the tip (dark area) to splay out. As the bullet continues its copper jacket slides forward and mushrooms and the interior steel core (large pencil-like region behind the lead) tries to push through, but you want to blunt that too, which takes a little more distance. A final fabric panel brings the slowed projectile to a full stop. This concept illustrates a basic tradeoff: you need distance to stop a projectile, but you don’t want to fill the needed space with heavy materials or the vest will be too heavy to wear. The diagram depicts a hypothetical approach to stopping an armor-piercing rifle round using a combination of ceramic plates and soft armor. Here the “super” ceramic plate (4 mm. layer) has some flexibility and initially blunts the projectile, causing the lead inside the tip (dark area) to splay out. As the bullet continues its copper jacket slides forward and mushrooms and the interior steel core (large pencil-like region behind the lead) tries to push through, but you want to blunt that too, which takes a little more distance. A final fabric panel brings the slowed projectile to a full stop. This concept illustrates a basic tradeoff: you need distance to stop a projectile, but you don’t want to fill the needed space with heavy materials or the vest will be too heavy to wear.

Impressive. But ceramics are hot and heavy. Are there alternatives?

With research and testing it could be possible to develop considerably lighter ceramics that can better withstand the rigors of the job

There’s another approach. At present all ballistic vest yarn is continuous, allowing material to be sent to the impact point. However, the first few layers are usually penetrated, accomplishing little other than some projectile slowing and blunting. It turns out that a single layer of unwoven yarn can be hit at much higher speed without breaking because it’s not loaded down by the drag of all the other yarns around it, especially as the pyramid deepens. In fact, a two or three inch length of the very strongest yarns can be hit at up to 2500 fps without breaking, even with a pointed-tip projectile.

I’ve given thought to using discontinuous yarns -- small segments, say two inches long -- for the first few layers, which instead of snapping would form a wad around the projectile’s nose as it plows through. That would increase the bullet’s frontal area, slowing it down and helping the fabric underneath do its job. Naturally, it would require a lot of development and experimentation to optimize fiber lengths and combinations. Calculations suggest that it could work with velocities in the 2400 fps range, which covers some rifle threats. Otherwise there will be a need for some ceramic, though maybe a lot thinner than what’s now used.

Officers are dying from head shots. What about helmets?

Helmets have a couple of limitations. First, they must float a distance from the skull so there’s room for deflection. They also lack wide, flat surfaces that can be covered with material to pull into the pyramid. So one can’t just take ballistic vest technology and apply it to helmets. But I think that it’s possible to develop a helmet that’s effective against handguns and light enough to wear on patrol.

What’s happened in the last twenty years to improve ballistic protection for police?

Really, not that much. Kevlar has been tweaked, yielding stiffness/strength combinations that marginally improve its velocity performance. A few new fibers have come out. Zylon, which was used on vests and seemed superior, is now on hold due to degradation concerns. Another fiber, M5, potentially much stronger than Kevlar, hasn’t gone commercial because of manufacturing or other problems. Two ultra high-strength polyethylene fibers, Dyneema and Spectra, are 50 percent lighter than Kevlar and just as strong and stiff. They’ve been used in cockpit doors. They may still be too expensive for wide use in vests but perhaps ideal for the helmets mentioned earlier.

Private industry has a big stake in body armor. Can’t we expect them to lead the way?

Body armor makers sell all they produce, so I don’t see major improvements happening under the present commercially-driven system. I know of an example where extensive manufacturing changes could make yarns stronger, but the company isn’t convinced that the investment would pay off financially. Manufacturers also hold their work very close to the chest. They have their own ideas, needs and priorities and collaborating with them is generally difficult, though I’ve been fortunate in one case.

What about Government funding?

Funds from government agencies like NSF and the Army are available if you’ve got the right buzzwords, meaning nanotech, biotech, carbon nanotube structures and so forth, but a lot of what gets proposed and funded is unlikely to lead to useful applications in the near term. Funding systematic work on something practical like body armor is difficult because those making the decisions (who never get shot at) consider the topic old-hat and think that the problems have been addressed and solved, which they certainly have not.

Federal law enforcement research dollars are spread very thin, especially when it comes to academic institutions. DOD concentrates on vehicle armor. Their successes are classified, making them unavailable to university researchers.

Where should we go from here?

A lot could probably be done working with present fiber materials, tweaking them with improved processing to increase their strength without changing the basic chemical structure. You could change how fabrics are designed, say, by developing hybrid layered structures. Coming up with an altogether new material could yield big improvements, but we should not underestimate what clever manipulating can do.

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

To push the frontiers not just as a scientific exercise but with the objective of making significant, practical improvements requires a consortium of knowledgeable, technically-adept researchers who appreciate all the issues, including the need for comfort so that body armor actually gets worn. In other words, one must work on the whole package. We need resources for research and experimentation. We also need an agency or a group of agencies that would host a long-term, comprehensive effort to develop a new materials system that would yield armor that is more protective and comfortable.

Source for figure: S. Phoenix and P. Porwal, “A new membrane model for the ballistic impact response and V50 performance of multi-ply fibrous systems,” International Journal of Solids and Structures (vol. 40, 2003, p. 6724)

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Two Weeks, Four Massacres One Week, Two Massacres Going Ballistic “Friendly Fire”

Ban the Damned Things! Massacre Control A Lost Cause Cops Need More Than Body Armor

Bigger Guns Aren’t Enough

OTHER POSTS IN THE 2009 NIJ CONFERENCE SERIES

Science is Back. No, Really! Ignorance is Not Bliss Slapping Lipstick on the Pig I II III

Posted 2/22/09

N.A.S. TO C.S.I: SHAPE UP!

Putting the “science” back in forensics won’t be simple

For Police Issues by Julius (Jay) Wachtel. Three years in the making, the National Academy of Sciences’ anxiously-awaited “Strengthening Forensic Science in the U.S.: A Path Forward” is finally in, and it doesn’t paint a pretty picture. Although it’s clearly a product of compromise -- the National Institute of Justice reportedly opposed funding the study, then demanded a say in the conclusions -- the report has more than enough meat left on its bones to threaten the interests of labs and self-styled “experts” across the country.

At its most general, the study urges that forensic science live up to its name. Processes used to analyze evidence and make comparisons should be objective, set out in detail, reproducible by others and, as a topper, yield conclusions whose certainty can be accurately estimated, a requirement that places a big question mark next to virtually every identification technique short of DNA. Lamenting the ease with which junk science weasels its way into court, the report’s authors advise establishing a “National Academy of Forensic Science” that would guide research, set standards and certify labs and examiners. To keep unholy influences at bay, they also urge that labs function as independent entities outside the control of both law enforcement and private interests.

Click here for the complete collection of technology & forensics essays

It’s a heady agenda that runs head-on into how forensic science is presently organized in the U.S. While many of the more ambitious objectives stand little chance of being implemented in the near term, the report’s disparaging views on some popular forensic matching techniques will surely be welcomed by the defense bar. Here is some of what Chapter Five, “Descriptions of Some Forensic Science Disciplines” has to say:

- Fingerprint identification. The Grand-daddy of all identification methods comes under criticism, although not for its validity. (That fingerprints are unique between individuals, an assumption based on decades of observation, has apparently gained support from biological science.) Instead, the issue is reliability: does fingerprint comparison yield identical results across examiners? (For a brief depiction of the process click here.)

Crime scene fingerprints are often of poor quality, leading to subjective judgments that occasionally prove wrong. If the error is a false positive (saying that two prints match when they do not) such as what happened in the Brandon Mayfield case, and more recently at the LAPD crime lab, the consequences can be catastrophic. Meanwhile the identification community resists objectivizing its methods; for example, by using point systems based on minutiae, presumably because setting thresholds would yield fewer matches.

When examiners testify that two prints were deposited by the same person they do so to an absolute certainty. Yet, as the report points out, no judgment can be that “certain.” Indeed, it’s the ability to quantify the probability of error that’s the hallmark of a true science. Whether fingerprinting can be raised to that level remains to be seen.

- Shoe prints and tire tracks. Impressions from footwear and tires have “class” characteristics, meaning patterns created during manufacture, and “individual” characteristics, reflecting everyday wear and tear. It’s the latter that are used to match a certain shoe or tire to a certain impression. Like fingerprints, the process is beset by subjectivity and lacks a numerical threshold for calling a match. Unlike fingerprints, it hasn’t been demonstrated that shoe prints and tire tracks are indeed unique, nor that they can be reliably distinguished.

- Toolmarks and firearms. Again, class and individual characteristics are applicable. (For an example of firearms identification click here.) As in shoe prints and tire tracks, issues of subjectivity, “lack of a precisely defined process” and the absence of a threshold for calling a match present significant concerns. In 2008 a Michigan State Police audit revealed that Detroit police experts incorrectly matched guns to ammunition in at least three cases, including one that apparently caused a wrongful conviction. (Detroit PD’s entire lab was shut down and its functions were shifted to the State.)

- Hairs and fibers. Matching hairs through their physical characteristics has been widely used in sex crimes. What the “experts” haven’t been letting on, though, is the abysmal error rate, with two studies citing false positives of about twelve percent, clearly excessive by any standard. These and other shortcomings led the NAS to declare that, lacking nuclear DNA, there is “no scientific support for the use of hair comparisons.”

More hope is held out for comparing fibers, whose chemical composition can be analyzed with existing tools and protocols. However, since little is known about the effects of manufacturing and wear, reliably matching fibers to specific garments or carpets remains out of reach.

- Handwriting. There is some scientific support for the notion that individuals exhibit distinct handwriting characteristics and that these are relatively stable over time. Unfortunately, comparison techniques remain highly subjective, making their validity and reliability difficult to assess.

- Causes of fire. Many arson convictions have relied on expert testimony that pour patterns, charring, glass crazing, etc. were caused by accelerants. But the origin of some of these fires, including one that led to an execution, were later shown to have been accidental. (For a brief discussion click here.) According to the NAS, long-accepted indicia of arson are plagued by poor science and subjectivity. Even so, “despite the paucity of research, some arson investigators continue to make determination about whether or not a particular fire was [deliberately] set.”

- Bite marks. Bite mark evidence is occasionally used in the investigation of violent crime. Although an odontological dissimilarity might help exclude a suspect, the report concludes that the method’s scientific basis is “insufficient” for matching, and warns that its use has led to wrongful convictions.

- Blood spatter. During Phil Spector’s first murder trial a defense expert testified that spatter could reach six feet, potentially placing Spector, whose clothes were flecked with blood, far from the gun (the barrel was in the victim’s mouth when it discharged.) As might be expected, a prosecution witness said that droplets could travel no more than half that distance. (For a brief discussion of the case click here.) Had it been up to the NAS neither witness would have taken the stand. Criticizing the opinions of blood spatter “experts” as overly subjective and driven by advocacy, the report concludes that “the uncertainties associated with bloodstain pattern analysis are enormous.”

What gets admitted into evidence is ultimately up to a judge. Federal practice, on which most State laws are modeled, is set out in Rule 702, Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, “Testimony by Experts.” Before admitting scientific evidence, judges must determine whether “(1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.”

Be sure to check out our homepage and sign up for our newsletter

In the era of C.S.I., with an entrenched forensic establishment that has elevated itself to a near-religion, not even an epidemic of wrongful conviction has managed to slow the choo-choo train of junk science. On the other hand, should defense lawyers take notice of the report, many of today’s quasi-scientific forensic techniques will pass into the realm of voodoo, where they’ve always belonged.

Here’s to their speedy demise.

UPDATES (scroll)

10/24/23 In 2009 the National Academy of Sciences painted a gloomy picture of the forensic art. And a new NAS “feature story” reports that while substantial improvements have been made, pressures “to do things faster, better, and cheaper” can harm the quality of the product. Setting standards helps, but developments such as the digital revolution pose immense challenges. Another critical area, eyewitness identification, also needs attention. Measuring eyewitness cognition and evaluating variables such as lighting are two of the factors under study. 2009 Forensics Report 2014 Eyewitness ID Report

8/2/22 In a research study, 86 active-duty FBI forensic examiners compared 44 sets of handwriting samples that were produced by the same person (“mated”), and 56 that were not. Five responses were possible: “written,” “probably written,” “no conclusion,” “probably not written,” and “not written.” Test subjects assigned “written” to 54% and “probably written” to 34.3% of the mated sets. “Not written” was assigned to 29.6% and “probably not written” to 47.8% of the truly diverging sets. Journal article

1/14/21 DOJ issued a formal rebuttal to criticisms in the President’s Council of Advisors 2016 report that challenged the validity of comparison techniques such as those used by firearms and toolmarks examiners to match firearms to recovered bullets and shell casings. According to DOJ, the report’s conclusions are inaccurate but are being used by courts to exclude worthwhile testimony.

4/9/20 A National Academy of Sciences research article challenges the validity and reliability of an FBI technique that photographically compares markings and imperfections on surfaces such as fabrics. That approach, which has become the specialty of an FBI laboratory scientist, has helped lead to convictions, including of four suspects in a series of robberies and bombings in Spokane.

11/5/19 A New York Times investigation revealed that alcohol breath tests are under challenge across the U.S. Misconduct by operators, faulty technology and ill-maintained, uncalibrated devices are blamed for chronic inaccuracies. In New Jersey, 13,000 drivers were convicted with machines “that hadn’t been properly set up.” Tens of thousands of like cases are pending elsewhere.

|

Did you enjoy this post? Be sure to explore the homepage and topical index!

Home Top Permalink Print/Save Feedback

RELATED POSTS

Accidentally on Purpose Better Late Than Never (I) (II) State of the Art...Not!

Taking the Bite Out of Bite Marks DOJ to Texas One Size Doesn’t Fit All

More Labs Under the Gun Would You Bet Your Freedom...? Forensics Under the Gun

House of Cards

ONLINE VIDEO

“How CSI Went Awry” -- William Thompson, Ph.D., UC Irvine, discusses findings of NAS report and its implications for the future of forensics (71 min.)

RELATED REPORTS

Strengthening Forensic Science in the U.S. Texas Forensic Science Commission - Willingham case

|